Fresh fruit, virtual land, and conference ribbons: what can we learn from a network perspective?

Kelly Hondula, Natalie Yee · | Applying Science | Learning Science | 9 commentsKelly Hondula, Natalie Yee

After learning about how to construct and interpret social network data sets the previous week, the MEES Coupled Human and Natural Systems class spent a week delving into understanding the types of questions that social and natural scientists investigate using network analysis. We explored social networks of communication, global trade networks, and multi-level networks through discussion of three recent publications about the theory and application of social network analysis (Bodin et al 2016, Prell and Lo 2016, Prell et al. 2017). Each of these three frameworks tackled very different types of networks, but each presented opportunities for the class to reflect on how the structure and behavior of networks both influences, and are influenced by, our everyday activities.

1. Social networks of individuals

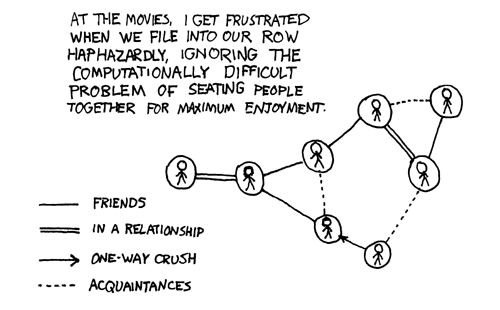

Perhaps the most ubiquitous conceptualization of networks is of individual people, joined by their communication ties or personal relationships. In this framework, people are the nodes in a network and the links are their relationships, for example how frequently any two individuals contact each other. This is the basis of the approach taken by Jasny et al (2015) to evaluate key actors in the US climate policy network, where they found that high levels of transitivity amplify partisanship when it comes to communicating information about climate change science.

The implications about transitivity in the work by Drs. Prell and Lo (2016) became immediately apparent to our lives as graduate students, as the class wondered whether and how to put into practice the results of this modeling study. One of the surprising findings was that in order to maximize the amount of knowledge gained in forming new ties in a network, pursuing experts was not as successful of a strategy as pursuing a transitive strategy, or seeking out ties with friends of friends.

We imagined how this strategy could play out in the context of a young graduate student navigating a scientific conference: how much time and energy should he or she spend trying to meet luminaries in their field? Should they seek out meetings only with award winners and ribbon-bearers? Is it best to try to get a mutual friend to offer an introduction?

2. Global trade networks

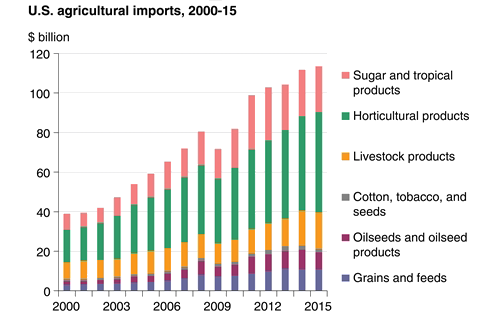

Another framework for network analysis is to investigate connections between geopolitical units like countries through their trade flows. In this type of analysis, countries (or cities, states, or regions) are the nodes in the network, and links represent the existence or magnitude of exports and imports between countries. Even though this network is global in scale, its implications are apparent to consumers based on the selection of produce available in grocery stores. Trends in trade data from the USDA show how increased globalization over recent decades has expanded options for US consumers—our diets are no longer restricted by which foods are in season locally!

Dr. Prell and colleagues used this type of trade network data to identify a positive feedback between a country’s land use patterns and its position in global network hierarchies, where “land exporters” form ties with wealthier countries, and those ties are then reinforced over time to maintain land-intensive export trade flows to wealthy countries. This type of research is emblematic of a field of study that investigates globalization through the flows of “virtual” goods that are embodied in international trade. Although land isn’t physically being transported or shipped overseas, the land dedicated to producing those goods that do get exported can be considered a telecoupling represented by that trade flow. This type of analysis has been applied to investigating virtual water (D’Odorico et al 2010), virtual groundwater (Marston et al 2015), seafood trade (Gephart and Pace 2015), and embodied nutrients (Leach et al 2012).

While it may be easy to recognize globalization’s impact on our choices, as consumers we often have little reliable information about how specific purchasing habits contribute to or reinforce global inequities, injustices, or unsustainable practices with which we might disagree, especially when strapped for time and money. Although price was considered the overriding factor that we use to make purchasing decisions as consumers, many people in the class also identified priorities related to ethical treatment of people and animals in the production of goods, the durability and quality of goods, and other factors that are linked to global inequalities and sustainability practices. Some new practices and technologies can enable consumers to reflect ethical values in consumption patterns, such as voluntary certification schemes and data-based guidelines.

