Chesapeake Bay Science and Management: A need for more effective scientific communication and adaptive management

Sabrina Klick, Stephanie Siemek, Wenfei Ni ·Sabrina Klick, Stephanie Siemek, Wenfei Ni

The Chesapeake Bay Program (CBP) was established in 1983 and started the partnership between the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA), the state of Maryland, Pennsylvania, Virginia, and the District of Columbia (NRC 2011). The partnership expanded in 2002 with the addition of Delaware, New York, and West Virginia under the Memorandum of Understanding. The partnership’s initial goal was to reduce nutrient pollution into the Chesapeake Bay by 40% by 2000. The deadline was moved to 2010 when the goal was missed, and then set to 2025 when the deadline was again not reached (Fincham and Strain 2012). With so many states working together, what was keeping CBP from reaching their goal? As pollution was cut back due to multiple efforts, e.g. enforcement of the Clean Air Act (CAA), upgrades of sewage plants and stormwater systems, and improved farming practices, it was found that additional cutbacks were needed.

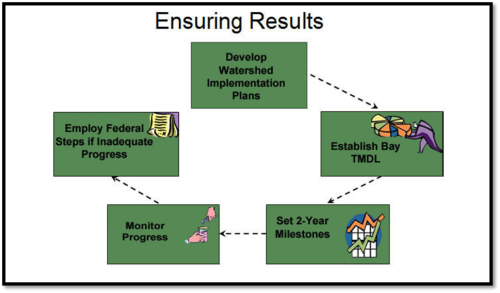

In 2009, the executive order was given to restore the Chesapeake Bay after the release of the 2008 initiatives to increase accountability and transparency of the CBP (NRC 2001). After the deadline to reduce nutrient pollution by 40% was missed for the second time in 2010, two things happened to make the 2025 goal more realistic. First was the establishment of a total maximum daily load (TMDL) by the EPA, which determined maximum loads of nitrogen, phosphorus, and sediment needed to obtain the water quality standards of the Bay by 2025 (NRC 2011). Second, the two-milestone strategy was implemented to focus on increments that could be met by each Bay jurisdiction to meet the new 2025 deadline (Figure 1).

However, the two-year milestone strategy did not identify specific strategies for the Bay jurisdictions to reach the necessary pollution reduction goals. It has been described as a “ladder without rungs” (NRC 2011). Given the history of missed deadlines and unclear strategies regarding restoration of the Chesapeake Bay, it makes one wonder about the water quality status and what has been done differently to reach the 2025 goal.

In the Chesapeake Quarterly of 2012, Michael Fincham suggested that our new slogan should be “we are half way home” because of the previous efforts that have reduced nutrient pollution to slightly over 20%. Also, the seagrasses in the Susquehanna Flats have re-emerged over time (Figure 2) from needed light conditions, absence of storm events, and other ideal plant growth conditions between 1997 and 2002 (Gurbisz and Kemp 2014). The seagrass beds have become more resilient which was seen after Tropical Storm Irene in 2011. A variable correlated to seagrass growth has been river flow where low growth has occurred during periods of wet and high river flow conditions and high growth has occurred during periods of dry and low river flow conditions (Fincham and Strain 2012; Gurbisz and Kemp 2014). The 2013-2014 Bay Barometer has also mentioned the improvement in water quality, increase in seagrasses, rises in abundance of spawning shad and juvenile striped bass, rehabilitated tidal marshes, and the building of six oyster reefs for restoration (Chesapeake Bay Program 2015).

![Figure 2. Shows the increase in submerged aquatic vegetation (SAV) coverage in the Susquehanna Flats over time from 1984 to 2010. The years 2005-2010 show regions of 70-100% SAV coverage (Gurbisz and Kemp 2014 [pdf]). Figure 2. Shows the increase in submerged aquatic vegetation (SAV) coverage in the Susquehanna Flats over time from 1984 to 2010. The years 2005-2010 show regions of 70-100% SAV coverage (Gurbisz and Kemp 2014).](/site/assets/files/2438/figure2-500x347.png)

