Nature and Culture as Star-Crossed Lovers: Can we have one without the other?

Faith Taylor · 11 commentsBy: Faith Taylor

This week Dr. Paolisso referred to culture as the lens through which we view nature and honestly I didn’t think too much of this statement until I sat down to write this blog post. If culture is the lens through which we view nature, I think that lens is more like a kaleidoscope than a pair of glasses. When we view something through a kaleidoscope the entire image is altered into lines, colors, and shapes that are beautiful, but they do not make sense without the assistance of the kaleidoscope itself. In fact, the word kaleidoscope is derived from Greek words meaning “beautiful” and "to view”1.

All of the authors this week sought to look at the relationship between culture and nature through their own lens in hopes of better understanding the role that culture does or does not play when it comes to human interactions in the natural world. We were tasked to first read two chapters in William Cronon’s edited volume Uncommon Ground: Rethinking the Human Place in Nature, then to read Roy A. Rappaport’s article “Ritual Regulation of Environmental Relations among a New Guinea People” and then finish off the readings with Aletta Biersack’s article “Introduction: From the ‘New Ecology’ to the New Ecologies”. Since I’m a rebel, I did not read them in this order, but I will discuss them in this order in an attempt to make up for my rebel behavior.

Uncommon Ground: Rethinking the Human Place in Nature is a collection of essays written by professionals of many disciplines, each who provide a unique take on the way humans interact with the natural world. Throughout Cronon’s introductory chapter he describes the various views that humans can have about nature, such as “nature as a moral imperative,” “nature as a commodity,” and “nature as contested terrain”2. Although there were many things that struck me as interesting in the two chapters we read, I would like to further examine the outlooks of “nature as Eden” and “nature as a virtual reality”.

The garden of Eden is a reference to the bible’s book of Genesis. According to the bible, God made the garden of Eden so that the first humans, Adam and Eve, could live there. In this Eden, all of Adam and Eve’s needs are met as long as they do not eat the forbidden fruit from the tree of knowledge3. This concept of “nature as Eden” stuck with me because there is a romanticized feeling of knowing that God himself created a landscape just for us to be able to use and enjoy as long as we do not take advantage of it. I think this might have been what Dr. Paolisso meant when he talked of poetic language. The idea of nature as Eden reminds me of an oasis in the middle of a desert or a picnic outside with vegan pizza that actually tastes good, but others' "Eden" is not the same as mine. Cronon describes the problem with the "nature as Eden" concept: “Trouble surfaces only when, as so often happens, one person’s Eden comes into conflict with another”2. The trouble in Eden reminds me of when my neighbor trimmed the tree on my mom’s yard without her permission. To my neighbor, the tree branches were disrupting the Eden that is my neighborhood. However, my mother considered the trimming of her tree to be “mutilation” of her personal property. My neighbor and my mother had different visions of what Eden means and these differences resulted in my neighbor crying after my mother expressed her disapproval in a few choice words. The differing opinions on the “Eden” that is my suburban neighborhood ended in a no more than a few tears and hurt feelings, but in other parts of the world the end result is not nearly this pleasant.

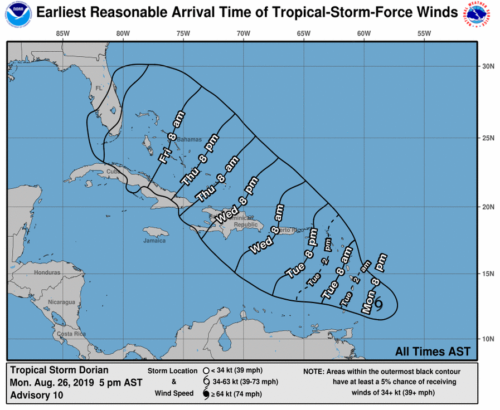

The theme of "nature as a virtual reality" was the most confusing take on how nature can be seen, but given the changes in technology that have occurred even in the past 20 years, it is hard not to see nature becoming a virtual reality as the way of the future. In fact, so much of what we know and understand about the physical world is based on models of things we cannot tangibly see. These models of natural events are, in fact, virtual reality. They are simplifications and simulations of complicated processes that, in a sense, just give us the best “guess” that science can provide given the data, tools, and knowledge we have at the time. These simulations are especially important now as extreme weather events and climate change are becoming more common-place. When I was an undergraduate student in Florida, we would see hurricane track projections all the time during hurricane season and these projections were enough to cause people to leave town, start bulk buying water, and board up their homes. These projections are shared over the course of days and change constantly, but they have tangible effects on the way Florida residents interact with the natural world.

