Building Dinosaurs

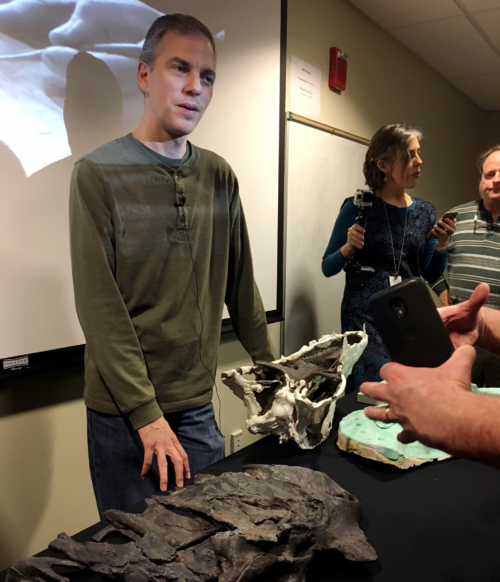

Emily Nastase ·Building Dinosaurs. With a name like that for a lecture how could I not be excited? So a few weeks ago I popped on over to D.C. for a seminar put on by the Guild of Natural Science Illustrators (GNSI). They had arranged for their colleague, Michael Holland, to explain the ins and outs of his career as a paleo-artist.

A little background on Michael: Growing up Michael had been torn between two worlds; the world of art and the world of science (something to which a few of us can empathize with, I’m sure). At Montana State University Michael was fortunate enough to be able to explore both avenues. He eventually graduated with his B.S. in Biology, but he was able to develop his talents as a sculptural artist as well. While at school, Michael was also fortunate enough to work in the paleontology department and marry his two skills together.

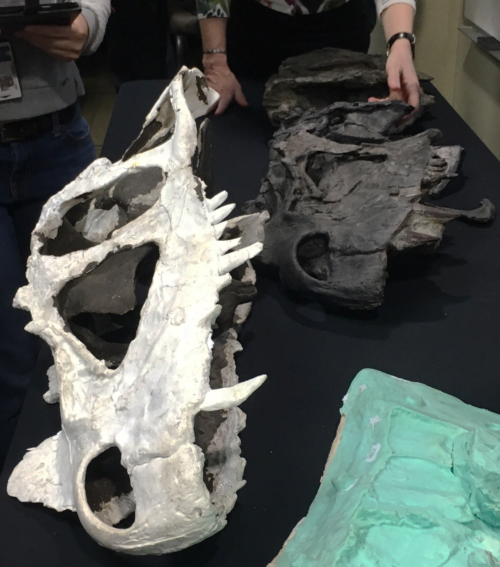

Now, Michael is the proprietor of Michael Holland Productions, a company that creates natural history exhibit “features”, AKA fossil reconstructions. Michael and his team are experts when it comes to molding and casting, sculptural reconstruction, and the mounting, installation, fabrication, and design of paleo-exhibits. He takes millions of years of data, a handful of bones and fragmented fossils, and some foil, clay, and paint and is able to piece together an amazing 3D scientific work of art. Michael’s favorite tagline explains what he does perfectly: "Building Dinosaurs, some assembly required."

After hearing him explain the process of building and reconstructing bones and fossils I was surprised by some of his techniques. When creating new bones for an exhibit, Michael begins with a crude wire-frame of the specimen. The wire-frame is created based on the individual size and shape of the specimen Michael is working with, as well as referencing other available bones of that species. He then overlays tinfoil on the wire-frame to create a planar surface. Tinfoil. I would never have guessed! Then Michael solidifies the structure with resin, adds details in clay (which includes beating his piece until it has an authentic fossil-like texture), and finishes the piece with a fresh coat of dirt-inspired brown paint.

The process Michael uses to create these features has changed very little over the decades, until recently. 3D printing brings a whole new tool to the table. When asked if he was concerned that 3D printers would “steal his job” Michael explained that he is not worried. This is simply a new technique that he will be able to utilize, and if anything, it makes his job easier! Now, instead of painstakingly making mirror-image bones for both sides of a specimen by hand, he can simply scan, digitally sculpt, and print a bone to his specifications. All that is left to do after the printing process is to assemble the pieces and paint on the finish.

One more point that Michael made sure to address was the controversy over whether or not museums should be displaying the original fossil or a manmade recreation. He stressed the issue as a point of contention between different parties involved with museum curation. Some people feel that seeing a manmade fossil construct is not as authentic as witnessing the original on display. They believe that showing a recreation or representation of an existing fossil is less honest and therefor has more room for errors in the guest's perception of that organism. Michael strongly supports the opposing argument. He believes that seeing a manmade fossil should not be viewed as a disappointment. This allows you to get a better understanding of the creature you are observing. Most fossils are difficult to discern details from, and oftentimes they are either flattened or crushed from spending so many years below ground. Recreating these fossils allows us to see the creature in the way it would have been viewed millions of years ago. Displaying recreations also allows museum curators and scientists to better preserve their original specimens. There is a lot of work involved in displaying the original fossils. And besides, it is much more interesting and exciting to see a full skeleton towering over you as opposed to a flattened hunk of rock!

As someone who also works at the intersection of the arts and sciences I found it absolutely fascinating to see Michael’s form of science communication. His way of creating and displaying entire skeletons of specimens is a beautiful and tangible way to view natural history.

Next Post > Evolving ecosystem health report cards to address issues of scale, acceptance, engagement, and behavior change

Comments

-

Dora Chen 6 years ago

Even though 3D dinosaur skeleton models are impressive, I like handmade skeletons more since the efforts we paid into that can not be replaced. And I hope that is a handicraft art which will not disappear.