Let’s Start By Talking About Ecosystem Services

Bill Nuttle · | Learning Science |We all have a stake in sustaining functional ecosystems

When ecologists and economists began talking about ecosystem services in the 1990s it was to make a stronger argument for restoring and preserving natural systems. The idea that nature provides the life-support system of the planet, cleaning and recycling the air and water and providing us with food and raw materials, motivated the environmental activists of the 1960s and 70s. That idea was fading in the popular consciousness in the 1990’s, and during the economic boom years it made sense to take a more business-like approach in environmental issues. But there is more to the concept of ecosystem services than just making a better argument for protecting nature. Talking about ecosystem services gets people thinking about their goals and values for the ecosystem, and that can change the nature of the discussion.

Ecosystem services are the benefits that people get from the environment. Healthy ecosystems provide a higher level of services than degraded ecosystems. EPA measures progress toward the restoration of Chesapeake Bay in terms of their Total Maximum Daily Load (TMDL) criteria, essentially putting the Bay on a “nutrient diet.” What most people will see, however, is an increase in the benefits that a less polluted bay is capable of providing - benefits like better fishing, swimming, and boating and improved property values. For example, research has shown that there is a link between the rate of fish caught by recreational fishers and water quality in the Chesapeake Bay, as measured by dissolved oxygen and high concentrations of algae (Lipton and Hicks 2003). These aspects of water quality will improve with compliance with the TMDL regulations, leading to better fishing in the Bay.

Ecosystem services have value, which can be measured in various ways. For the authors of “Natural Capital” (Kareiva et al. 2011), the fact that we can quantify ecosystem services expands the information available to managers in making tough decisions needed to protect the environment. Critics of using ecosystem services in this way point to problems in assigning a dollar value to ecosystem services (Wegner and Pascual 2011). Both sides agree that estimating the values of ecosystem services is useful as a guide to decision-making, but it is not the whole story. Scientific models and benefit-cost analysis do not substitute for the messy process of engaging stakeholders, forging a shared vision of the ecosystem, and articulating the possibilities for the future.

Calculating the economic value of ecosystem services has proven useful in the Florida Keys. The Florida Keys offers visitors access to a unique sub-tropical coral reef and coastal marine wilderness. Growing evidence pointed to inadequate treatment of residential wastewater as a threat to the pristine waters surrounding the Keys. In the 1990s, residents of the Keys faced a difficult decision on whether to spend about $1 billion to install centralized sewage treatment, a proposal that also ran counter to the laid-back, independent Keys’ lifestyle. An economic study to evaluate ecosystem services that support the tourism industry estimated the total asset value of the Keys’ pristine waters between $18.2 billion and $30.4 billion (Leeworthy and Bowker 1997). Looked at in this way, the $1 billion price tag for improved wastewater treatment is a reasonable amount to pay to protect the environment and the economy.

Talking about ecosystem services also shifts the discussion about how to best protect the environment. We can talk about limiting impacts of human activities on the environment, but not about eliminating impacts entirely. Impacts cannot be avoided without also sacrificing the benefits people obtain from the ecosystem. Food must be harvested, and even obtaining lower-impact cultural benefits, such as education, involves disturbing the natural ecosystem. Sustaining ecosystem services requires managing trade-offs and competition between different goals and values that people have for use of the environment.

The way that ecosystem services changes the conversation was revealed to me through my participation in the MARES (MARine and EStuarine Goal Setting) project in South Florida. The objective of the MARES Project is to identify important components of the South Florida coastal marine ecosystem so that people can sustain the valuable services it provides. The project convened several workshops to gather information about how the ecosystem works. One of the unique challenges we faced was figuring out how to include human activities in the coastal marine environment into our conceptual ecosystem model. The Miami urban area is one of the most densely populated areas in the US, and the vast majority of the region’s over 6 million residents live within 10 miles of the coast.

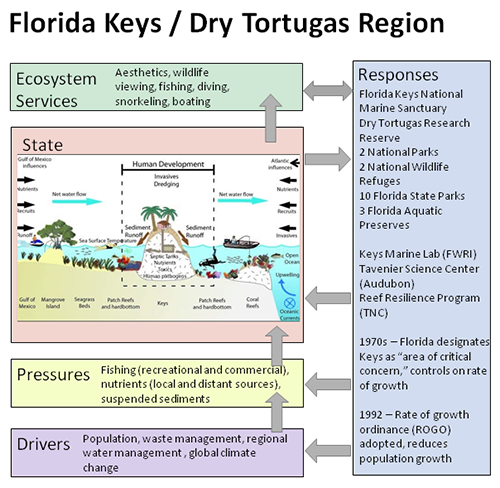

The problem was that we did not know where to start. Project organizers adopted the DPSER framework to organize the conceptual model, because this solved the problem of how to include people. Previous ecosystem models in South Florida used the Pressure-State-Response framework, which is built around the more or less linear, cause-and-effect relationship between factors driving change in the ecosystem, i.e. Pressures, and the changes that result, i.e. Responses. With this framework, the natural place to start is by making a list of Pressures. However, the DPSER framework incorporates feedback. “Response” in the DPSER framework captures people’s response to changes in the State of the environment, and this includes the actions designed to modify the factors causing change in the ecosystem, the Drivers and Pressures. There is no obvious place to start, because the DPSER framework is circular in nature.

Participants in the first workshop of the MARES project had the insight to begin with ecosystem services, the E in DPSER, and work through elements of the model from there. Because not everyone was familiar with the concept of ecosystem services, the opening discussion focused on attributes that people care about in the South Florida coastal marine environment - like clear water, lots and a large variety of fish and marine water birds, and healthy coral reef communities. When we were finished, the workshop had produced a different view of the ecosystem than anyone anticipated.

The models produced by the MARES workshops provide a more balanced picture of how people interact with the ecosystem. Previous modeling efforts that people had participated in, based on the Pressure-State-Response framework, produced models that focused on all the things that people feared were going wrong with the environment. Ecosystem services can be negatively affected by pressures caused by some human activities, but people are also engaged in activities intended to mitigate harm and enhance conditions. It’s not a choice between either protecting the environment or benefiting the economy. Problems arise from incompatible, competing uses of the ecosystem. People may have different goals and values when it comes to what parts of the environment they care about most, but we all have a stake in sustaining functional ecosystems.

References:

Kareiva, P., H. Tallis, T.H. Ricketts, G.C. Daily, and S. Polasky, 2011. Natural Capital: Theory and Practice of Mapping Ecosystem Services. Oxford University Press, Oxford.

Leeworthy, V.R., and J.M. Bowker, 1997. Linking the economy and environment of Florida Keys/Florida Bay: Nonmarket economic user values of the Florida Keys/Key West. National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration/U.S. Department of Agriculture Forest Service, 41 pp.

Lipton, D.W., and R.W. Hicks, 2003. The Cost of Stress: Low Dissolved Oxygen and the Economic Benefits of Recreational Striped Bass Fishing in the Patuxent River. Estuaries 26: 310–315.

Wegner, G. and U. Pascual, 2011. Cost-benefit analysis in the context of ecosystem services for human well-being: a multidisciplinary critique. Global Environmental Change 21:492-504.