Looking through the Lens of Environmental Justice

Katrina Kelly ·On April 16, 1963, from a Birmingham jail cell, Dr. Martin Luther King penned a letter1 containing the often quoted, "Injustice anywhere is a threat to justice everywhere." King further elaborated in this discourse his understanding of the boundarylessness of injustice and how that, which is accepted unchallenged normalizes into a standard which then proliferates throughout a system becoming a defining structure2 within which society develops, such as we have seen throughout America's history3. Five decades later, the struggle for a racially just America continues, though the dimensions of which are expanded and updated to mirror current equity issues such as healthy food access, the right to clean air4, safe drinking water5, freedom from violence, gender/LGBTQ equality, and the effects of climate change.

In 1994, former President Bill Clinton signed Executive Order 129896 to enhance legal recourse against violations of environmental justice. Our Environment and Society class discussion on November 19, 2020, focused on the latter, but as we learned from our guest lecturer, Dr. Christy Miller Hesed, environmental justice is not a singular narrative but a collective lens for quantifying, determining, and understanding the experience of injustice for disparate groups in America. It is also a multidisciplinary, formalized, and/or grassroots platform for collective action against injustice across societal lines. This is the baseline from which environmental justice theory begins.

Environmental justice7 may also be thought of as a means of examining both the outcomes and the related origins of inequality through which a framework of change can be cooperatively constructed and executed. The University of Michigan's 2020 Environmental Justice Fact Sheet8 describes environmental injustice in terms of, for example, greater exposure to pollution, loss of land, property or rights to resources, or limited access to environmental services and delineates five (5) categories in which marginalized communities may experience these negative impacts: (1) the built environment, (2) through limits of food access9, (3) energy poverty, (4) materially, and (5) climate change10 impacts. What this report also notes is the inextricable link between environmental justice and sustainability.

Dr. Hesed engages environmental justice framework in the context of climatic change in the Hesed and Ostergren article, "Promoting climate justice in high-income countries: lessons from African American communities on the Chesapeake Bay," 11 recognizing the human and natural

"Hurricane Sandy press conference Ocean City Maryland" by MDGovpics is licensed under CC BY 2.0

world as dynamic feedback systems with responses to events having ripple effects throughout and results in that may be delayed or immediate, finite, or cumulative. The way these manifest often combine to disproportionately impact already vulnerable populations12. In the Eastern Shore region of Maryland, historic communities and structures are threatened by sea-level rise, marsh migration, and resource politics that have limited their material ability to respond to climate change as well as their access to take part in solutions to address managing their and the natural environment in which they live.

In the Hesed and Ostergren article, environmental justice is defined in terms of the inherent injustice of climate change effects and the three (3) practical theories through which it is understood. The first of these is the theory of distributive Justice which moves beyond the concept of equality or equal distribution to one of equity or compensatory distribution. What does this mean in practice? Imagine you have two separate and unaffiliated people who are hungry, and both are provided with a can of beans that can only be opened with a can opener. If one person has a can opener and the other does not, the equally distributed resource is still unequal because the recipient lacking the appropriate tool to access the food is unable to benefit from it. The concept of equity would compensate for this pre-existing inequality and provide the resource (the can of beans) and the necessary tool (a can opener) to maximize the provision.

