Engage inside, stay outside: look from politics, practice from ecology

Haoyu (Peter) Chen ·2020 is a year full of events. For me, this year I was trapped at home and it was very boring. For the country, COVID-19 occurrences in various places have caused the government's workload to soar. For the world, this headache is still the slowdown of global economic growth with a deterioration in the natural environment. At different levels, this affects what groups worry about and what they see will be different. You may not participate in politics, but you may realize that you are affected by politics, especially when you start to think about how it alters the use of natural resources. Just like Frank Thone, 80 years ago, you may be suitable to learn a subject called political ecology.

What is political ecology? How do we learn this subject? And what does it teach us? You may be wondering why you should learn it; it has powerful functionality, and I believe it is important to understand its core points. Last week, Daniel J. Read, a political ecology scholar whose interest in studying Indian tigers, brought us its information in the MEES620 class.

'I originally think it is a traditional study that has existed for a long time.' 'Yeah, surprisingly, Political ecology is a new major developed recently.'

An exchange between our course professor and guest lecturer, Dr. Read

Political ecology is actually a novel subject. Its etymology comes from Frank Thone's 1935 article "Nature Rambling: We Fight for Grass"1 which was only revived in 19752 (Eric R. Wolf 19722). Although half a century has passed, the subject still has no fixed definition3, but it can be used to study the influence of the political process on local resource rights. Feminist ecology, decolonizing political ecology, etc. are its recent hot directions, but Dr. Read also pointed out that these topics are not unique to political ecology. Political ecology should be very interdisciplinary4, you can find its shadow in any issue about ecology or politics, because politics is often an important guarantee factor for environmental protection, especially in international cooperation, the allocation of resources is inseparable from the government's planning and implementation.

Every anthropology studies society and the environment from one aspect and political ecology is no exception. Political ecology, like most anthropological research, can be studied through traditional methods such as field trips. Dr. Daniel proposed that this method can be called "deep hanging out". But they are more focused on studying the consequences of multi-scale politics on resource users. Such consequences can be presented through economic data (such as GDP) or environmental data (such as tree biodiversity) both.

A TYPICAL EXAMPLE OF A CASE STUDY IS SHOWN ON A HUNDRED YEARS DEBATING PROBLEM IN KISSIDOUGOU, GUINEA: WHETHER KISSIDOUGOU SUFFER DEFORESTATION OR NOT?

In Kissidougou, dozens of policies defending deforestation had been established for hundreds of years but proved to be a trick by the governor. Several policies were implemented by the local village governor of Kissidougou, Guinea. But remote sensing data, archives, and oral evidence all showed no deforestation during the past hundred years. The ultimate cause of this farce is believed to lie in the discourse of the governor. The power of the governor's slogan is so powerful that it changed the behavior of locals and reduced their control of forest resources. The forest now becomes more vigorous, but it may also get worse under the operation of assigned watchers who are not familiar with the forest as local.

Mountain lot for sale in Panama. Licensed under CC. (URL:https://www.coastalpanamaproperties.com/search/pa-8/mountain-lot-for-sale-in-altos-del-maria-panama/970748/)

SCALE CONSIDERATION IS THE MAIN THEME OF POLITICAL ECOLOGY.