Citizen science has shown to be successful by the Chester Tester Program which can act as a model program to build citizen science programs in other river systems to improve monitoring efforts. The Chester Tester’s yearly data on their monitored sites is found on their website. There has also been success in health report and watershed report cards in the Chesapeake Bay and other watershed systems. The Chesapeake Bay Program website provides links to river health report cards for various rivers in the Chesapeake Bay watershed for people to track progress. A set of uniform report card criteria could be given to the other Bay jurisdictions to follow when reporting progress towards the 2025 nutrient pollution reduction goals so there is consistency and uniformity across all states. As monitoring programs continue to be improved, models can also be improved with the higher quality and consistent data. These models could then be used to form better predictions for adaptive management strategies. The models must be followed up with testing and monitoring to continue the improvement of the model predictions.

![Bay Barometer 2013-2014 [pdf]. Chesapeake Bay Program Bay Barometer 2013-2014. Chesapeake Bay Program](/site/assets/files/2438/figure3-500x649.png)

References:

- Chesapeake Bay Program. 2015. Bay Barometer 2013-2014: Health and restoration in the Chesapeake Bay Watershed. [pdf]

- Environmental Protection Agency (EPA). 2015. “How does it Work? Ensuring Results in the Bay.”

- Fincham, M.W., and D. Strain, 2012. "Is the bay recovery looking up?" Chesapeake Quarterly 11(4): 1-16.

- Gurbisz, C., and W. M. Kemp, W. M. 2014. Unexpected resurgence of a large submersed plant bed in Chesapeake Bay: Analysis of time series data. Limnology and Oceanography 59(2): 482-494.

- Kemp, W. M., W. R. Boynton, J. E. Adolf, D. F. Boesch, W. C. Boicourt, G. Brush, J. C. Cornwell et al. 2005. Eutrophication of Chesapeake Bay: historical trends and ecological interactions. Marine Ecology Progress Series 303(21): 1-29. [pdf]

- National Research Council (US). 2011. Committee on the Evaluation of Chesapeake Bay Program Implementation for Nutrient Reduction to Improve Water Quality. Achieving nutrient and sediment reduction goals in the Chesapeake Bay: An evaluation of program strategies and implementation. National Academies Press.

- University of Maryland Center for Environmental Science. 1997. The Cambridge Consensus: Forum on Land-Based Pollution and Toxic Dinoflagellates in Chesapeake Bay. Cambridge, Maryland.

Next Post > Mackay Report Card Workshop – Mackay, Queensland Australia 24 February 2015.

Comments

-

Adriane Michaelis 10 years ago

One of the things that stands out about Chesapeake Bay management is the number of missed goals. It’s important to recognize missed targets not as failures, but as points that highlight the need to adjust management strategies and the reality of goals. Aiming high (in terms of restoration targets) should not be discouraged, but effective communication of the reality of target goals is important to maintain public and political support of management aims.

-

Whitney Hoot 10 years ago

The Chester Tester program has been very successful in terms of citizen science. I think this connects back to our discussions of the challenges of managing and monitoring large-scale ecosystems. How can we do it? With citizen scientists! The benefits are two-fold: Not only are member of the public collecting data for free, but we're also engaging the community while generating interested in science and conservation. The world would certainly be a better place if citizen science was more widespread. That being said, there are challenges with citizen science too: What if the citizen scientists aren't reliable, or they don't collect good data? I previously worked at the Smithsonian Environmental Research Center and witnessed this issue firsthand. We planted more than 20,000 trees in the spring of 2013 - many of which were planted by volunteers and citizen scientists. I think it's key to distinguish between volunteers and citizen scientists; citizen scientists should have a long term commitment to the project. This makes a difference - the Boy Scouts who came out for an afternoon planted trees badly, but the long-term SERC volunteers who came out week after week planted trees well. This doesn't mean that volunteers working for a day can't do a good job, but they have a lower stake in the project than citizen scientists who are really invested in the work.

-

Wenfei Ni 10 years ago

This article focused on the development of Chesapeake Bay Program and analyzed its success and failure in a well-organized way. It is helpful for me to trace back and figure out the present situation of Bay management. And the author did catch the point between science and management, that the management should build on 'what we know' from science rather than be haunted by the uncertainties of 'what we do not know'.