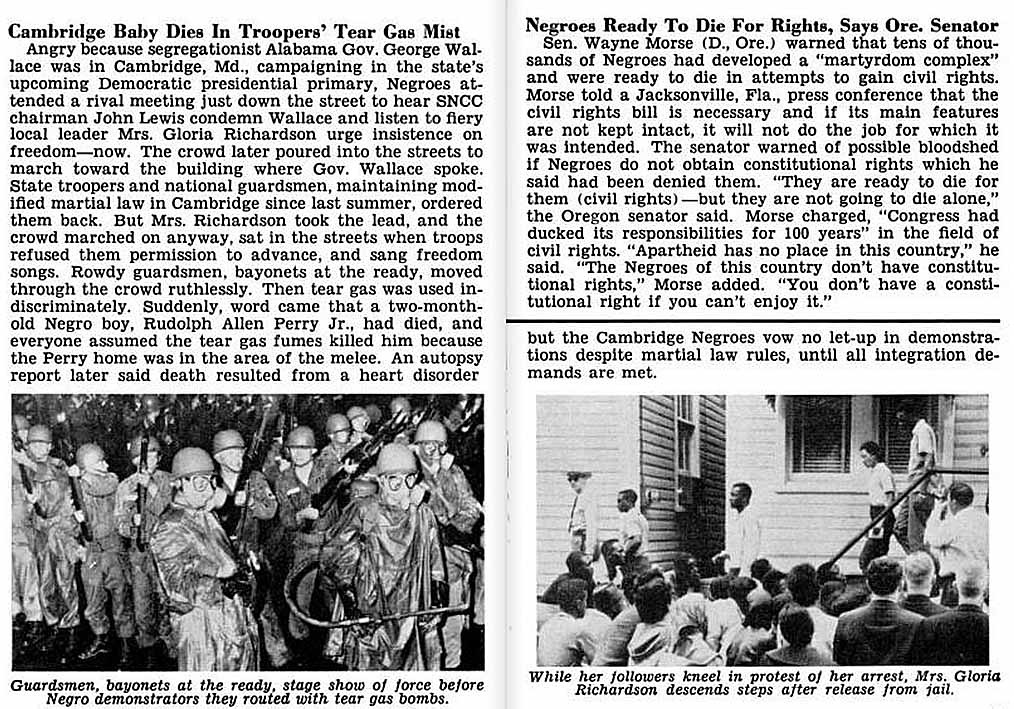

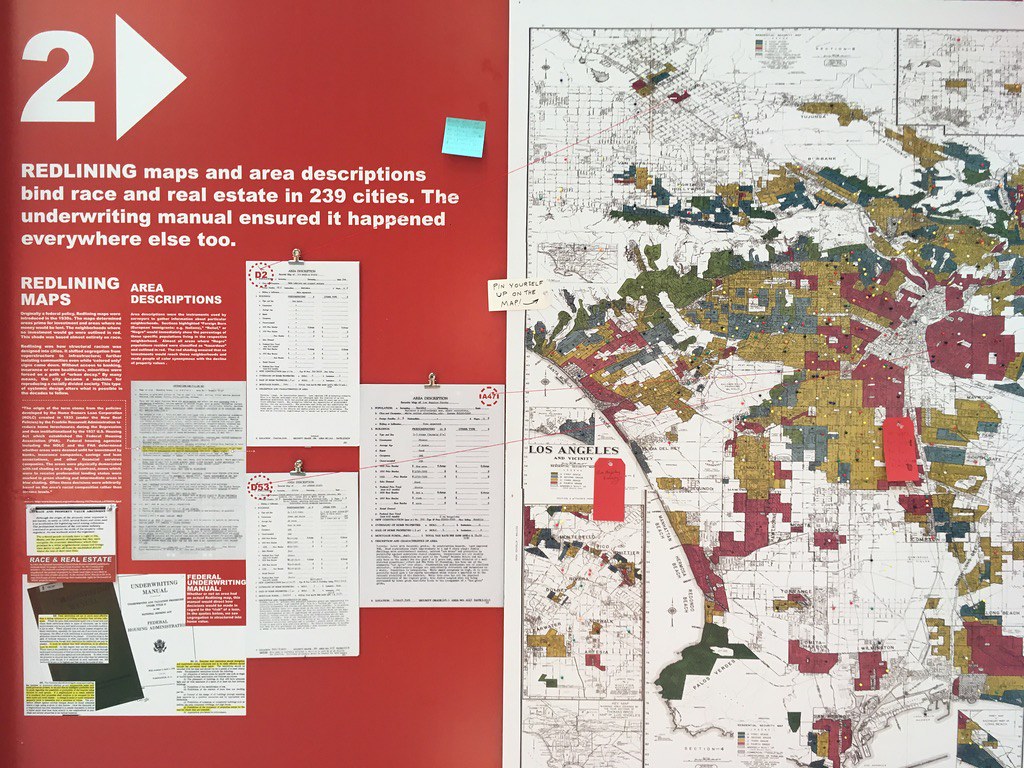

The second of these is the theory of procedural justice which is approached deliberatively or in other words, consideration of a justice issue through established processes (e.g., jurisprudence, Habermas' Ideal Speech Situation, Foucault's theory, etc.) or acquisition of justice by other means, for example, through a disruption of the conventional pathways and norms. Given the historical failures of the American system to reliably reform its own systemic biases, BIPOC (Black, Indigenous, people of color), but particularly Black communities have garnered victories through alternative approaches such as the grassroots community resistance and activism referenced in the Bullard and Johnson13 piece, in civil (e.g., boycotts, sit-ins, etc.) and uncivil forms of disobedience (e.g., rioting or uprising, depending upon perspective). These movements emerge from and respond to what Bullard and Johnson define as (1) unequal enforcement of environmental, civil rights and public health laws; (2) differential exposure of some populations to harmful chemicals, pesticides, and other toxins; (3) faulty assumptions in calculating, assessing, and managing risks; (4) discriminatory zoning14 and land-use practices; and (5) exclusionary practices15 that prevent some individuals and groups from participation in decision making or limit the extent of their participation.

