Make Some Noise with Data & Sound Science

Anikka Fife ·In the realms of environmentalism, we often suffer from the proposition of how do “we” affect the environment? Historically, it has taken drastic effects from the environment for humans to contemplate how their health is affected by the natural world. As this understanding has progressed we realize that our society has caused negative impacts on the environment and that these impacts can lead right back to us. To make matters worse they might be leading back to some more so than others. Unfortunately, those least responsible for the environmental degradation are experiencing the worst of it.

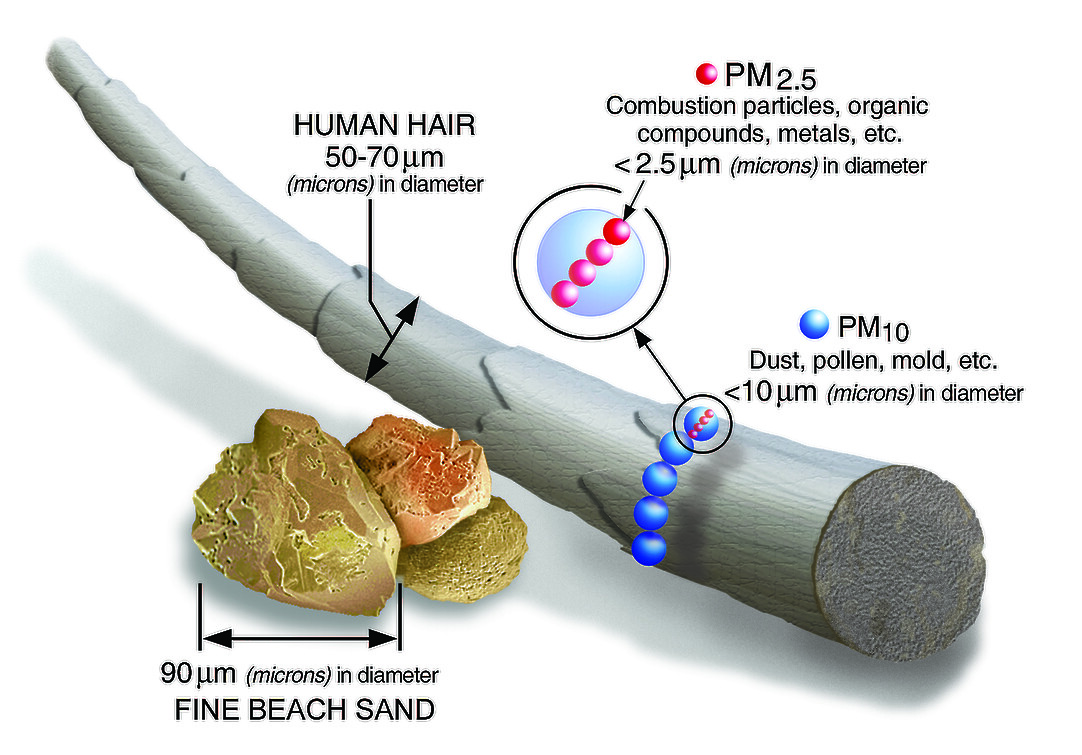

A prime example is air pollution from the development of industrialization and the increase of urbanization. As wildfires set out across the western United States, a particle known as PM 2.5 has attracted attention concerning public health. However, the particle comes from a variety of other sources like industrial processes, fossil fuels, and construction sites. It is a fine, inhalable particle affecting ecosystems and public health.

Unfortunately, the majority of the communities are urban residents, low-income households, and minorities who face the harms of these pollutants and remain under-recognized in these disparities (Looney et al). With marginalized populations more likely to experience the effects of PM 2.5 compared to white populations and higher status neighborhoods, the air pollutant is a public health concern and an environmental injustice.

