Building Trust in Science

Annie Carew ·Marylanders feel a deep pride and connection to our environment. Our lives and livelihoods center on nature: sailing, hiking, fishing. It permeates our culture—just ask any Marylander about blue crabs or oysters. Baltimore has two professional sports teams named after birds. The Chesapeake Bay sits at the heart of this pride, the crown jewel of Maryland ecology and culture. We love our Bay.

It’s only fitting that Maryland is at the forefront of climate resilience. The upward creep of the sea on the Eastern Shore affects our farmers and communities that have lived on the Shore for hundreds of years. Roads on both sides of the Bay flood on a regular basis, either from unusually high tides or large amounts of rain. Downtown Annapolis is becoming notorious for this; the City routinely provides sandbags to businesses on Dock Street. These changes threaten our health and safety.

The University of Maryland’s Climate Resilience Network strives to face these challenges. The Network brings together top researchers, decision-makers, and community leaders from across the state. Network partners include our collaborators at the Charles County Resilience Authority, Maryland’s Department of Natural Resources—and us. IAN is a member of the Climate Resilience Network, and we have been working on climate resilience since the statewide Coastal Adaptation Report Card. Our climate resilience work, and the existence of this network, reflects that quintessential Maryland love for the environment.

I attended the annual “Scientists Serving Communities” workshop in January. I thought it was very cold that day (it was, but I didn’t know how much colder it would get). Last year’s workshop was thought-provoking and interesting, and I expected this year to be the same.

I was more than interested; I was inspired. Now more than ever, the community-driven approach to science is necessary to improve people’s lives. This approach—which centers people’s needs—is and must be the future of science. Sitting in a room surrounded by people with similar ideas and priorities, I felt energized.

As at last year’s workshop, there were panel discussions of climate-related challenges. I attended sessions on flooding, infrastructure, and agriculture. Notice that these topics focus on the human impacts of a changing climate. Human communities are threatened by flooding and heat; human communities require infrastructure; human communities grow their food. At every session, the scientists asked a question of the audience: “What do you need from us?” They want to know what community members want and need from science. The answers to this question will drive decision-making and improve people’s lives.

I was particularly struck by the opening plenary session. Dr. Lars Peter Riishojgaard, who directs UMD’s Earth Science System Interdisciplinary Center, spoke of a “valley of death” between science and stakeholders. There’s a gap between science and action. Many academics do their research in isolation, with limited understanding of stakeholder needs. Crossing the valley of death is critical to applying science to real-world issues, and that’s where IAN works. We guide scientists and stakeholders across the proverbial valley.

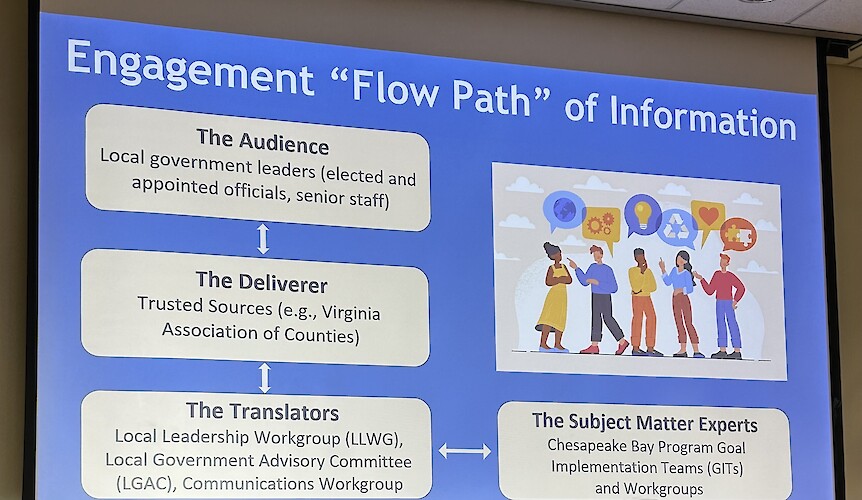

Kristin Saunders, Director of the Center for Watershed and Bay Resilience (and former IAN colleague at the Chesapeake Bay Program!), talked about trust in science. Kristin emphasized that information from a trusted source is more likely to be accepted and implemented—and trust requires relationships. Healthy relationships are not one-sided; information flows both ways. This is the true meaning of engagement, and it is a principle that we keep in mind as we practice our stakeholder engagement. As scientists and academics, we can become entrenched in our focus on complex, technical science. The perspective of community members—the people who are actually living with environmental changes—is critical to direct our research.

The first speaker at the plenary was Dr. Patrick O’Shea, the chief research officer at UMD College Park. He summarized the theme of the workshop with one simple phrase, which I wrote down verbatim: “In order to be trusted, we have to be seen to be serving.” Science can and will provide the solutions we need to face large-scale challenges. The climate is changing, and will continue to change; we as scientists can help adapt to and prepare for that change. Our work—our science—serves communities. It’s all in the name.

About the author

Annie Carew

Annie Carew graduated from UMCES with a Master's degree in 2019. Her thesis research examined the effects of genetic identity on aquatic plant restoration success. Annie's research interests include coastal management and climate adaptation. At IAN she works on workshop facilitation, data visualization, document design, data analysis, and social media management. She is an enthuiastic birder and botanist, and can often be found wandering in the woods on the weekends.