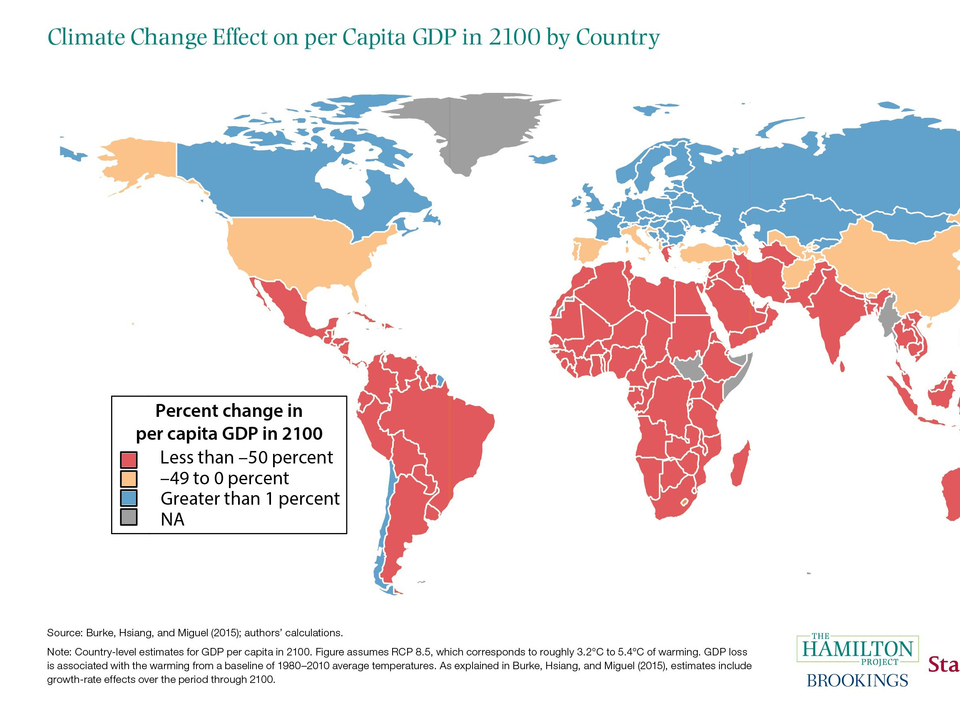

Observing events from different scales is an important feature of political ecology. However, the scale is divided differently into different issues. In Kissidougou's research, it is divided into the manager, the relationship of manager, and state and world economy. Campbell6 divided it into local, national, and global issues of global sea turtle conservation. Campbell believes that the high population of sea turtles in a particular region does not mean sea turtle conservation project is unnecessary. On the contrary, the idea of 'conservation for more profit' should be restrained. The development of ecotourism7 is regarded as an important means of environmental protection. Another example is that northern countries have not been affected by climate change too much (such as temperate Goldilocks zone8), so it is wrong not to establish a climate-change corresponding mechanism. From a global perspective, temperature and sea-level rise are more common phenomena. As Bennett9 suggests, the scale is only correct when it is where it should be. Considering the transcending of scale is very effective in developing solutions. This kind of transcending requires us not to be confined to current interests but to focus on higher and even global interests. At this time, things that are difficult to make decisions will become simple. Our lecturer proposed, NGOs and some associations could be the boundary breaker for scale transcending.

INDIGENOUS PEOPLE ALWAYS KNOW HOW TO PROTECT THE ENVIRONMENT THAN OTHER PEOPLE DO.

The role of discourse is strong, but the role of the representative is not necessarily positive. Narrative or the application of knowledge, from complex descriptions to simple metaphors, is a powerful tool to represent a version of reality and can play an active role in shaping reality9. The topic of indigenous people is a classic topic of political ecology. Wounaans10 fought fiercely with the local government on the land in Colombia because of the issue of land ownership, and the government did not want the indigenous people to reduce their control over the land. They used discourse and regarded Wounaans as illegal. A similar example to poaching was suggested by a classmate. Traditional hunting activities and cultural backgrounds were demonized by the governor. The energies of the indigenous people have shifted from supporting land ownership movements to justifying their innocence (Such as the Chile indigenous movement11). Runk, J. V.12 suggested that Wounaans' linkage with forest makes them more powerful in forest conservation. The mainstream culture that regards currency as its real benefit is impacting the secondary culture that considers the environment as its benefit, especially in the Third World. Third world war happens every day in the corner of the world. In today's world, this kind of conflict between development and conservative is intensifying. The problem of Wounaans is not an exception. If the environment is really a concern, the government should consider giving up part of the right for speaking in environmental protection but not treating them as enemies.

After class, we are still facing many challenges. You may think that there are difficulties ahead that you can never overcome. Just like when I wrote a blog at the beginning, it feels impossible to start. But in fact, when you jump out of the original scale and look at it from the perspective of an outsider, the stone of difficulties may also be a milestone. You think you will die, but you keep living, day after day after a terrible day.

LITERATURE CITED

1. Thone F. (1935). Nature Ramblings: We Fight for Grass. Retrieved October 19, 2020, from https://www.sciencenews.org/archive/nature-ramblings-we-fight-grass

2. Wolf, E. R., & Hansen, E. C. (1972). The human condition in Latin America (No. 001.3 W8311h Ej. 1 002717). Oxford University Press,.

3. Chatterjee, D. K. (Ed.). (2011). Encyclopedia of Global Justice: A-I. Springer Science & Business Media.

4. Biersack, A., & Greenberg, J. B. (Eds.). (2006). Reimagining political ecology. Duke University Press.

5. Fairhead, J., & Leach, M. (1996). Misreading the African landscape: society and ecology in a forest-savanna mosaic(Vol. 90). Cambridge University Press.

6. Campbell, L. M. (2007). Local conservation practice and global discourse: a political ecology of sea turtle conservation. Annals of the Association of American Geographers, 97(2), 313-334.

7. Zeppel, H. (2007). Indigenous ecotourism: conservation and resource rights. Critical issues in ecotourism: Understanding a complex tourism phenomenon, 308-347.

8. Borunda, A. (2019, April 22). Inequality is decreasing between countries-but climate change is slowing progress. Retrieved October 19, 2020, from https://www.nationalgeographic.com/environment/2019/04/climate-change-economic-inequality-growing/

9. Bennett, N. J. (2019). In political seas: engaging with political ecology in the ocean and coastal environment. Coastal Management, 47(1), 67-87.

10. Giraldo, C. M. (2019, February 28). Panama's indigenous groups take land fight to the international stage. Retrieved October 19, 2020, from https://news.mongabay.com/2018/08/panamas-indigenous-groups-take-land-fight-to-the-international-stage/

11. Carruthers, D., & Rodriguez, P. (2009). Mapuche protest, environmental conflict and social movement linkage in Chile. Third World Quarterly, 30(4), 743-760.

12. Runk, J. V. (2009). Social and river networks for the trees: Wounaan's riverine rhizomic cosmos and arboreal conservation. American Anthropologist, 456-467.

About the author

Haoyu (Peter) Chen

Haoyu (Peter) Chen is a first year master’s student in the University of Maryland’s Marine Estuarine Environmental Sciences program, with a concentration in cell & molecular biology. He is advised by Dr. Chen Feng studying the mechanism of cold adaptability of Synechococcus, a widespread phytoplankton in marine, during winter. In addition, Haoyu is also interested in biodiversity using molecular methods. Recently, he is working to understand the systematics of hydrozoa, a benthic stage of jellyfish, near the coast of China.