Changing Perceptions of the Chesapeake Bay and Its Watershed

Bill Nuttle · | Environmental Literacy |

One of the landmarks that I look for is the bridge where I-81 crosses the Susquehanna River at Great Bend, Pennsylvania. Crossing the Susquehanna at Great Bend, near the border between New York and Pennsylvania, has always felt like the point at which I arrive at the watershed. That changed on my last trip.

The fact that I think about the Chesapeake Bay’s watershed at all is a direct result of a campaign by the Chesapeake Bay Commission, an advisory panel with representation from Virginia, Maryland, and Pennsylvania. To increase public awareness of the scale at which human activities impact the Chesapeake Bay, the Commission installed signs marking the boundary of its watershed along major highways in the 1990s.

Because New York is not part of the tri-state Chesapeake Bay Commission, the northern boundary of the Chesapeake’s watershed was not marked. Recently, the Upper Susquehanna Coalition has stepped up to fill this gap. The Upper Susquehanna Coalition is comprised of a number of local conservation agencies that have come together to work to improve water quality in the river and natural resources in its watershed. This region encompasses the watershed that feeds the Susquehanna between its headwaters and a point near where the river crosses into Pennsylvania for the third time.

Through the initiative of the Coalition, visitors to the Whitney Point rest stop, located 36 miles north of Great Bend on I-81 south, are greeted by a poster informing them that they are in the watershed of the Chesapeake Bay. The poster also provides information on conservation issues in the region and the work of the Upper Susquehanna Coalition. After stopping there during a trip in October I now know that I-81 enters the Chesapeake Bay watershed at Tully, New York, 70 miles north of Great Bend.

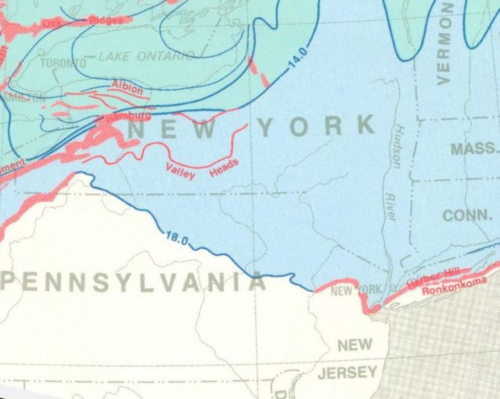

The flat, featureless landscape around Tully provides the traveler with no hint of its connection to the great estuary 225 miles to the south. However, the significance of this connection extends beyond just crossing a hydrologic threshold. The landscape between Tully and Great Bend is the newest portion of the Chesapeake Bay’s watershed. Indeed, this can be considered to be the birthplace of the Chesapeake Bay.

The Upper Susquehanna did not exist 18,000 years ago. The Laurentide ice sheet covered half of North America, extending from the Arctic to a point 20 or 30 miles south of Great Bend. Over the next 4,000 years a gradually warming climate melted the ice sheet, and the ice front retreated north of Tully. This uncovered the Upper Susquehanna basin and gave the Susquehanna watershed its current form. The melting ice sheet also sent torrents of freshwater into the ocean, swelling its volume. Rising sea level flooded the lower reaches of the Susquehanna River, creating the Chesapeake Bay.

Encountering the Susquehanna River in its moment of muddy repose at Great Bend will always bring to my mind the tidelands of the Chesapeake Bay, our shared destination. However, the next time I drive past Tully, New York, I will be reminded of the cataclysmic events that happened there thousands of years ago. The ice sheets of Greenland and Antarctica are now melting because of our warming climate, and the birth of the Chesapeake Bay foreshadows a not too distant future of pervasive coastal change.