Earlier this month Hurricane Dorian hit the Bahamas for more than 40 hours, and more than 50 people were killed as a result of this storm4. Hurricane Dorian was originally listed as a tropical storm on August 24th but did not become a hurricane until August 28th, eventually hitting the Bahama’s on September 1st5. During this time, the simulations and models of the hurricane made it possible to monitor the movement, wind speeds, and direction of the hurricane before it made landfall. Although this monitoring did not relieve the Bahamas of the devastation that occurred on Abaco Island and other Bahamian islands, there were models that accurately predicted the day and even the time that Hurricane Dorian would make landfall on the Bahamas. These simulations are an example of how the virtual “nature” can impact how countries around the world are able to predict and prepare for the impacts of real-world natural events.

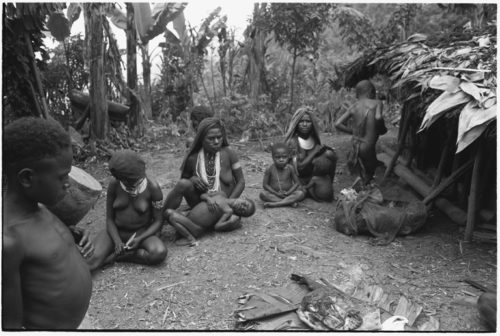

While Cronon spends much of his time discussing the many ways that we can view nature, Rappaport wants to look beyond culture to examine the lives of the Tsembaga people in New Guinea. Rappaport spent 14 months in New Guinea to objectively study the Tsembaga people as they relate to their ecosystem. One of the strongest links to the relationship the Tsembaga have with the surrounding ecosystem is the relationship that they have with the pigs they raise. The Tsembaga raise pigs so that they can be used as a source of protein and offered to their religious figures as a form of sacrifice. The pigs are useful to humans in this area because they keep residential areas free of trash and they can help with the tilling of soils in the gardens,. The humans are useful to the pigs because during times when the herd grows large, the humans end up feeding the pigs food that is suitable for human consumption. The relationship between the pigs and the humans is mutualistic until the herd grows too large to be managed by the women. When this happens, the pigs are slaughtered for a religious offering. The ecosystem where the Tsembaga live is cyclical in nature because their methods are repeated over and over throughout generations, just like many other natural systems.

During our class discussion we mentioned that although the Tsembaga and their interactions with the natural world show similarities between other natural cycles, this relationship is NOT self-sustaining. Natural cycles like the calcium carbonate buffering system in the world’s oceans can be modified by human inputs, but overall the ecosystem can self-regulate without human interaction and will persist without human contact. The ecosystem in which the Tsembaga live is not self-regulating or persistent in this same way. The pig populations would not be controlled on a cyclical cycle without the human interactions. So, although many people in the modernized Western world would consider the Tsembaga to be a “natural” part of their local environment and ecosystem, the Tsembaga have actually modified the ecosystem to suit their own needs. The work of Rappaport was revolutionary for its time, but we now know that it did not build a complete picture of humans as part of larger ecosystem, regardless of culture.

Biersack’s 1999 article “Introduction: From the ‘New Ecology’ to the New Ecologies” begins by summarizing and building on Rappaport's work. Biersack believes that the relationship between the nature and culture can be best explained by using three “new ecologies”. The first ecology is “symbolic ecology,” which uses ideas like magic, cosmology and fertility rituals to explain the natural world. In fact, one of my classmates mentioned that this reminded her of how myths such as werewolves were used to provide reasonable explanations for mental health disorders. The true biological cause of the changes in mood and personality were unknown, so leaning towards the supernatural provided ample explanation of what was happening in the natural world.

The second ecology that Biersack explains is the "historical ecology". The historical ecology essentially states that nature is a “contingent product, a sediment of human practice”6. I thought this concept was really interesting because what is nature without human interaction? For as long as humans have existed, we have been modifying the world around us to fit our needs, so is there any real “nature” that has been completely untouched by mankind in some way? I would argue that there is not, but also that this is not an inherently bad thing. No life on Earth is harm free. If a giraffe eats the leaves off a tree, the tree has now been modified or harmed by that giraffe. Humans, just like all other animals, modify and harm the environment but is the scale of which we are harming the environment that is troublesome. I think accepting the idea that there is no truly “natural” nature is interesting because when we look for nature, we often consider it to be a place where humans aren’t, but just because humans are not there now does not mean that humans have never been there before and have never modified the landscape into what we see today.

