The Triumph of the Commons: No actually, it can happen!

Rachel Eberius, Krystal Yhap, Suzi Spitzer ·Rachel Eberius, Krystal Yhap, Suzi Spitzer

Man’s tendency to overharvest and exhaust communal goods was first recognized in Garret Harding’s classic 1968 article The Tragedy of the Commons. It is our nature, Harding believed, to act in a rational, self-serving manner and because of this tendency we will inevitably deplete communal environmental resources. In preparation for this week’s discussion, we read the book Sustaining the Commons which provided an alternative perspective to Harding’s Tragedy of the Commons; that, while tragedies of the commons occur, there are many instances of triumphs of the commons where humans are able to self-govern their use of resources. Throughout Sustaining the Commons the authors alluded to design principles identified by Dr. Elinor Ostrom in her book Governing the Commons.

While the text contained a large quantity of material, our class discussion largely focused on 3 topics:

- What are the Commons?

- Examples of Triumphant Commons

- Socio-Normative Dilemmas and the Commons

What are the Commons?

Our dialogue began by clarifying conflicting definitions and uses of the term ‘commons’. The expression originated in Medieval European communities to describe a shared resource with communally developed guidelines for its use. Harding’s ‘commons’ took on a slightly different meaning; an ‘open-access’ resources with no property rights or rules for its use associated. Today we often misuse the term commons based on the definition delivered in Harding’s analogy.

We discussed many examples of open access resources, both natural and manmade –the Chesapeake Bay, Wikipedia, and free WIFI. We concluded that the resources at risk of Harding’s tragedy are those that are subtractable and excludable, because when one individual exploits the resource, other individuals suffer consequences.

Triumphant Commons: We are not all ‘Full-Steam Ahead’ fishermen

So how can the commons be sustainably utilized? Harding theorized that our only options are to privatize land or regulate the use of resources. Must formal institutions intervene in order to successfully manage resource use?

We discussed a small village in Nepal where an atypical practice helps govern the use of irrigation by citizens. If several adults in the village agree that an individual is abusing the system, one of the offender’s cows is confiscated and put into a public ‘cow jail’. If your cow is in ‘cow jail’, the entire community is made aware of your unfair use of water AND the community will milk your cow as payment for the resources you unfairly sequestered.

Is this ‘public humiliation’ tactic plausible for use in the Chesapeake Bay? We decided that ‘cow jail’ is not fundamentally different from being ostracized by the media for environmentally negligent activities. However, being victimized by the media does not (directly) take away your means of survival, as would cow imprisonment.

Another successful commons discussed was the Maine lobster fishery. Though other factors could be involved, much of the fisheries success is attributed to the strict social norms put forth by local communities. In this fishery, as well as many other triumphant commons, one must be immersed in the community in order to learn their unwritten rules and gain acceptance. If you partake in unfair fishing practices, you may find your fishing pots were opened and your catch set free by another member of the community. An interesting feature that was noted in our discussion was the adoption of informal rules into state legislation. Originally a casual practice, reproductive females are marked with a tail notch and thrown back to ensure population growth. This has now been institutionalized by the state government as a law.

Social rules are not to be underestimated. They can entice people to act sustainably, even if it means less personal capital gain.

Socio-Normative Dilemmas and the Commons: We are constrained by things other than our morality

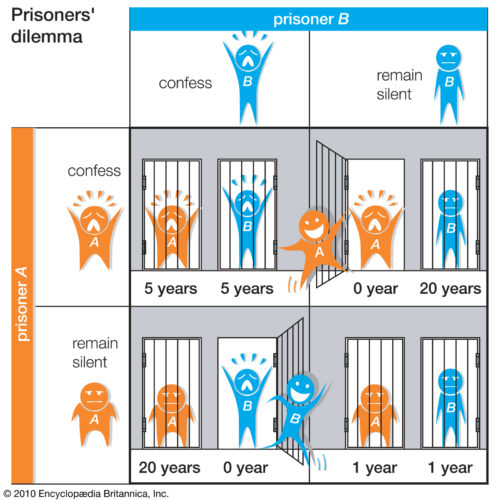

After the (almost) failure of our simulated class fishery in last week’s Fish Banks game, despite my team’s sustainable business tactics, I began questioning the purpose of socially-conscious actions. Can my refraining from certain products or activities really make an impact? This question was posed to the class and the prisoner’s dilemma and free rider problem were reoccurring themes in our discussion.

The basis of these dilemmas is simple; one individual’s selfless actions can and will be exploited by another’s selfish actions. Some argued that after many years of socially-conscious actions one can make a big difference, and it is still worthwhile to act in a socially-responsible way. Others noted that companies respond to the demands of consumers, so if enough people take part we can make a difference. For example, Perdue Farms are producing more organic and hormone free meat because of consumer demand.

However, as a group we still felt that our societal norms and pressures make it difficult to act sustainably. If your cell phone still works, why buy the newest version? If Pennsylvania does not reap any of the benefits of Chesapeake Bay restoration, why should they raise taxes?

One of the most powerful comments made was that 'we are constrained by things other than our morality'. We need certain goods for survival, we want certain goods because of social drivers. Sustainable consumption is hard because 'as a consumer we are weak' and often succumb to pressures other than sustainability.

