An Array and a Ray

Kate Petersen · | Learning Science |

This blog post is the second of a two-post series examining cownose ray (Rhinoptera bonasus) history and ecology in the Chesapeake Bay.

Hauled aboard a fishing vessel on the Chesapeake Bay, most of the creatures caught in the net would never return to the sea. But one supple parallelogram with a kind smile was afforded a less adverse fate. After enduring a quick surgery to implant a small transmission device, this cownose ray (Rhinoptera bonasus) was returned to the water where she continued on her mysterious fall migration. Dr. Matthew Ogburn, a marine biologist at the Smithsonian Environmental Research Center (SERC), watched the ray descend, an increasingly vague shape finally replaced by lonely green water.

It was the summer of 2014 and Dr. Ogburn was collaborating with a team of scientists to map the rays’ clandestine migration pattern as part of the Smithsonian’s Movement of Life Initiative. The scientists involved in this international effort have identified migration patterns as being a crucially understudied facet of the ecological sciences and work together to elucidate migration pathways over broad swaths of the earth. Dr. Ogburn knew that cownose rays were a particularly apt subject for this research endeavor as, in addition to being a migrating species, they were blamed for the collapse of bivalve fisheries and were subject to wanton and unregulated slaughter in Chesapeake Bay bow fishing tournaments. The lack of coherent information about cownose ray migration behavior would make it difficult to develop appropriate conservation strategies should they become necessary.

Through the crests and troughs of cownose ray popularity,

Dr. Ogburn had continued to outfit rays with transmission devices. His team spent three seasons tagging rays

caught as bycatch by fishing

industry collaborators. They tagged 42 rays in Maryland, Virginia, and Georgia.

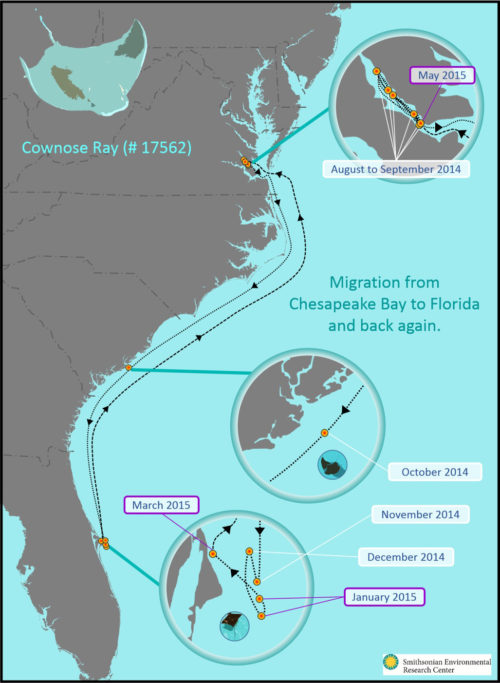

These rays would ultimately lead Dr. Ogburn’s team to their wintering grounds,

revealing a migration pathway along the Eastern Seaboard. But how did a team of

scientists follow 42 individual rays on such an Odyssean trek? They used an

array, or, more precisely, an array of arrays, to track the rays.

For years,

marine scientists have been deploying arrays of passive receivers to track

species of interest along the east coast of the United States. Scientists like

Dr. Ogburn implant transmission

devices into the animals they’re studying. Each device transmits a unique signal,

allowing individual animals to be identified by their “ping.” When the animal

swims near a receiver in an array, its “ping” is detected and recorded. These receivers are periodically

retrieved, their data is downloaded, and then they are redeployed.

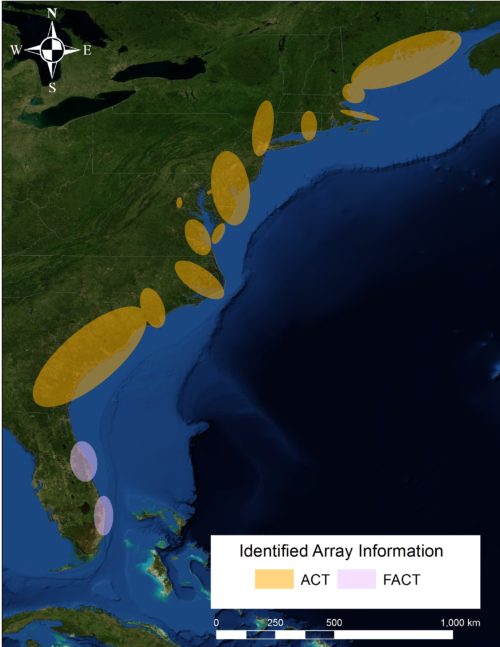

Originally, each scientist’s study area was limited by individual funding and infrastructure parameters, basically, the number of receivers they could afford to buy and maintain. This significantly limited their ability to track far ranging species. In 2006, these scientists began to develop a coordinated array sharing effort, eventually forming the Atlantic Cooperative Telemetry Network (ACT Network). Between the ACT Network arrays and the similarly organized Florida Atlantic Coast Telemetry Network (FACT Network) arrays, marine scientists now have access to data from arrays stretching from Maine to the Caribbean.

Regardless of where they were originally tagged, Dr. Ogburn’s rays “pinged” all the way down to Cape Canaveral, Florida, which, for Chesapeake Bay rays, represents a roughly 900-mile (one way) migration. This finding has important conservation implications, because it suggests that the appropriate management scale for cownose rays involves the entire east coast and that Chesapeake Bay ray populations could be impacted by human activity, not only in the Bay, but also in Florida, or anywhere in between.

Dr. Ogburn’s team also found that most rays returned to the same region where they were originally tagged. Currently, there is not enough data to determine whether this homing behavior is ubiquitous in the species. If cownose rays return each year to the same region to breed and give birth, unique pockets of genetic diversity could be wiped out by poor management in localized areas. Dr. Ogburn explains, “If they’re really tied to one specific place, then you’ll be removing a whole piece, a whole unique segment, from the population.”

In March 2017, Maryland became the first state to enact preliminary protections for cownose rays. Bow fishing tournaments were temporarily prohibited and the Maryland Department of Natural Resources (DNR) was tasked with developing a fisheries management plan. This is good news for Chesapeake Bay cownose rays, but Dr. Ogburn’s work suggests that a meaningful management plan may ultimately require attention from natural resource agencies across the Eastern Seaboard—a valuable insight gleaned from an array and a ray.