3. Coupled multi-level networks

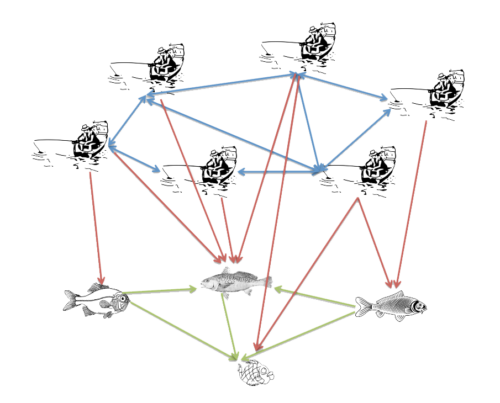

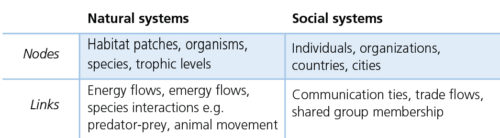

One of the newest frameworks for network analysis attempts to bring together networks of social and ecological systems. Bodin et al. (2016) proposed using multi-level networks to bridge the perspectives from natural and social sciences to analyze complex social-ecological networks.

One example applying this framework is the work of SESYNC postdoc Steven Alexander, who studies social-ecological networks in the Caribbean. He uses this multi-level approach to relate the trophic structure of fisheries to the communication networks of fishermen, to investigate the relationship between governance and ecological outcomes of fisheries.

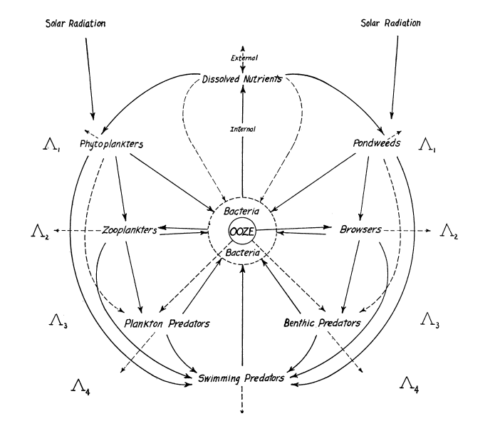

An interesting discussion emerged about the various ways that ecological systems can be conceptualized as networks—what are the discrete entities out in nature? Depending on the question and context, it became obvious that there were numerous ways to think about natural systems as networks, beyond species interactions and trophic levels. In fact, one of the earliest conceptualizations of an ecosystem by limnologist RL Lindemann is certainly representative of a network!

For all three frameworks, it was clear that network structures can be both drivers and outcomes of processes in coupled human and natural systems. Although it takes some work to conceptualize the boundaries, entities, and definitions of each network component, a network perspective is a fruitful avenue for investigating the structure and dynamics of these systems.

References:

- Alexander, S., 2015. The ties that bind: Connections, patterns, and possibilities for marine protected areas. UWSpace. http://hdl.handle.net/10012/10025

- Bodin, Ö., Robins, G., McAllister, R., Guerrero, A., Crona, B., Tengö, M. and Lubell, M., 2016. Theorizing benefits and constraints in collaborative environmental governance: a transdisciplinary social-ecological network approach for empirical investigations. Ecology and Society, 21(1).

- D'Odorico, P., Laio, F. and Ridolfi, L., 2010. Does globalization of water reduce societal resilience to drought?. Geophysical Research Letters, 37(13).

- Jasny, L., Waggle, J. and Fisher, D.R., 2015. An empirical examination of echo chambers in US climate policy networks. Nature Climate Change, 5(8), pp.782-786.

- Gephart, J.A. and Pace, M.L., 2015. Structure and evolution of the global seafood trade network. Environmental Research Letters, 10(12), p.125014.

- Leach, A.M., Galloway, J.N., Bleeker, A., Erisman, J.W., Kohn, R. and Kitzes, J., 2012. A nitrogen footprint model to help consumers understand their role in nitrogen losses to the environment. Environmental Development, 1(1), pp.40-66.