So what have we learned? The delicate system surrounding an open-access good is complex and difficult to manage. Having a better appreciation for the principles of self-sustained systems is a crucial first step in better managing the commons.

References:

Anderies, J.M., Janssen, M.A. (2013). Sustaining the Commons. Center for Behavior, Institutions and the Environment Arizona State University, ECA 307

Harding, G. (1968). Tragedy of the Commons. American Association for the Advancement of Science: Science. Volume 162; 2242-2248.

Ostrum, E. (2015). Governing the Commons: The Evolution of Institutions for Collective Action. Cambridge University Press. ISBN: 9781107569782

Next Post > Talking ecodrought in Portland, Oregon: food trucks, beer and the Benson Hotel

Comments

-

Rebecca Wenker 7 years ago

I really liked your discussion of being a socially-conscious consumer. I think one of the main reasons it is hard for people to switch to being one is the amount of effort, time, and responsibility you take on when you do so. For example, someone who switches from just eating whatever fish is on display at the supermarket to fish that is harvested sustainably may have to do a lot of additional research to find out where that fish is coming from, how it is treated, etc. This supplementary effort to just choosing what fish to eat is enough for people to not want to deal with.

What helps, like Rachel mentioned, is when a bunch of like-minded people get together to make a difference. If enough people showed interest in where the fish they were eating came from, perhaps the company may make a label for the packaging showcasing their sustainable practices, influencing other fisheries to do the same. This way, those turned off by doing their own research will see it right on the label. So while it may be difficult for one person to make a difference on their own, I think the unity of their ideas with others can be successful.

-

Alec Armstrong 7 years ago

I think it's interesting that we jump from discussions of social groups using common resources (Maine lobster harvesters, Nepalese villagers) to consumers. I think discussions of sustainability are often too fixated on consumers as the wellspring of any solutions to environmental problems. While atomized consumers are often taken as the default economic and environmental agents in our society, it may be important to understand the differences between the aggregated actions of individual consumers and the collective actions of a social group such as a village. Consumers have little power to influence other consumers. Our discussion of the Ostrom notion of the commons emphasized norms and responsibilities, but I do not think the identity of consumer easily takes on this mantle. Ethical consumption is usually defined in opposition to normal consumption, and I think this distinction is easily manipulated into exclusivity - people may be willing to pay more for a product they think sustainable because their act of consumption distinguishes them as enlightened or correct, and companies marketing these products have an incentive to maintain these distinctions, not collapse them.

While consumers have advocates as a group (e.g. Ralph Nader) it seems hard to translate the relationships underlying communities using common resources to this social identity. Consumers are individualized, and the embrace of this identity as the default mode of public social agency in the US may be less a consequence of its efficacy than a reflection of the decline in public or community institutions. I believe voting participation, union membership, fraternal/benevolent society membership, and regular attendance at religious institutions have been declining for decades. I think the commons at risk today (public education, the internet, the climate, innumerable local natural resources) will require changing the norms or responsibilities involved in their use, but as consumers alone we may not be up to this task.

-

Noelle O. 7 years ago

What’s interesting about the lobster gangs of Maine is that tampering with someone else’s traps is illegal, whereas the cow jails might not necessarily be against the law. Also, are Maine lobsters still an open access resource if outsiders are not able to join the fishery easily? I have to admit that I’m a little skeptical about the Maine lobster fishery example, as I don’t think the whole story is presented in the book. I know when fishing regulations were first put in place (minimum and maximum size limits), there was an aggressive push back from the fishermen, even if the fishermen do their own form of policing in order to sustain the resource indefinitely.

I do also agree about consumers being constrained by more than just their morality. For example, luxury, organic or eco-conscious markets like Whole Foods and Trader Joes do not typically exist in rural America. Thus, people may not have money or access to more sustainable produced seafood and produce even if they desired to do so.

-

David Miles 7 years ago

I think the examples we discussed in class about societies and cultures that self regulate is very important in light of today's environmental issues; it should be used as an example of how we can move forward to a sustainable way of living. The point Dr. Hubacek brought up about the "weak consumer" is, in my opinion, very true. Knowing the success cultural/societal pressure can exert, we should leverage this to encourage sustainable practices not only for the consumer, but also for the producers (i.e corporations). Societal pressure may best best way to overcome our inescapable relationship with the dollar. The cow jail example we discussed can and should be a part of this. In a sense, "shaming" corporations and consumers, or in other words, making sustainable practices "cool or trendy" can have much faster and longer lasting effects than passing and enforcing laws and regulations through our increasingly recalcitrant government(in the US anyway). This is not to say that pushing for more regulation or laws should be abandoned, but rather changing society's role in the issue can have a reinforcing effect.

