Consumer behavior and climate change: when is enough, enough?

Meghna Mathews · 2 commentsFor hundreds of years, society has been greedy. So much so that we are living in a world of scarce resources. The readings this week led me to think that no matter how much we have, we are never truly satisfied. This topic resonated with me because my undergraduate career focused on environmental economics and its implications for climate policy. I received my B.S. from the University of Maryland College Park in environmental science and policy, with a concentration in environmental economics.

Many of us are fortunate enough to live very comfortably, yet we still desire the most materialistic things. You may be wondering, what does society have to do with economics? Society and the economy are interdependent. As the economy grows, it is reflected in societal growth as well. Individual behavior is a key factor in the drive of economic growth.

Last week, our class was joined by economist Lisa Wainger, and she discussed the importance of economic value and efficiency, especially in the context of the environment. Efficiency involves maximizing benefits per level of inputs and how efficiency is a guiding principle for deciding who gets which resources. Our discussion about resource allocation prompted me to think about environmental justice, as many environmental injustices are a result of inefficient resource allocation.

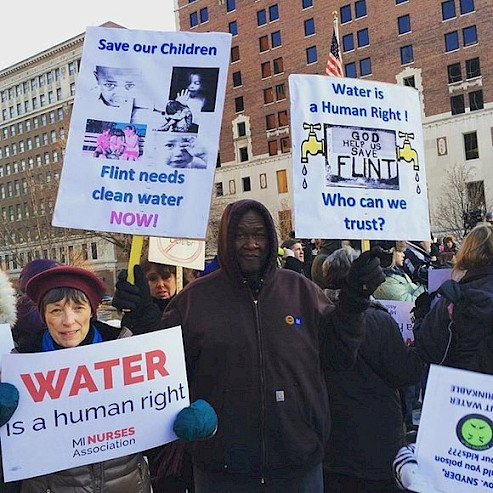

This can be exemplified through the water crisis in Flint, Michigan, which began on April 25, 20141. This crisis is an environmental injustice that was ultimately induced by the effects of climate change, as the switch was promoted by state-appointed managers as a cost-saving measure of climate change. The city failed to provide clean water to the citizens of Flint, Michigan, which led to an increase in the water’s lead levels as well as an increase in humans’ blood lead levels. The city of Flint, Michigan is primarily of low-income and minority populations2 who are already at a higher risk of lead exposure. The water supply was switched from Lake Huron to the Flint River, which had not been treated with an anti-chemical that would prevent lead particles from being released into the pipelines. This contaminated water was corrosive, which General Motors realized immediately since it was ruining their pipes. While the corporation took measures to switch the water supply once again, the people of Flint, Michigan suffered for years from the contaminated water through physical symptoms and mental health effects. This example shows how corporate greed took over. Selfishly enough, money was considered at the expense of human health. This is a common tradeoff that occurs when it comes to environmental damages.

As we can see, the Flint Michigan water crisis is a resource allocation issue as well because many communities are not able to find qualified operators to regulate, monitor, and test the water quality. In addition to this resource, or lack thereof, many families residing in Flint, Michigan are unable to afford maintenance costs and water quality enhancements3.

When environmental economics is in question, we must think about consumer behavior, as behavioral economics can inform environmental and public policy, which can be done in two ways4:

- Improving cost-benefit analyses through strategic adjustments to nonmarket valuation techniques, and

- Informing policy mechanism development to influence environmental behavior.

Our individual wants and desires are often influenced by others. Our own preferences sometimes take over and we do not realize how much risk we are posing on others. This is known as socially-directed preferences5, where people acknowledge that their own consumption habits can have negative effects and consequences on others through the imposed environmental damage. In this case, if we acknowledge it to a certain extent, we may be willing to reduce our consumption of environmentally harmful goods. This would mean people would act altruistically. Are we as a society altruistic, though?

By nature, humans tend to be selfish people. We can clearly see it through the effects of climate change. Sea levels are rising, air and water quality are reducing, soils are depleting, and storm events are occurring more frequently. According to the Intergovernmental Science-Policy Platform on Biodiversity and Ecosystem Services (IPBES), humans are changing nature on a global scale and the consequences are unequally distributed6. The effects of our consumption habits are becoming worse due to population growth. Since the 1970s, the global population has doubled. To accommodate this growth, consumption has increased by 45% per capita, which has led to devastating declines in ecosystem health.