The final of these is the theory of climate justice which recognizes the uneven features of climate change that often result in disproportionate disadvantages for already disadvantaged and/or disenfranchised populations. This theory acknowledges that (1) not everyone is equally responsible for causing climate, (2) not all people are equally vulnerable to the impacts of climate change, and (3) not everyone is equally empowered to participate in the decision-making processes that will affect how limited adaptation resources are utilized and distributed. Relevant to this is Williams' argument in the article, "Environmental injustice in America and its politics of scale" 16 that while it is most often low-income and/or communities of color that are designated for hazardous sites, commercial entities counter this with market-based metrics that place the burden of proof otherwise back on the target community.

As this field of scholarship evolves, traditional notions of injustice will require re-examination. As observed by Wright in the article, "As Above, So Below: Anti-Black Violence as Environmental Racism"17 formalized concepts of racially situated environmental threats have focused on air quality, soil toxicity, contaminated water, etc. He maintains, however, mortal threats such as police brutality and hate crimes are equally prevalent threats to Black and other marginalized communities, often with limited recourse to justice as evidenced historically and recently with the killings of Ahmaud Abrey, Breonna Taylor, and George Floyd. In response, Wright suggests considering how the reality of "gratuitous violence and death" of Black people constitutes a geographic and environmental threat and should also be included as an expression of environmental racism.

Similar expansion on environmental justice thought borrows from political ecology, gender and sexuality studies, critical race theory and critical race feminism, and ecological feminism, and others to allow for intersectional interpretations of environmental justice that may arise from other definitions of the vulnerability of groups. The scholarship of Pellow, "What is critical environmental justice?" 18 defines in a four-pillared framework, Critical Environmental Justice Studies which is noted as the first pillar which recognizes that social inequality and oppression in all forms intersect; the second pillar focuses on the role of scale in the production and resolution of environmental injustices; the third pillar holds the view that social inequalities are deeply embedded in society and reinforced by state power; and the fourth pillar centers on the concept of indispensability, an acknowledgment of John Marquez' concept of "racial expendability" of black and brown bodies in the eyes of the state and its constituent legal system." The practice of Critical Environmental Justice studies includes the core work of countering white supremacist ideology and human dominionism and their role in the reproduction of injustice centered on devalued otherness.

The tools of environmental justice can be applied in such conflicts to counter this added exposure in a way that reapportions responsibility. This rebalancing is an active and evolving process, requiring calibration at various points, as noted in the Van Dolah work referencing the socio-ecological systems (SES) approach to examining disconnects between prioritization of community interventions and resource allocation19. The SES paradigm requires resource managers and other practitioners to expand their evaluation of resilience to consider natural and human interactions within a system, with the health of both included in its definition.

Environmental justice work is the continuation, the expansion of civil rights20 and anti-racism work. In the wake of this past year of peaceful and violent protests, high profile police brutality, inequities laid bare by the COVID-19 pandemic, what we should all know now is that injustice is everyone's problem as Bill Dennison alluded during our discussion. This painstaking but important work can seem, as Kenny Rose stated, like "death by a thousand cuts" having only minute impacts on the systemic issues that prevail. Ultimately, the effects of climate change are an evolving part of our human system and natural system and just as each continent is connected by waterways across the planet, SLR will spill over into the lives of coastal and inland communities alike in yet unforeseen ways. In response, we can choose, in the smallest of ways, in our professions, in our communities, in our intentions, to, as Gandhi declared, " live the changes we want to see in the world." Herein lie the challenge and the opportunity.

CITATIONS

1. King, Jr., M. L. Letter from Birmingham Jail (1963, April 16) [Abridged]. Retrieved November 29, 2020, https://liberalarts.utexas.edu/coretexts/_files/resources/texts/1963_MLK_Letter_Abridged.pdf

2. Beres, D. (2019, January 30). How LBJ Foresaw the Election of Donald Trump. Retrieved November 30, 2020, from https://bigthink.com/21st-century-spirituality/lbj-lowest-white-man

3. Biewen, J. (2020). The lie that invented racism | John Biewen. YouTube.com. Retrieved 29 November 2020, from https://youtu.be/oIZDtqWX6Fk

4. Chase, B and Judge, P. (2020, August 03). Interactive Map: Pollution Hits Chicago's West, South Sides Hardest. Retrieved November 30, 2020, from https://www.bettergov.org/news/interactive-map-pollution-hits-chicagos-west-south-sides-hardest/

5. Sisk, T. (2020, March 10). A lasting legacy: DuPont, C8 contamination and the community of Parkersburg left to grapple with the consequences. Retrieved November 30, 2020, from https://www.ehn.org/dupont-c8-parkersburg-2644262065.html

6. "Summary of Executive Order 12898 - Federal Actions to Address Environmental Justice in Minority Populations and Low-Income Populations." EPA, Environmental Protection Agency, 23 July 2020, www.epa.gov/laws-regulations/summary-executive-order-12898-federal-actions-address-environmental-justice.

