Got complex problems? Have a transdisciplinary smoothie!

Elisabeth Powell ·Every day we are seeing problems in the news, widespread wildfires in California, rising COVID-19 cases nationwide, intense hurricanes sweeping the coasts, racial injustices, and the list goes on. This is unsettling as the news rarely reports on solutions to these problems. This might be from the lack of media attention to the solutions or these problems do not have current solutions to them, yet. It seems that complex problems require complex solutions and these types of solutions require transdisciplinary science.

Last week in our Environment and Society class, we discussed transdisciplinary science and its use in research. Bill was nice enough to post some videos explaining the concept before we took a plunge into the assigned transdisciplinary literature. Bill translated different disciplinary approaches into something that we all could probably use more of, fruit! He described disciplinary as separate bowls of different fruit, where specific disciplines are separated, multi-disciplinary where different the cut fruit is laid out on the same platter, inter-disciplinary where the cut fruit is mixed into a fruit bowl, and finally trans-disciplinary where all the fruit is blended into a smoothie (Figure 1). The action of blending the disciplines thereby converts the separate fruits into something different. This method could be very applicable to some big complex problems that are on a liquid-only diet.

But how does one get started with the transdisciplinary approach? To me, with environmental science and physical geography background, it is overwhelming to make a smoothie when I am not sure what exact fruits need to be incorporated, nor how they will taste together! Metaphors aside, this idea led to the discussion of the undisciplinary compass designed by Haider et al., 2017 (Figure 2). The compass, like a traditional compass, has four directions but instead of North, East, South, and West, there are four quadrants labeled, a, b, c, and d. This compass is used as a guide for the two crucial competencies: epistemological agility and methodological groundedness. Epistemological agility refers to the ability to take different perspectives from multiple disciplines and effectively communicating and facilitating collaboration among researchers to practice interdisciplinary work (Haider et al., 2017). Methodological groundedness is as having the competence in at least one specific methodology in a scientific area (Haider et al., 2017). The balance between these two competencies is needed for impactful transdisciplinary research and this compass identifies where someone lies within this balance.

The four quadrants of the compass identify different areas of graduate students and other researchers face when traveling toward transdisciplinary science with rigorous sustainability science as the transdisciplinary destination. Quadrant a) (lower left) is labeled conceptual la la land, with low epistemological agility and low methodological groundedness; b) disciplinary immersion with low epistemological agility and medium-to-high methodological groundedness; c) uncomfortable space with medium-to-high epistemological agility; d) basis for rigorous sustainability science with high epistemological agility and high methodological groundedness.

For an interesting exercise, the class members took turns identifying where they saw themselves currently on this compass and where they aspire to be in the future (Figure 2).

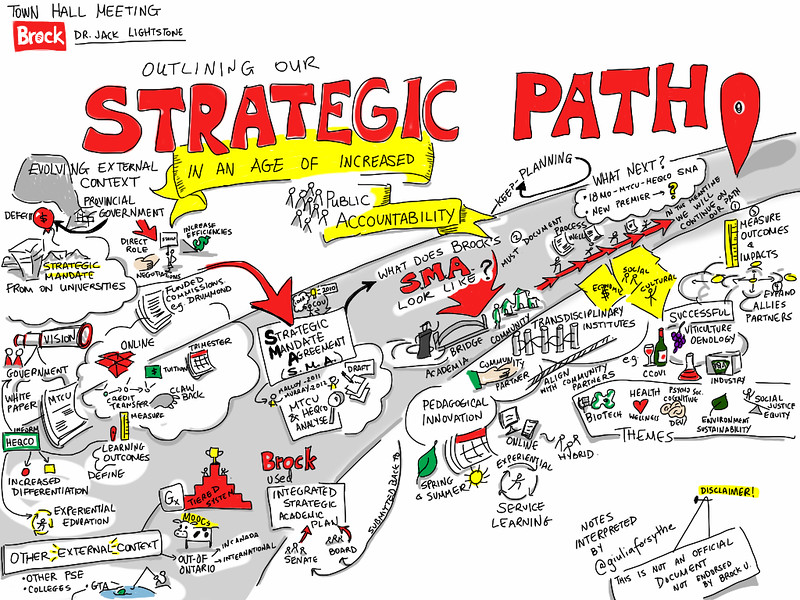

As seen from Figure 2, currently much of the class is between the Uncomfortable space and Conceptual la-la-land. Having low ratios between methodological groundedness and epistemological agility can cause anxious graduate students and researchers as the curation of these skills take time and tenacious effort to build. For the future, the majority of the class aspires to be within the area for the basis of rigorous sustainability science and to carry out different forms of applied research and science communication. But, as we discussed in class, getting to your transdisciplinary destination could take some time as there is no GPS and no estimated time of arrival (Figure 3).

I like this figure as it shows the complexity of solving complex problems. Strategies to solve complex problems require many factors and many players but as Kenny iterated through his experiences in his lecture, it can turn into a big Mess and I think this figure shows that mess.

Moving on from the route to the transdisciplinary destination, let's discuss the utility of this approach. Transdisciplinary approaches can extend the knowledge that is typically bounded by traditional disciplines (Ciesielski et al., 2017). I mean this sounds pretty good because if we go back to the fruit metaphor, I think a strawberry, banana, mango, pineapple, and kale smoothie sounds a little better than just a banana to me! However, to get a tasty smoothie, these fruits need to be ripe, and to get impactful transdisciplinary findings, methodology from different disciplines need to be fully developed and validated. Using transdisciplinary approaches, we might actually ask better questions, therefore get more meaningful results and identify possible interventions (Figure 4) (Ciesielski et al., 2017).

If transdisciplinary approaches are more useful than using just one discipline at a time, then why do we not see it occurring more? Is it because we are in Academia? Do you think we will see it more as time carries on and we face more complex problems than we have ever seen (i.e. sea level rise from climate change, more pandemics)? There is an amazing quote that makes a lot of sense "Science is built up with facts, as a house is with stones. But a collection of facts is no more a science than a heap of stones is a house" - Jules Henri Poincare. I urge students of the class to think about this quote and what it means to them. What do you want to use your research for? Do you think your research could be more impactful using transdisciplinary approaches?

References

Ciesielski, T. H., Aldrich, M. C., Marsit, C. J., Hiatt, R. A., & Williams, S. M. (2017). Transdisciplinary approaches enhance the production of translational knowledge. Translational Research, 182, 123-134.

Disciplinary vs. inter-disciplinary vs. multi-disciplinary vs. transdisciplinary, represented by fruit. (2017). Retrieved October 30, 2020 from /blog/lets-talk-interdisciplinary-dialogues-help-to-operationalize-socio-ecological-systems-resilience-and-sustainability/

Jahn, T., Bergmann, M., & Keil, F. (2012). Transdisciplinarity: Between mainstreaming and marginalization. Ecological Economics, 79, 1-10.

Haider, L. J., Hentati-Sundberg, J., Giusti, M., Goodness, J., Hamann, M., Masterson, V. A., ... & Sinare, H. (2018). The undisciplinary journey: early-career perspectives in sustainability science. Sustainability science, 13(1), 191-204.

Outlining our Strategic Path in an age of increased public accountability (2013). Retrieved October 31, 2020 from https://www.flickr.com/photos/gforsythe/8387531954/in/contacts/