Sharing tools for stakeholder engagement and collaboration at the Chesapeake Watershed Forum

Suzanne Webster · | Environmental Literacy | Environmental Report Cards | Science Communication | Applying Science |Last month, several IAN staff members traveled to the National Conservation Training Center in Shepherdstown, West Virginia, to attend the Chesapeake Watershed Forum. The Forum is an annual regional conference hosted by the Alliance for the Chesapeake Bay. This year IAN was represented by Caroline, Emily, Dylan, Vanessa, and Suzi.

The 2017 conference theme was Healthy Lands, Healthy Waters, Healthy People. Presenters and attendees were encouraged to consider how the Chesapeake Bay and its health affect communities living within the watershed. With this theme in mind, IAN was excited to present two sessions this year, each focused on how different aspects of science communication can help individuals and communities explore their own connections with the natural world. Emily will discuss her session on art and science in a forthcoming blog post, and I will focus the current discussion around our team-led session on stakeholder engagement and collaboration.

During our 90-minute session, “Collaboration in practice: Tools for engagement,” we shared several strategies for bringing together diverse stakeholders and having robust conversations that translate into collective actions that protect environmental resources and improve the social, mental, and physical health of communities. In order to help the environment, scientists must accept that it is insufficient to simply study an ecosystem and make management recommendations based solely on observations of the natural world. Instead, protecting the environment necessitates both understanding how people value nature and managing human use of natural resources.

It is therefore important that we, as science communicators, move beyond one-way communication and dissemination of information, and instead encourage two-way dialogue, co-creation of knowledge, and collaborative problem solving between scientists and others. Inviting other stakeholders into the science and management discourse will lead to a more holistic understanding of the natural world and our relationship with it, and consequently, more effective management. Encouraging more representative participation in science could have the added benefits of increasing public environmental stewardship and support of science or management policies, as well as uniting and empowering communities.

In recent years, our work at IAN has increasingly involved communicating WITH others, rather than simply communicating TO them. During our interactive session at the Forum, we shared several tools for engaging groups in environmental science:

1. Role-playing exercises

Role playing requires participants to assume the roles of characters in a fictional setting. During a game, exercise, or skit, participants must consider situations and make decisions with the frame of mind of their fictional persona. An example of a role-playing exercise that we use at IAN is the "Get the Grade!" report card game. During this game, players are each assigned to play the part of a particular stakeholder who is involved in creating a report card for a fictional ecosystem. They must take turns voting on policy decisions, forming strategic partnerships, and making decisions that are in the best interest of their character, considering what their assigned stakeholder perceives to be the values and threats to the ecosystem.

We find that these types of activities are useful for engaging groups of people during workshops. Role-playing games are fun ice-breakers and provide participants with the opportunity to have a shared immersive learning experience that encourages everyone to not only participate and voice opinions in a safe, structured, judgement-free atmosphere, but also to be more open-minded and accommodating to other perspectives. Participants also enjoy many other benefits of role-playing—they can practice integrating new knowledge to solve complex problems, identifying shared goals, making decisions effectively as a group, empathizing with people with varying viewpoints, and other communication skills such as listening, and persuasive speaking.

2. Citizen science

Citizen science is a way to involve non-researchers in the scientific research process. Citizen science projects are extremely variable—for example, some projects, such as BioBlitzes, are one-time events that encourage volunteers in a small geographic area to participate in the data collection phase of biodiversity research, while other projects, such as water quality monitoring efforts with the Chesapeake Monitoring Cooperative, can be much more long-term and large-scale, and in some cases, can involve a far deeper degree of community engagement. Citizen science is a great tool to unite researchers with management practitioners, interested members of the public, and professionals from other fields. Citizen science also provides an active learning opportunity and promotes a deeper community stewardship ethic that can help diverse groups of people become more informed and empowered to improve their environment.

3. SNAP

We play SNAP with groups of stakeholders in order to articulate individual priorities and concerns, understand how individual opinions fit within the context of the group, and identify areas of agreement. At the Forum, we asked participants “What do people in your communities value about the Chesapeake Bay?” and instructed each person to provide a few one- or two-word answers written on separate Post-it notes.

We shared answers as a large group and when anyone heard another answer that matched their own, they yelled "Snap!" and joined the matching Post-its to form a chain. Individual Post-its and chains were organized into diverse, emergent categories, such as "Human Health," "Biodiversity," and "Economy". Finally, participants were asked to place two stickers on the categories that they felt deserved to be highest priority, considering their own values, as well as what they learned from the other responses and discussions during the group activity.