7. Berardelli, J. (2020). "Two different realities": Why America needs environmental justice. Cbsnews.com. Retrieved 29 November 2020, from https://www.cbsnews.com/news/environmental-justice-movement-climate-change-racism-peggy-shepard/

8. Environmental Justice Factsheet | Center for Sustainable Systems. Css.umich.edu. (2020). Retrieved 29 November 2020, from http://css.umich.edu/factsheets/environmental-justice-factsheet.

9. Brones, A. (2018, May 15). Food apartheid: The root of the problem with America's groceries. Retrieved November 29, 2020, from https://www.theguardian.com/society/2018/may/15/food-apartheid-food-deserts-racism-inequality-america-karen-washington-interview

10. UCS Conversation: Connecting Faith, Climate, and Justice. (n.d.). Retrieved November 30, 2020, from https://secure.ucsusa.org/onlineactions/XZILm3qCskCkTlUtbnrFwA2?contactdata=k3gtwk0LuNz0i7PzcAP1CnMn3yvI%2F%2F+FjWoSo0f8QrYNLSwbW45al7f1jkyb2OJ3

11. Hesed, C. D., & Ostergren, D. M. (2017). Promoting climate justice in high-income countries: Lessons from African American communities on the Chesapeake Bay. Climatic Change, 143(1-2), 185-200. doi:10.1007/s10584-017-1982-4

12. EJAtlas | Mapping Environmental Justice. Environmental Justice Atlas. (2020). Retrieved 29 November 2020, from https://ejatlas.org/

13. Bullard, R. D., & Johnson, G. S. (2000). Environmentalism and Public Policy: Environmental Justice: Grassroots Activism and Its Impact on Public Policy Decision Making. Journal of Social Issues, 56(3), 555-578. doi:10.1111/0022-4537.00184

14. Jackson, K. (1980). Federal Subsidy and the Suburban Dream: The First Quarter-Century of Government Intervention in the Housing Market. Records of the Columbia Historical Society, Washington, D.C., 50, 421-451. Retrieved November 28, 2020, from http://www.jstor.org/stable/40067830

15. U.S. Census Bureau (2020). Gaps in the Wealth of Americans by Household Type in 2017. The United States Census Bureau. Retrieved 29 November 2020, from https://www.census.gov/library/stories/2020/11/gaps-in-wealth-of-americans-by-household-type-in-2017.html?s=03.

16. Williams, Robert W. (1999). Environmental injustice in America and its politics of scale, Political Geography, Volume 18, Issue 1. Pages 49-73, ISSN 0962-6298, https://doi.org/10.1016/S0962-6298(98)00076-6.

17. Wright, W. J. (2018). As above, so below: anti-black violence as environmental racism. Antipode, (2018). https://doi.org/10.1111/anti.12425

18. Pellow, D. N. Das, S. P. (2019). What is Critical Environmental Justice? International Sociology, 34(2), 231-233. https://doi.org/10.1177/0268580919831637a

19. Van Dolah, et al. (2020) Article: WELA-D-19-00284R1. University of Maryland Department of Anthropology.

20. Profita, C. (2020). NPR Choice page. Npr.org. Retrieved 29 November 2020, from https://www.npr.org/2020/11/21/936850821/climate-justice-fund-counters-centuries-of-underinvestment

About the author

Katrina Kelly

Katrina Kelly is a first year master’s student of Environmental Science in the Marine Estuarine Environmental Sciences program at the University of Maryland Eastern Shore, Department of Natural Sciences. She is advised by Dr. Joseph Pitula. She previously worked and assisted in research involving oyster restoration for water filtration functioning in the Chesapeake Bay with the Healthy Harbor Initiative in Baltimore City, and assisted with the Urban Pest Project with Drs. Loren Henderson and Dawn Biehler at UMBC, studying the social impact of bed bug infestations. She is interested in sustainable urban development and planning as well stormwater management/flooding impacts on lower-income and historically marginalized communities.