- Leach, A.M., Emery, K.A., Gephart, J., Davis, K.F., Erisman, J.W., Leip, A., Pace, M.L., D’Odorico, P., Carr, J., Noll, L.C. and Castner, E., 2016. Environmental impact food labels combining carbon, nitrogen, and water footprints. Food Policy, 61, pp.213-223.

- Lindeman, R.L., 1942. The trophic‐dynamic aspect of ecology. Ecology, 23(4), pp.399-417.

- Marston, L., Konar, M., Cai, X. and Troy, T.J., 2015. Virtual groundwater transfers from overexploited aquifers in the United States. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 112(28), pp.8561-8566.

- Prell, C. and Lo, Y.J., 2016. Network formation and knowledge gains. The Journal of Mathematical Sociology, 40(1), pp.21-52.

- Prell, C., Sun, L., Feng, K., He, J. and Hubacek, K., 2017. Uncovering the spatially distant feedback loops of global trade: A network and input-output approach. Science of Total Environment. (in press).

Next Post > Talking about Transdisciplinary research in Paris

Comments

-

Natalie Yee 9 years ago

Great job with the visuals and summary of the major concepts! This really brings together nicely what happened in the papers as well as the class discussion. I enjoyed the example of your SESNYC co-worker because it is a clear and real life demonstration of how one can couple together multiple levels of networks and thought to achieve a common goal.

Suzi, I think you make a great point about the convenience factor when it comes to the participation for more sustainable solutions. I personally agree that if the situation were not easily made available, customers would not feel bad about picking the more convenient but less sustainable solution. Even when there are alternatives that try and make the more sustainable option available, the matter of price and convenience are still prominent enough to stop people. For example, free-trade chocolate is available in many grocery stores, but maybe not the bigger name stores. These stores will continue to supply more generic chocolate candy that are not only cheap, but are conveniently located and well-known.

-

V Leitold 9 years ago

In response to the question posed by Suzi, I think that some amount of government intervention might indeed be necessary if we want to ‘nudge’ people in the right direction so that they adopt more environmentally conscious attitudes and/or more sustainable consumer behaviors. This wouldn’t necessarily require restricting people’s choices, rather, the idea is to provide them with sufficiently detailed information so that they can make better-informed choices. As Rebecca has pointed out, sometimes just knowing where a certain product comes from requires actively searching for that information, which only the most dedicated consumer will do. Companies should be incentivized to put informative labels on their products, like the “sustainability rating” in Kelly’s example with the carbon-, nitrogen, and water-footprint of the product indicated on the label, and stores could change the way in which their products are presented to the consumers (e.g. strategically placing the more sustainable goods at eye-level) so that the layout of choices is more conducive to sustainability. (For more on Choice Architecture related to consumer behavior, see this interesting post titled “The ‘Awareness’ Trap”: https://shar.es/1UKKk5)

-

Krystal Yhap 9 years ago

This was an interesting blog post and I think Kelly did a good job including both the readings and our discussion in it. I agree with Rebecca about consumers not having reliable information about how our products and resources are made and what the global and ecological implications of the making of these products are. While I do agree that it would be nice to have information on different companies to see who is participating in unsustainable and unethical practices, I find it hard to believe that the general public would have the time or the desire to use tools such as the Apps like Seafood Watch. I think if more attention was focused on labeling than on technology (like Apps), it would be more successful at grabbing consumers attention and encouraging them to make more sustainable choices. Apps are awesome and there are many useful Apps that have been or are currently being developed, but not everyone has access to such technology and with all the many Apps people have on their phones and tablets its easy to forget about certain Apps. I know I have Apps on my phone that I forgot I even downloaded long ago. Labeling on foods and products would be something that is directly in your face and you don't have to worry about wiping out an App or some other tool.

I like what Noelle said about the coloring, design and creative choice of words/labeling companies use to make a product appear sustainable and make a consumer feel as if they are making a sustainable and ethical choice by choosing that product over other products. This only furthers the need for some tool or labeling system that will help consumer's understand the true impact of these products and distinguish the "fakers" from the "real deal" to make more informed decisions on purchases.

I agree with Suzi, I know I would personally also be willing to give up a little freedom for the sake of the environment and other people that are affected by these decisions but I think it all comes down to what people are willing to give up and what people are willing to pay for.