SNAP helped our group identify major themes and visualize consensus. For example, during our session, the categories of "Recreation" and "Food" proved to be the most populated by Post-it notes; however, the "Water Quality" category was eventually voted as the group's highest priority in the end, despite originally receiving less than a quarter of the Post-it notes as the most-populated categories. Another similar technique that we use to visualize consensus hidden within a group of one-word answers is to create a word cloud, which clusters all of the words and adjusts the font size according to how often they are repeated.

4. Conceptual diagramming

Collaboratively creating conceptual diagrams is a way creatively integrate multiple stakeholders' ideas and combine diverse perspectives into a cohesive image that represents a shared vision of an ecosystem, or a "coupled" system. During this process, a group of stakeholders receives a base map of an ecosystem and they work together to "fill in" the values and threats of the place of interest, using symbols or other artistic representations. This process necessitates planning, discussion, flexibility, and strategy in order to incorporate everyone's priorities, and also requires that stakeholders communicate (and listen!) effectively so the final version of the diagram is representative of the entire group.

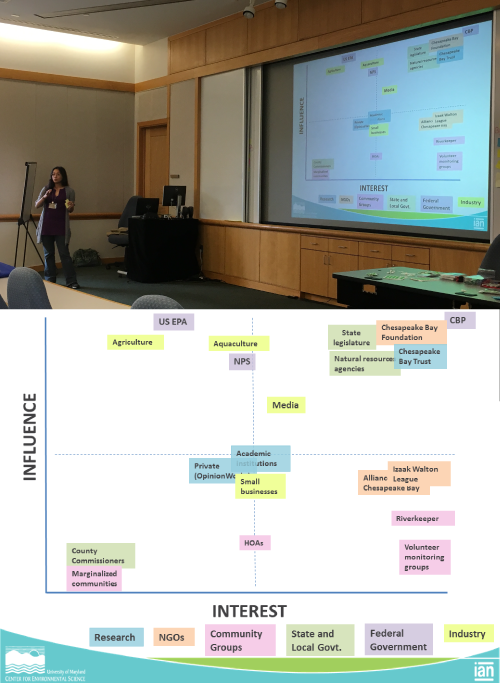

5. Stakeholder mapping

Finally, stakeholder mapping is a useful activity that encourages groups to take a step back from thinking about the specifics of an ecosystem, and instead focus on the many people who hold a stake in the ecosystem. During this activity, participants identify all stakeholders relevant to a particular situation and then "map" them according to their degree of influence and interest in the situation. The process of stakeholder mapping is useful for identifying who should be involved in environmental management or reporting efforts and how stakeholders should prioritize either engaging or empowering one another, depending on current positions on the map.

This activity is particularly useful after completing one of the other activities described, such as SNAP or conceptual diagramming, which identify values and threats to an ecosystem. Once values are collaboratively identified, for example, a stakeholder mapping exercise can prompt people to consider such questions as, “Who should be included in a discussion to preserve these values?” or "What communication strategies could help our stakeholder network accomplish our collective goal?" Stakeholder mapping can also be extended to include a basic social network analysis activity, during which groups can use the map to identify any interest groups by noticing clusters of similarly-positioned stakeholders, and also to visualize network connectivity by drawing lines between stakeholders and noticing who is more centrally vs. peripherally connected and who has the strongest relationships with other stakeholders.

Overall, we believe our conference session was a success. We had fun teaching participants about several tools that they can use to engage groups of people in their own places of work, and we especially enjoyed the opportunity to give attendees a taste of three games we use often in our own workshops. We are already looking forward to next year's Forum!

About the author

Suzanne Webster

Suzi Webster is a PhD Candidate at UMCES. Suzi's dissertation research investigates stakeholder perspectives on how citizen science can contribute to scientific research that informs collaborative and innovative environmental management decisions. Her work provides evidence-based recommendations for expanded public engagement in environmental science and management in the Chesapeake Bay and beyond. Suzi is currently a Knauss Marine Policy Fellow, and she works in NOAA’s Technology Partnerships Office as their first Stakeholder Engagement and Communications Specialist.

Previously, Suzi worked as a Graduate Assistant at IAN for six years. During her time at IAN, she contributed to various communications products, led an effort to create a citizen science monitoring program, and assisted in developing and teaching a variety of graduate- and professional-level courses relating to environmental management, science communication, and interdisciplinary environmental research. Before joining IAN, Suzi worked as a research assistant at the Marine Biological Laboratory in Woods Hole, MA and received a B.S. in Biology and Anthropology from the University of Notre Dame.