Fish and energy movement in Kakadu National Park

Heath Kelsey ·This is the first of a series of blogs intended to begin synthesizing the key messages from Kakadu National Park floodplains research conducted as part of the National Environment Research Programme (NERP). When you put the many pieces together, the story that emerges is all about connections.

The floodplain ecosystem including the rivers, water holes, and billabongs as well as the floodplain itself, requires regular inundation, high energy production, and high quality habitat to sustain important resources. Multiple research efforts are contributing to the developing picture of the connections between the floodplains, water movement, and important natural and cultural resources like fish, turtles, and crocodiles.

Research that helps tell this story includes evaluation of cultural values and use of resources, flood inundation frequency and extent, evaluation of food web energy sources, seasonal movement of fish, sea level rise and salt-water intrusion, and the spread of invasive grasses. These components fit together to illustrate the connectedness of the ecosystem and the important implications that has for management in Kakadu National Park.

Each component is equally important to describe the essential messages from this body of research. A good place to begin is by understanding the connections of fish and the floodplain as a food and energy source. Associate Professor David Crook has been finding some interesting things related to the movements of barramundi (Lates calcarifer) and forktail catfish (Neoarius leptaspis) in Kakadu.

Although information on their movements is limited, these fish were thought to move out onto inundated floodplains during the wet season to take advantage of the seasonally abundant food resources associated with flooding. The barramundi were also thought to migrate from freshwater river systems to coastal and estuarine areas at the beginning of the wet season to spawn, and after spawning had been assumed to spend the bulk of their lives in the ocean and estuary.

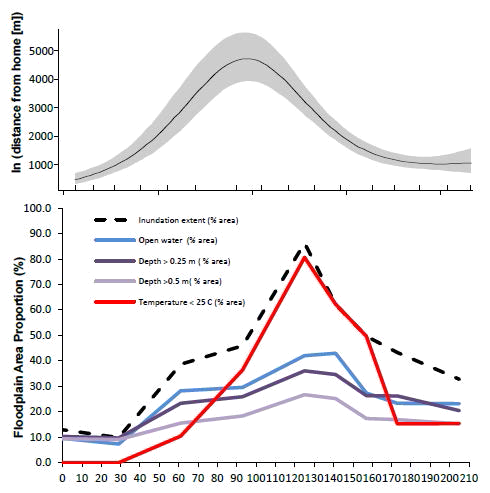

By tracking fish with radio and acoustic transmitters and using listening stations and manual tracking by boat and helicopter, both species were found to move out onto the floodplain as expected, almost immediately when the flood plains became inundated at the beginning of the wet season. At the beginning of the wet season, fish departed their waterhole to take advantage of abundant food on the floodplain and some travelled quite extensively into the estuaries (up to 80 km from home).

Near the end of the wet season, as water quality on the floodplain became poor and emergent plants began to restrict water and fish movement, the fish returned to their home waterhole. The movements of the tagged fish were much more restricted through the dry season, as the waterholes become disconnected and water quality and food sources become limited in the waterholes.

The return of tagged fish to their home waterholes after the wet season mean that the energy derived from food found on the inundated flood plain is returned to the waterhole, allowing these habitats to sustain much larger populations of fish than would be possible without the pulse of energy provided from the floodplain.

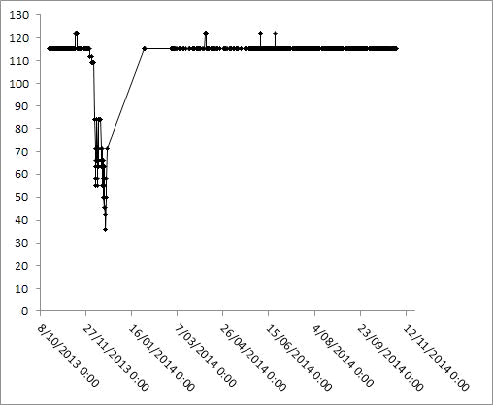

A surprising aspect of the study was that none of the tagged barramundi migrated to the spawning grounds in the saline parts of the estuary in the first year of the study. Very recent downloads of the data have shown that a small number of the tagged fish migrated to the spawning grounds in the second year. These findings suggest that mature fish live in freshwater for several years before migrating downstream to spawn.

Further evidence for this scenario is developed from otolith (a bony structure inside a fish’s ear) research. By looking at the ratio of two Strontium isotopes, researchers can piece together the movements of fish into and out of saline environments.

This is significant in that the transfer of energy via fish migration is dependent on a healthy and regularly inundated floodplain, and on the availability of food and energy on the floodplain. Additional evidence for the importance of energy derived from the floodplain is described in research on food web energy sources, and productivity analysis. Additionally, invasive grasses may interrupt access to and productivity of the floodplain, making it less accessible to the fish, and less energy rich. These additional puzzle pieces will be explored in subsequent blogs.

Reference:

Stuart Bunn, Doug Ward, Brad Pusey, Tim Jardine, Michael Douglas, Erica Garcia, Peter Kyne, Peter Davies, Neil Pettit and Renee Bartolo. 2015. Tropical floodplain food webs connectivity and hotspots; Final report.

About the author

Heath Kelsey

Heath Kelsey has been with IAN since 2009, as a Science Integrator, Program Manager, and as Director since 2019. His work focuses on helping communities become more engaged in socio-environmental decision making. He has over 10-years of experience in stakeholder engagement, environmental and public health assessment, indicator development, and science communication. He has led numerous ecosystem health and socio-environmental health report card projects globally, in Australia, India, the South Pacific, Africa, and throughout the US. Dr. Kelsey received his MSPH (2000) and PhD (2006) from The University of South Carolina Arnold School of Public Health. He is a graduate of St Mary’s College of Maryland (1988). He was also a Peace Corps Volunteer in Papua New Guinea from 1995-1998.

Next Post > Science for Environmental Management 2015 poem

Comments

-

Atika 3 months ago

Thank you for sharing this great information with us, i really appreciate your post!