-

Suzanne Spitzer 9 years ago

I also have a comment about the seafood section of this blog. While I think that it is great that more information about trade and sustainability is being made available to consumers, I am a bit skeptical at the effect that this might have on global practices. I think policy makers and environmental managers need to recognize that most consumers will not have the time or interest to research all of the products they buy- convenience is key. Apps like Seafood Watch could be good for supplying information to those people who do care and informing their conscious behaviors, but how can we influence the behavior of other consumers? Top-down regulations seem to be the most realistic solution for controlling consumption behaviors and trade patterns- If people are not easily able to buy the products that are bad for the environment or that contribute to inequality, then they won't. This alleviates some of the ethical burdens that consumers bear, but I could also see why people might be concerned by the thought of government-controlled selection of available choices. I personally would be willing to give up a little freedom of choice for the good of the environment, or vulnerable communities, but maybe others would disagree? Anyone else have any thoughts on this?

-

Rebecca Wenker 9 years ago

I think you made a great point when you said that although it can be easy to see globalization's impact, "as consumers we often have little reliable information about how specific purchasing habits contribute to or reinforce global inequities, injustices, or unsustainable practices with which we might disagree..."

In many cases, the information just isn't out there, or if it is you really have to go searching for it. I believe that people are realizing this, and are progressively more motivated to change it. Like you showed with the Seafood Watch app, there is an increasing number of databases, labels, apps, etc. that provide information on where your goods come from, and what is involved in making them.

In terms of addressing global trade inequalities, I believe that if more and more individuals make an effort/choice to be aware of unsustainable/cruel practices and avoid them, we could begin to alter the global network.

Side note: This is a cool website where you can look up specific clothing brands, and it gives you information on the business model, material sources, treatment of workers, environmental impact, etc.

https://projectjust.com/research/ -

W.Cruz 9 years ago

Great blog! Same as Rebecca there are other options with the consumption of seafood. The logo of MSC (marine stewardship council) seafood which states that is certified sustainable seafood and responsibly caught but there is other side of it. Industries pay for it so what about artisanal fisheries that cannot afford the certification or big industries like walmart who regulates their fish source? So how can we trust the system when it seems to be corrupted?

-

Noelle O. 9 years ago

Going off what Rebecca mentioned, I agree that there is a lot of effort needed to understand the "true" story behind certain companies (especially large brands). It's a very tricky web of telecoupled resources and land exports. Especially when you consider the global consumer trend of being more "natural" or organic. Take a bottle of shampoo, for example, the way it's designed and with certain colors may make the shampoo appear like it's naturally produced, but the company may still test on animals.

Striving to eat as local and sustainable seafood as possible can definitely drive the cost up. And as Wilmelie said, the MSC certification process (as well as being certified organic by the USDA) are great at bringing awareness for sustainable harvesting practices, but they come at a great cost to the supplier (time and money-intensive processes).

Social network analysis is a great tool to tease out some of actual costs of "virtual" goods, but coupled human and natural systems are inherently complex and hard to grasp the whole picture. Although not perfect, I think the more programs that exist like Seafood Watch and the one Rebecca mentioned, the more informed consumers we be in the market.

-

Rachel E 9 years ago

Great summary of our class discussions Kelly! I think the idea of trying to create a social network of an ecological system is really interesting. Are the nodes specific organisms? or populations? what do the connection represent? I liked the table you made of the ideas we had come up with. Initially when posed this question I thought the connections would be energy. Energy gets introduced into the system via light energy from the sun or from microbes that assemble macro molecules from individual elements. While organisms and wildlife don't necessarily communicate or trade with each other like people, they transfer energy through food webs which keeps the system functioning. Energy initiates with the primary producers and is cycled through all of the members of the ecological system in some way. Each individual therefore connects with another based on how of then transfer energy.

It was interesting to hear the emergy flow perspective from Krystal and the other ideas that people had in the class.

Its too bad we don't have another week to more deeply discuss the ecological side of things. However, it seemed that we all were much more focused on the social interactions and how our actions make impacts on the global scale. -

Killian F 9 years ago

Reading Rebecca and Krystal's posts, I agree that it is important that we make our products and the practices that go into making them more transparent so that consumers can make informed choices. I was wondering though if the general public that is not inclined to research their food in an app would really be affected that much by labeling either. There are a number of different ways that companies promote their products as better for you or for the environments, such as GMO-free, antibiotic free, sustainable, or organic just to name a few. If consumers face a lot of different labels showing different features of their products, particularly if they aren't entirely sure what these labels mean, it might not make that big of a difference on their choices as consumers. In order to make changes in public consumption for the better, there would need to be broader education and communication of environmental issues, beyond small labels or apps.