The Science/Management Gap

Dale Booth, Yuanchao Zhan, A.K. Leight ·The disconnect between science and policy has its root in the concept of the traditional role of scientists in society. The classic view of the scientist is a researcher who is interested purely in pursuing the truth and is without bias or personal stake in the topic at hand. This role makes the researcher completely credible, because they are not swayed by personal values or beliefs. Science and politics therefore are kept strictly separated, with science serving primarily as an information resource for policy makers (Pielke Jr. 2007). This separation however results in the gap between conservation science and implementation. While information may be available in published form, managers often either do not have access to these resources, the training to correctly interpret the results and apply them, or the information does not help inform the choices available to the manager (Fig.1). Roughly two-thirds of conservation assessments fail to deliver effective management actions (Caudron et al. 2012), largely because science and management do not communicate effectively before a project is designed. The result is scientific information that is not useful to the policy makers due to inappropriate content or scales, or lack of inclusion of economic and social context (Arlettaz et al. 2010). In the end, the separation fails to eliminate bias as it was intended, as it is nearly impossible in practice to completely divorce personal beliefs and values from decision making (Jasanoff 1990).

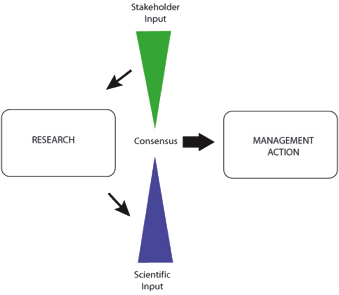

Currently, we are seeing a shift from the classic science paradigm to a stakeholder model that views researchers as taking an active role in decision making and engaging with all invested parties (Fig. 2). When environmental knowledge is generated through collaborations with state agencies, local land owners and researchers, it is much more likely to achieve social acceptance and be relevant to policy decisions (Whitmer et al 2010). As an actively engaged researcher, communication with other stakeholders allows the scientist to shape his/her research in order to answer relevant questions posed by policy makers, and use science to clarify and expand the scope of choices presented to the decision makers (Pielke Jr. 2007).

Academia is structured to favor the old research paradigm, leading to fewer incentives to pursue engaged research. The system rewards researchers who publish in quantity and produce results quickly. Working with multiple partners usually slows down the production process, so researchers are penalized in their careers for pursuing these types of collaborations. There is also no incentive to carry research beyond the knowledge production phase, which means that scientists are not encouraged to put their research into action (Arlettaz 2010). In addition, most research institutions do not encourage the publication of studies in non-peer reviewed journals. This both limits the access of managers to relevant data and slows the distribution of the information as each paper must be put through an exhaustive review process.

Funding institutions should consider taking several measures to encourage engaged research in conservation science. One option would be to call for joint proposals between science and mangers and/or between different disciplines to support early connections between stakeholders. Academic institutions also need to find other metrics for measuring organization prestige beyond bulk academic publications. These metrics could include quantifying the involvement level of outside management agencies and stakeholders, and the production of non-academic papers. Career advancement for researchers should also include factors beyond publication record and incentivize the design and implementation of engaged research projects. We might establish bridging positions within institutions that facilitate communication and collaboration between stakeholders. Finally, academic institutions should establish programs to teach researchers how to communicate with other stakeholders effectively, and think about conservation issues from a cross disciplinary perspective.

References

Arlettaz, R., Schaub, M., Fournier, J., Reichlin, T. S., Sierro, A., Watson, J. E. M., & Braunisch, V. 2010. From publications to public actions: when conservation biologists bridge the gap between research and implementation. BioScience 60(10):835-842

Caudron, A., Vigier, L., & Champigneulle, A. 2012. Developing collaborative research to improve effectiveness in biodiversity conservation practice. Journal of Applied Ecology 49:753-757

Pielke Jr., R. A. (2007). The Honest Broker: Making Sense of Science in Policy and Politics. New York, NY: Cambridge University Press.

Jasanoff, S. (1990). The fifth branch: science advisors as policy-makers. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

Whitmer, A., Ogden, L., Lawton, J., Sturner, P., Groffman, P. M., Schneider, L., Hart, D., Halpern, B., Shlessinger, W., Raciti, S., Bettez, N., Ortega, S., Rustad, L., Pickett, S.T.A., Killilea, M. 2010. The engaged university: providing a platform for research that transforms society. Front Ecol Environ 8(6):314-321

Authors

Dale Booth, Yuanchao Zhan & AK Leight

Next Post > Top ten marine flora symbols: Phytoplankton, macroalgae, mangroves and seagrasses

Comments

-

Bill Nuttle 12 years ago

The stakeholder model is being used in South Florida, where both the Florida Keys National Marine Sanctuary and the Florida DEP Coral Reef Conservation programs are entering a multi-year process to review and update their management plans. Implementation by the Sanctuary is well established, as the Sanctuary was an early adopter of ecosystem planning and the use of marine protected areas in the US. Sanctuary managers rely on committees of stakeholders and science-technical experts for advice and foster interaction between the two groups. California adopted a similar stakeholder-sci/tech pairing of committees to design a revolutionary new approach to marine fisheries management, which relies on establishing a network of marine protected areas.

The advantages and challenges of this new way of employing science in a collaborative "joint fact-finding" was a topic of discussion at the CERF 2011 meeting (c.f.http://cerf2011.blogspot.ca/2011/09/collaborative-decision-making-uses.html).

-

M. Brooks 12 years ago

This topic was a big influence on our post for this week. I am curious about any work done on the tradeoffs between the benefits of the stakeholder model and the time and financial costs, especially in situations when the need for management action is urgent.

-

Miaohua 12 years ago

The two figures is very providential. It let me know the problem between the research and management and how the researcher should consider (stakehold and scitific input). It is educational!