"Whirling Disease" and Environmental Responsibility

Claire Sbardella ·As I learn more about science communication at IAN, I have begun to observe the plethora of methods available for science communication. "Whirling disease," written by professor R. T. Smith of Washington and Lee University, struck me as a particularly mesmerizing and pertinent example. R.T. Smith is the current producer of the Shenandoah Literary Magazine, and often contributes to other literary journals. He originally submitted this poem to Terrain.org, an online literary magazine with an environmental bent. If you enjoy reading poems and short stories with such a theme, then I highly recommend it. You can find Mr. Smith's original submission here. This poem stands out as an elegant lesson in how to creatively communicate environmental information to wider audiences.

Whirling Disease

By R. T. Smith

i.m. John Montague

Who are the men and women who deny

the damage, who say the earth, the sky,

the waters are beyond our powers?

I have seen brownies in the Rockies

swimming in circles like hounds by the fire

or a sycophant polishing a lie

for profit or the cold thrill of mischief.

The parasite behind the whirling disease

savages cartilage and skeletal

tissue in fish, dazes, bewilders

akin to senility, twisted circuits.

The victims can no longer feed

efficiently and make easy prey. Now

afflicted specimens have been witnessed

near Foscoe and on the old Watauga,

the rainbow trout likely to infect

brookies, and our own shameless species

spreads the damage, sportsmen dispersing

the lethal cells on their waders and flies,

for we are never so clean as we claim,

especially when we swear no harm

comes to the earth from our passage.

In a pool downstream of the Maury’s bend,

I once saw a young trout curling round,

spores on his scales, fins torn, the shimmer

of his glamor giving way to shadow,

and with all my stealth I edged closer,

parted weeds and reached into reflections,

fingers spread, easing till my hands were

beneath him, then crossed creel-wise

that I might lift him from confusion,

his worst dream, and leave him to swim

deftly downstream with the current

and his own kind. Now it’s clear he could not

be rescued, and I shiver at the thought

of those who claim nature immune

to our meddling. Glassy-eyed with greedy

smiles, they spin. May the waters close over

them, may they choke on their empty

victories, may the snelled hook still

glistening and with no mercy catch deadly

in their throats, ripping at every syllable,

delivering, justly, mischief’s cold thrill.

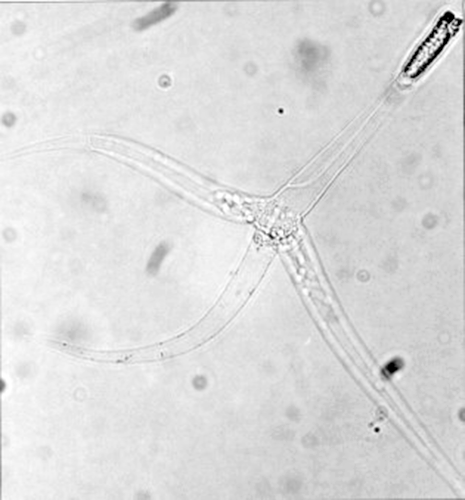

This poem uses a unique narrative structure to tell its story. It concentrates on a single moment: the instant the author tries to save a trout suffering from whirling disease, an illness caused by the parasite Myxobolus cerebralis. The poem uses and expands around this single moment, examining the philosophy and psychology of human impacts on the environment. After attempting to save the doomed fish, the author contemplates how humans contribute to climate change and the spread of disease, sometimes without even knowing. This poem discusses whirling disease as both a literal plague and also a metaphor for people who do not think that their actions affect the planet. It suggests that if we continue to refuse to care, then we, too, will be the ultimate victims of our planet’s destruction.

If we delve a little deeper into the techniques this poem uses to communicate the author's points, his unique use of poetic devices stands out. The author of this poem alters a variety of formal and well-known poetic devices to better convey the poem's message. The poem begins and ends with a variant of the heroic couplet, a structure commonly associated with Shakespeare’s plays. The couplets at the beginning and the end serve to give the poem a sense of introduction and of closure. However, the author subverts the form in two noticeable ways. First, traditional heroic couplets usually use full rhyme in which both the vowel and consonant sounds are alike, such as “bright/night” and “sighs/eyes”. In this poem, the author instead uses slant rhyme for both the beginning and closing couplets: “deny/sky” and “syllable/cold thrill.” Second, the poem subverts the traditional form by breaking the final couplet in two. The first line tags along with the couplet before it, while the last line, left alone, gives the poem a sense of imperfect closure, which makes the ending feel slightly less satisfying. The author has identified a problem, but he does not offer any solutions. Those are left for the reader to consider.

This poem uses another communication tool to encourage reflection in the audience after reading: empathy. In order to push the audience to consider on their own environmental impacts, the poem begins by encouraging them to empathize with the suffering animals. The image of the trout “curling round // spores on his scales, fins torn” from whirling disease is both visceral and disturbing. Even more disturbing are the diseases’ internal ravages, how it “savages cartilage and skeletal / tissue in fish, dazes, bewilders.” Spread by the influx of rainbow trout into non-native continents, whirling disease now affects several species of farmed and free fish. The parasitic spores spread so easily that they can be carried by fishermen who have not carefully washed their gear. “We are never so clean as we claim” the author laments, and this is true both literally and philosophically; not one of us is entirely guiltless of environmental impacts.

In order to better communicate the intended message, the central act of the poem – the author’s removal of the fish so that it might better swim downstream the Maury River – demonstrates both the author’s resolve and helplessness in the face of the trout’s suffering. The fact that the trout is a lost cause makes him “shiver at the thought / of those who claim nature immune // to our meddling.” The author's internal despair, and his futile attempt to save the fish, seamlessly transfers the audience's empathy to him. Suddenly the reader's focus has shifted to the author and his opinions, just in time to catch the poem's message: if individuals in power do not accept humanity’s role in environmental destruction, then there will be many more victims. “Glassy-eyed with greedy / smiles,” these people “spin” just like the infected trout, spreading the parasitical disease of inaction. And just like the poem’s structure itself, there is no real closure to this problem until people recognize their own culpability.

This poem is an extremely elegant example of how to apply poetic devices to harness an audience's attention, and by doing so, to impart information about an environmental problem. The poem also accentuates why I think that our work at IAN is so important: education cannot solve all environmental problems, but it can take great strides towards doing so. Creating report cards for businesses and governments that highlight strengths and problems and work towards solutions helps immensely. I am confident that as awareness grows, people will learn to empathize and looks for ways to mitigate their effects on the natural world, and learn to better manage our natural resources.