One of Wainger’s conclusions was that the most efficient policy, as defined by economic philosophers, allocates scarce resources by finding options where aggregate benefits exceed harms. However, we are constantly looking for benefits and we often disregard the harms. In a perfect society, this would be ideal. However, tradeoffs are necessary in resource allocation, which our class read about in Holland’s case study of the distributional effects of air pollution from electric vehicle adoption. Many of the environmental benefits that were associated with electric vehicle adoption were distributed by income, race, and other urban measures.

Although it is complex, understanding the relationship between consumer behavior and climate change is critical in terms of economic decision-making and public policy. Many consumers, which are regular individuals, are not capable of determining which behavioral changes are worth doing. Studies have shown that there should be more focus on individuals making climate friendly behavior the “easy behavior” with regard to a correct reflection of carbon footprint reductions. When we make economic decisions, we must ask ourselves, why do we want the things we do? How is it going to benefit us in the long run? When is enough truly enough? These are questions we must consider for the health of our planet, especially when it comes to the use and misuse of natural resources.

References:

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). (2020, May 28) Community Assessment for Public Health Emergency Response (CASPER): Flint Water Crisis, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Retrieved from https://www.cdc.gov/nceh/casper/pdf-html/flint_water_crisis_pdf.html

- Campbell, C., Greenberg, R., Mankikar, D., Ross, R. D. (2016, October) A case study of environmental injustice: the failure in Flint, National Library of Medicine. 13(10): 951. Retrieved from https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC5086690/

- Water Resources Alliance (2022) How to prevent another Flint, Michigan water management crisis, Water Resources Alliance. Retrieved from https://alliancewater.com/how-to-avoid-being-flint/

- Haščič, I., Johnstone, N. (2012, July) Behavioral economics and environmental policy design, OECD. Retrieved from https://www.oecd.org/env/consumption-innovation/Behavioural%20Economics%20and%20Environmental%20Policy%20Design.pdf

- Dasgupta, P. (2015) Consumer behavior with environmental and social externalities: Implication for analysis and policy, St. Andrews. Retrieved from https://research-repository.st-andrews.ac.uk/bitstream/handle/10023/8687/DSUU_second_revision_100115.pdf;sequence=1

- Begum, T. (2019, December 12) Humans are causing life on Earth to vanish, Natural History Museum. Retrieved from https://www.nhm.ac.uk/discover/news/2019/december/humans-are-causing-life-on-earth-to-vanish.html

About the author

Meghna Mathews

Meghna Mathews is a graduate research assistant and a second year master’s student at the UMCES Appalachian Laboratory, working under Dr. Xin Zhang. Mathews is working on stakeholder engagement through a project aiming to understand stakeholder perspectives of nitrogen pollution and management strategies in the Chesapeake Bay. Additionally, she is researching food insecurity in Baltimore, Maryland and how urban agriculture can be used as a method to reduce the issue.

Next Post > Generating Collective Knowledge at the Potomac Open House

Comments

-

Colin Vissering 3 years ago

Meghna - interesting post that combines a discussion on the nature of human behavior and decision-making along with how economic analysis can illustrate how this behavior influences resource imbalance and can also help develop options for policy makers. Much like the study of electric vehicles we covered and the somewhat surprising variations in the distribution of benefits, many of our activities are difficult to accurately assess without these economic tools that provide an unbiased analysis of the data. I think we need to more deeply embrace economic tools as we develop ecological solutions to climate change and related environmental challenges, since this is key to providing objective evaluation of options. There are times when a "green" solution seems to be the best idea, but upon further evaluation it may create inequity in property values, impact low-income communities disproportionately, and not be the most cost-effective of a range of solutions.

-

Mary Efird 3 years ago

Meghna, this is such a powerful post. I agree that the greed we see every day in our society can be really frustrating, and I really believe that greed is a huge reason that our environmental crisis is as bad as it is. I remember discussing ecosystem services in another class I took last spring and thinking that I don't think that requiring corporations to pay for damages to ecosystem services would do any good because as long as they can still make more money damaging the ecosystem, they won't care about fees to be paid. I don't say this to be pessimistic, I just think that addressing the issue of greed is a huge hurdle in the fight to mitigate climate change and finally update environmental policies. Great post!