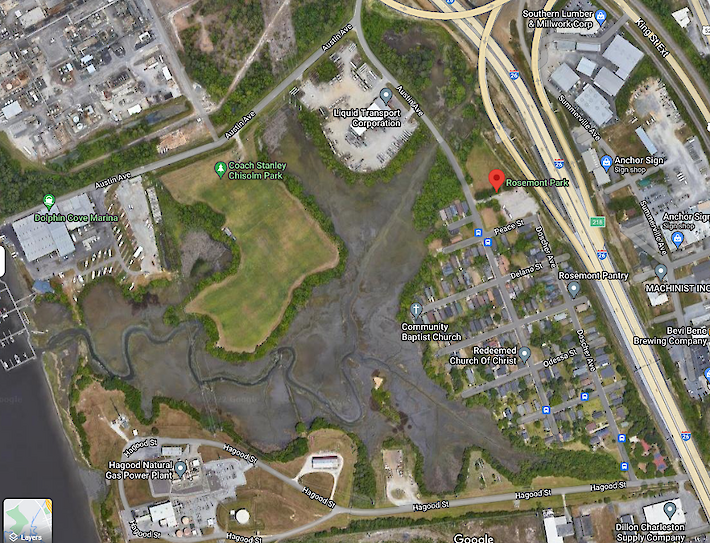

Guest lecturer Dr. Porter spoke to our Coastal Environment and Community Health class earlier this September. From the University of South Carolina, he has led a team of students, multiple affiliate organizations, government agencies, and most importantly in this case, the local community. This “bottom up” approach has allowed for a local community known as Rosemont in Charleston, South Carolina to synthesize environmental impacts concerning their public health and the isolation of their community by Interstate 26. For the Rosemont community it’s much more than just air pollutants. The environment has also burdened them with flooding and standing water leading to contaminants from industrial complexes along the I26 ramp expansion.

Since the highway nestled between the community, and industrial pollutants contaminated the water and air, the community has been tackling an instance of environmental injustice. Working with the university, Rosemont has been able to collect data that monitors the environment and the impacts experienced from government inaction.

When hurricane Ian struck the community, residents battled flooding and standing water hazards. Through this crisis, the community was able to take the data from their existing monitoring systems and form potential recommendations. These recommendations aimed to improve the environment of Rosemont, the quality of life for residents, and furthered the need to improve the data methods to better capture the experienced crises.

The community partnerships developed allowed for a major impact not only for the Rosemont community, but for everyone involved. Those in the university sector and multi-organizations obtained sound citizen science to expand their own understanding of environmental issues as they affect the public and local communities. It also serves as an example of collaboration so that other communities like Rosemont, that might be facing similar issues, feel empowered to fight environmental injustices.

“They have gotten funding from the city of Charleston; they’ve gotten additional funding from the EPA and its become a role model for what communities can do when they decide to remove primarily the use of emotions from the decision making process and work to use sound science and data. They empower themselves to use sound science and data to make noise.” Dr. Porter. Source: Dr. Porter

As coastal communities face challenges through environmental change it's important that monitor systems remain in place and continue to expand alongside such changes. Citizen science and input enriches our understanding of public health, and empowers those under-recognized communities. Collaboration between those living in the community and those willing to assist with regulation fosters improvements. All of which help to create a healthy community and environment.

Sources:

- Dennis Jr., R. C. (2022, December 29). Rosemont residents solving their own flooding issues on Charleston’s Upper Peninsula. The Post and Courier. https://www.postandcourier.com/news/rosemont-residents-solving-their-own-flooding-issues-on-charlesons-upper-peninsula/article_dd98f2c8-8135-11ed-81b7-939a70787fa0.html?mode=nowapp

- Environmental Protection Agency. (n.d.). Particulate Matter (PM) Basics. EPA. https://www.epa.gov/pm-pollution/particulate-matter-pm-basics

- Emerson, A. (2019, October 10). Charleston’s historic Rosemont community impacted by environmental issues. WCIV. https://abcnews4.com/news/local/charlestons-historic-rosemont-historically-afflicted-with-environmental-issues

- Looney, Erin and Hallum, Shirelle and Chupak, Anna and Porter, Dwayne and Kim, Ye Sil and Kaczynski, Andrew T., Examining Longitudinal Trends in Fine Particulate Matter (Pm2.5) Exposure According to Social Vulnerability in South Carolina. Available at SSRN: https://ssrn.com/abstract=4875655 or http://dx.doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.4875655

- Porter, Dwayne. (2024, September 11). Empowering Communities to “Use Data and Sound Science to Make Noise!” [Slideshow]. University of South Carolina.

About the author

Anikka Fife

Anikka is from Kent Island, MD and graduated from Salisbury University with a B.A. in Communications-Media Production and a B.A. in Environmental Studies. Her interdisciplinary interests focus on combining her artistic skill sets in media production with topics surrounding environmental science. Anikka has experience in creating educational outreach materials, documentaries, and has directed several field projects concerning the health of the Chesapeake Bay and its communities.

Currently, she is a graduate research assistant at Horn Point Laboratory and is a member of the Innovation Team at the Global Nitrogen Innovation Center for Clean Energy and the Environment. Anikka's research focuses on environmental sociology topics such as behavioral analysis of farmers located on the Chesapeake Bay Watershed, their nitrogen use efficiency and synthesizes the socio-environmental challenges or opportunities regarding green technology innovation such as green nitrogen for farmers.