-

Killian F 7 years ago

I also thought the discussion of being a socially-conscious consumer was really interesting. Reading Rebecca’s comment, I was thinking about how the decisions for sustainability and the research for whatever goals the consumer is trying to reach often falls to individuals, but there are some ways society makes these things easier, such as stores that only have products that meet a certain ideal. It also made me think of the example from the readings, where if a lobsterman’s catch didn’t fit the rules, than the buyers that would take the lobsters to market wouldn’t take them from that fisherman. Companies making it easier for consumers to see what is going into the food and products through packaging can also help consumers. This also reminded me of commercials I had seen on TV recently for Perdue chickens, where they were touting how their chickens are antibiotic free. These commercials can help make consumers more aware of what effect their food is having, though it also serves the company since people may be more willing to buy their chickens. Our reading mentioned that there are some large scale problems where voluntary contributions alone are unlikely to solve them, but people shouldn’t take it to mean it is a hopeless cause then, and by working together we should be able to make improvements.

-

Natalie Yee 7 years ago

Great summary! This whole discussion really challenged me to think outside of the daunting notion that every open-access resource will be subject to the tragedy of the commons. This original notion was deeply ingrained in me, and I feel like this discussion opened a lot of possibilities and doors that I would not have thought of. The examples given did tend to be on a smaller scale of commons, making it more easily monitored, but they are still important to recognize and understand that not all commons lead to tragedy.

The discussion about being a socially conscious consumer hit home because it is a struggle that we face on a personal basis. Although the effects of one person on the market does not seem big, there is a big potential that one person's actions make a big difference. It's a slow but meaningful process, and this has lead to greater change.

-

MbS 7 years ago

I love seeing Eiinor Ostrom's photo. She was a friend of Herman Daly, who along with Robert Costanza, pretty much founded ecological economics. Both of them were at UMCP.

Thank you, Rachel and others. What a great course to eavesdrop on via this blog platform.

Greetings from a former IAN-Mees student in science visualization. MbS

-

Krystal Yhap 7 years ago

Rachel did a good job summarizing the ideas of "Sustaining the Commons" that we tried to focus on during our discussion in class. I really like that she touched on the fact that our societal norms sometimes makes it difficult for us to have sustainable consumption. Individuals in society each have a lifestyle they are accustomed to and certain aspects of their lifestyle that they are not willing to give up in order to be considered a sustainable consumer. The weight and value, in terms of importance, that individuals place on shared resources vary and this can make it difficult for groups of people to self-govern shared resources. But what I found the most interesting from Suzi's comment and Rachel's synthesis of our discussion is that there are examples of communities that have been victorious in governing these common resources and a lot of it seems to come back to these social norms and rules that might not be outwardly spoken but are understood by those involved. Even going as far as to have systems of punishment in the form of public humiliation seemed to prove effective in some communities. I think it speaks to the idea of not always needing government regulation and privatization to ensure that a resource is being used and share sustainably.

-

W.Cruz 7 years ago

Great blog! I enjoy the discussion! I found very interesting the sustainable consumer idea. In my opinion people perspective of "need" is based as well in our epistemology but how to change people's minds in terms of what affects the environment and how to improve it? Perhaps education or putting your cow in jail!!

-

Suzanne Spitzer 7 years ago

One example of a “cow jail,” or a means of calling people out for breaking rules and norms of the Chesapeake Bay commons, can be found within the watermen community. We learned that watermen who break rules and harvest in sanctuaries or put their crab pots too close to neighbors’ pots are punished by members of the fishing community. As people in these communities are often friends, family, or neighbors, these punishments often occur in less visible forms than a cow jail in the center of town. For example, a waterman who knows that his brother harvests in protected waters might be less inclined to help him in times of hardship. A crab fisherman whose neighbor continues to inch his crab pots further and further off his own territory and into others’ might find his floating corks cut and his pots lost underwater. These subtle (or not-so-subtle) punishments within the community can help to reinforce norms.

-

V Leitold 7 years ago

I wonder if the ultimate ‘triumph or demise of the commons’ has to do with the scope and scale of the shared resources in question. Most of the examples that we have seen for the sustainable use of the commons involved small communities (e.g., the village in Nepal or the pastures in Switzerland) and/or geographically limited areas (e.g., the Main lobster fishery), where people know each other well and there are long-established social norms (‘unspoken rules’) that all of the members adhere to. In such close-knit communities, “public humiliation” of members who don’t conform to the norms works well as a deterrent because losing one’s reputation in a small community is a high risk to take. I agree with Rachel in that “social rules are not to be underestimated,” and the examples above clearly illustrate the powerful effect of social influences on people’s behavior. However, I wonder if the same kinds of social forces would play out equally successfully if applied to the population of a larger, more dynamic, and much more heterogeneous community (e.g., the city of Baltimore) or society at large. It seems all too easy for people to remain anonymous within those larger groups, enabling ill-intentioned individuals to take unfair advantage of shared resources and not get called out for it if other sanctioning mechanisms are not in place (e.g., meaningful government involvement).

-

Kelly Hondula 7 years ago

Great blog! I enjoyed the discussion of the challenges of sustainable consumption. In class, it was brought up some of the findings from behavioral economics about how knowing how much energy neighbors use can encourage some to use less (http://e360.yale.edu/features/how_data_and_social_pressure_can_reduce_home_energy_use). I think it's interesting that even though there is no "public humiliation" aspect, those companies were able to find a way to exploit social norms and behavioral tendencies to encourage sustainable action.