International Coastal Adaptation Perspectives

Heath Kelsey ·

I was lucky enough to be invited to a meeting at Thinkers Lodge in Pugwash, Nova Scotia, in August this year, as part of their continuing commitment to support meetings that address science and societal issues. Our goal for this meeting was to discuss international responses to climate change in coastal communities. Fifteen scientists, practitioners, managers, and indigenous representatives from Australia, Canada, Mexico, the Mi'kmaw Nation, USA, and the West Indies were invited to share their perspectives on coastal climate adaptation. Over three days of meetings, we identified key issues, challenges, and ways forward. We also convened a local meeting to share our discussions with the Pugwash community and to solicit their valuable insights.

We discussed issues related to changing ice conditions in the Arctic, cyclone impacts in Australia, hurricanes in the West Indies, and societal implications of adaptation in the USA. One issue that came up frequently was around the challenge of coastal erosion. Erosion of coastal land is a nearly universal issue affecting homes, agricultural areas, and urbanized areas in coastal areas worldwide. We heard about coastal erosion in Australia, Canada, and the West Indies. This reflects IAN’s experiences: Erosion is a priority issue in many (most?) of the coastal communities we work with globally.

Although some key issues (like erosion) were commonly observed, a key takeaway from our discussions was that coastal adaptation issues and strategies are locally specific. The need for adaptation is widespread, but every location has unique challenges related to changing coastal conditions, so relevant and useful adaptation strategies are, and will continue to be, different in different places. Every location has different physical features, and locally variable relative sea level rise, storm frequency, air and water temperature, and precipitation patterns. Even areas that are relatively close together may have very different needs. For example, as local community members pointed out, the Bay of Fundy in Nova Scotia experiences 16.8 meter tides, while the nearby Gulf of St. Lawrence in the same county has smaller tides (less than 2 meters) and different features and uses. Farther north, changing ice formation and conditions affect the safety and mobility of indigenous communities that rely on ice for transportation. While it may be tempting to try to identify climate adaptation responses that are broadly applicable, there are no “one-size-fits-all” solutions, only locally relevant strategies (thank you Rosemarie Lohnes for that distinction!).

On the last day of our meeting, we experienced some of the unique settings in the Canadian maritime coast first hand through field visits to Tidnish Dock Provincial Park, and Baie Vertre contrasted with Chignetco Bay (upper Bay of Fundy) at Aulac in New Brunswick. We saw ongoing shoreline erosion and multiple types of erosion and flood control strategies. Each place we visited highlighted important differences in adaptation priorities, as well as the options for addressing them. Special thanks to Dr. Jeff Ollerhead for the insightful history and context for our journey!

Another theme of our discussions seemed especially relevant in light of current support for science and the use of scientific evidence in environmental policy. All of our discussions started from a foundation of scientific inquiry, which provided insights to problems and potential strategies. Some of those strategies might be convenient and easy, but many will be inconvenient, difficult, or expensive. Even when solutions are elusive and responses are difficult, I find a certain reassurance that scientific knowledge can help us describe what’s happening and what we might do about it. Even if we choose not to use it, the science is there regardless. I can’t describe why that provides me comfort, but it does.

In the coming weeks, the group will co-create a statement that captures what we learned together and how we will continue in the future. I sincerely look forward to continuing this work.

As we went through our discussions, I also thought about the significance of the venue and its link to science and society. In fact, Thinkers Lodge has an impressive history. In 1955, shortly before his death, Albert Einstein, Bertrand Russel, and nine other prominent scientists issued what has become known as the Russel-Einstein Manifesto. At the height of the Cold War, the Manifesto challenged scientists from the east and west to meet to promote peace and prevent the use of nuclear weapons in war. The first such conference was held at Thinkers Lodge in July 1957, sponsored by Pugwash native, industrialist Cyrus Eaton. That first meeting included scientists from the USSR, Japan, UK, USA, Canada, Australia, Austria, China, France, and Poland. It is truly remarkable that this group was able to meet face-to-face at all during the Cold War, especially to discuss issues as sensitive as nuclear weapons. Outcomes from this first meeting set the stage for the Limited Test Ban Treaty of 1963, which banned nuclear weapons testing in the atmosphere, underwater, and in space.

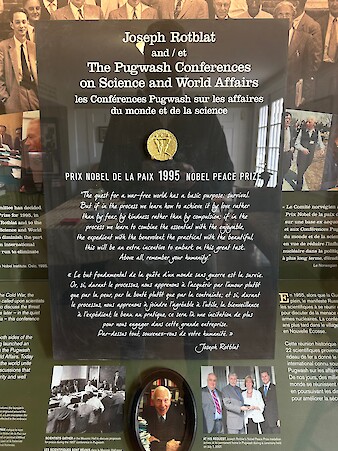

The 1995 Nobel Peace Prize was jointly awarded to the Pugwash Conferences on Science and World Affairs and Joseph Rotblat, who was one of the signatories of the Manifesto, for efforts that began at that 1957 meeting. Subsequent meetings have occurred regularly at different venues worldwide, and the Lodge has become iconic as a symbol of peace and scientific reflection. The award is on display at the Thinkers Lodge lobby. It was inspiring to be have our meeting in such a storied location.

Special and heartfelt thanks to Teresa Kewachuk and all of the Thinkers Lodge staff and volunteers who made our visit so comfortable, fun, and delicious! We were treated to family recipes for lobster rolls, seafood chowder, and a host of other local delicacies, all delicious and special. Thank you for making our visit so delightful. And, of course, thanks to Drs. Don Forbes and Gavin Manson for organizing such a great week.

About the author

Heath Kelsey

Heath Kelsey has been with IAN since 2009, as a Science Integrator, Program Manager, and as Director since 2019. His work focuses on helping communities become more engaged in socio-environmental decision making. He has over 15-years of experience in stakeholder engagement, environmental and public health assessment, indicator development, and science communication. He has led numerous ecosystem health and socio-environmental health report card projects globally, in Australia, India, the South Pacific, Africa, and throughout the US. Dr. Kelsey received his MSPH (2000) and PhD (2006) from The University of South Carolina Arnold School of Public Health. He is a graduate of St Mary’s College of Maryland (1988), and was a Peace Corps Volunteer in Papua New Guinea from 1995-1998.