Biersack ends with the "political ecology". Political ecology acknowledges the role that imperialism, colonialism and capitalism have had on the ways that we view the natural world. The role of colonialism on culture and the way we view nature is one topic I wish we would have been able to spend more time discussing in lecture. I am genuinely interested to see how my classmates see the impacts of colonialism on modern society and on our opinions of nature.

References:

1. Britannica, T. E. of E. (2016, February 25). Kaleidoscope.

2. Cronon, William, ed. Uncommon ground: Rethinking the human place in nature. WW Norton & Company, 1996.

3. Laie, Benjamin. T. (2018, January 12). Garden of Eden.

4. Brulliard, K. (2019, September 14). Bahamas struggling for a way forward after Hurricane Dorian's devastation.

5. Frazin, Rachael., & Axelrod, Tal. (2019, September 7). Death and destruction: A timeline of Hurricane Dorian.

6. Biersack, Aletta. (1999). Introduction: From the “New Ecology” to the New Ecologies. American Anthropologist. 101. 5 - 18. 10.1525/aa.1999.101.1.5.

About the author

Faith Taylor

Faith Taylor is a second year master's student at the University of Maryland College Park. She is in the Marine, Estuarine and Environmental Sciences program and her concentration is in environment and society. She is advised by Dr. Michael Paolisso. Her thesis work focuses on using a comparative analysis to assess how environmental injustices are captured by case studies and screening tools. Her interests include race, environmental justice, environmental racism and vulnerability.

Next Post > Kicking off another semester of Environment and Society

Comments

-

Hamani Wilson 6 years ago

Very well stated article. I have been very enamored with the concept of political ecology. The connection to recent history and events also added to the strength of your blog post.

-

Taylor Gedeon 6 years ago

I love the kaleidoscope reference! Really neat way to visualize 'perspective' and what we each see.

-

Suzanne Spitzer 6 years ago

Great blog, Faith! I am also looking forward to talking more about political ecology and environmental justice in future weeks, especially since so many of us are interested in those topics. This week's introduction to concepts like culture and different ways of knowing nature will hopefully serve as a great launching pad for future discussion!

-

Maria Rodriguez 6 years ago

Good job Faith!! When I read Cronon's allusions to cultural visions of nature related to monotheistic religions I wondered how the vision of nature for other religions is. So, I asked an Indian friend about her vision of nature and she told me that her education was so influenced by British culture than her vision of nature is similar to the Christian vision. This seems an impact of colonialism to me...

-

Isabel Sullivan 6 years ago

I loved your blog! I especially like the idea of everyone's own Garden of Eden perception. I think realizing this difference of how people see the environment is crucial when we are looking at how people interact with the environment.

-

Andrea Miralles-Barboza 6 years ago

As a former long-time Florida resident I can attest to this phenomena of the public reacting really quickly to models they don't always completely understand. Actually, I do not fully understand how these projections are made even though my father has been doing modeling my entire life, but I do see the value in them.

Visual/virtual environment was the most puzzling topic to me out of all these readings so I'm glad I was not the only one perplexed.

Good job :)

-

Alison Thieme 6 years ago

Great blog post! I liked your example of conflicting views of nature as Eden, though I ponder the subtext of the phrase: "in other parts of the world the end result is not nearly this pleasant." Conflict resolution is both a global and local issue with varied results occurring everywhere. We might be able to use that phrase as a jumping off point for examining how colonialism impacts our views of societies and exploring the concept of ethnocentrism.

-

Michael J. Paolisso 6 years ago

Faith,

Very nice posting. I am glad you came around a little to seeing the concept of cultural lenses as useful. I appreciate your comparison of cultural lens to a kaleidoscope. What do you need the who kaleidoscope to understand what you see? I like your discussion of natural as virtual, digital, modeled, etc., all technology driven factors that physically distance us from experiences in the natural world, but are increasingly "standing in for nature." This is a little unsettling, but that is my cultural values speaking. Again, a very thoughtful blog. I didn't realize that you practice rebel behavior (just kidding).Michael

-

Megan Munkacsy 6 years ago

Love the werewolf shout out ;) This is a great balance of the technical topics we covered in class and your personality. The vegan pizza made me chuckle. Also really appreciate you making the point that a natural system having an interaction with a human does not make nature tainted. It just makes it part of the cycles of nature.

-

Amanda Rockler 6 years ago

Great linking in modern day events with the class discussion and readings. Imagery is really great but vegan pizza is something I still struggle with :-)

-

Enid 6 years ago

Great post! Love the kaleidoscope analogy! Wonderful explaining the different ecologies. I had trouble understanding them when I was reading, but you cleared all my questions.