Rupert and I Visit the Anthropocene

Bill Nuttle · 1 comments

My son, Rupert, and I decided to visit the National Gallery when he was home in Ottawa not long ago. A collection of photographs and videos called the Anthropocene has been drawing crowds all winter. An afternoon together at the art gallery seemed an ideal opportunity for some intergenerational bonding. As it turned out, if it weren’t for a virtual rhinoceros, I doubt that I could have survived with my parental dignity intact.

Rupert and I come at the

Anthropocene from different perspectives. The Anthropocene is proposed as a new

geologic era in which humans have emerged as a primary force altering the

planet. Rupert, an artist and writer, has written about this for the National

Gallery magazine, whereas the environmental impact of human activities has

been the focus of my entire career as an environmental engineer. But the most

important difference between our perspectives is generational.

The Anthropocene exhibit unfolds through a series of well-lit, high-ceilinged galleries. On entering, we encounter a video on a large screen showing a trip through the world’s longest tunnel, the Gotthard Base Tunnel, which runs for 35 miles beneath the Alps in Switzerland. Tunnels, along with road cuts and embankments, are one of the entirely new geomorphic forms that characterize the Anthropocene era. The video, shot from a camera mounted on the nose of a train, is mesmerizing. I feel myself being drawn headlong down a passage stretching to infinity. Slyly, the question is planted, “Is there a light at the end of the Anthropocene?”

The tunnel video evokes the memory of a half-forgotten future from my youth. The kaleidoscopic pattern caused by the onrush of signal lights emanating from the tunnel’s vanishing point recalls the Stargate sequence from Stanley Kubrick’s film, 2001: A Space Odyssey, one of the greatest movies ever made. With its release in 1968, at the height of the race to the Moon, my generation embraced a vision of humans transcending our earthly origins and venturing out into the limitless frontier of space. Space still beckons, but the future promised for the year 2001 is now behind us.

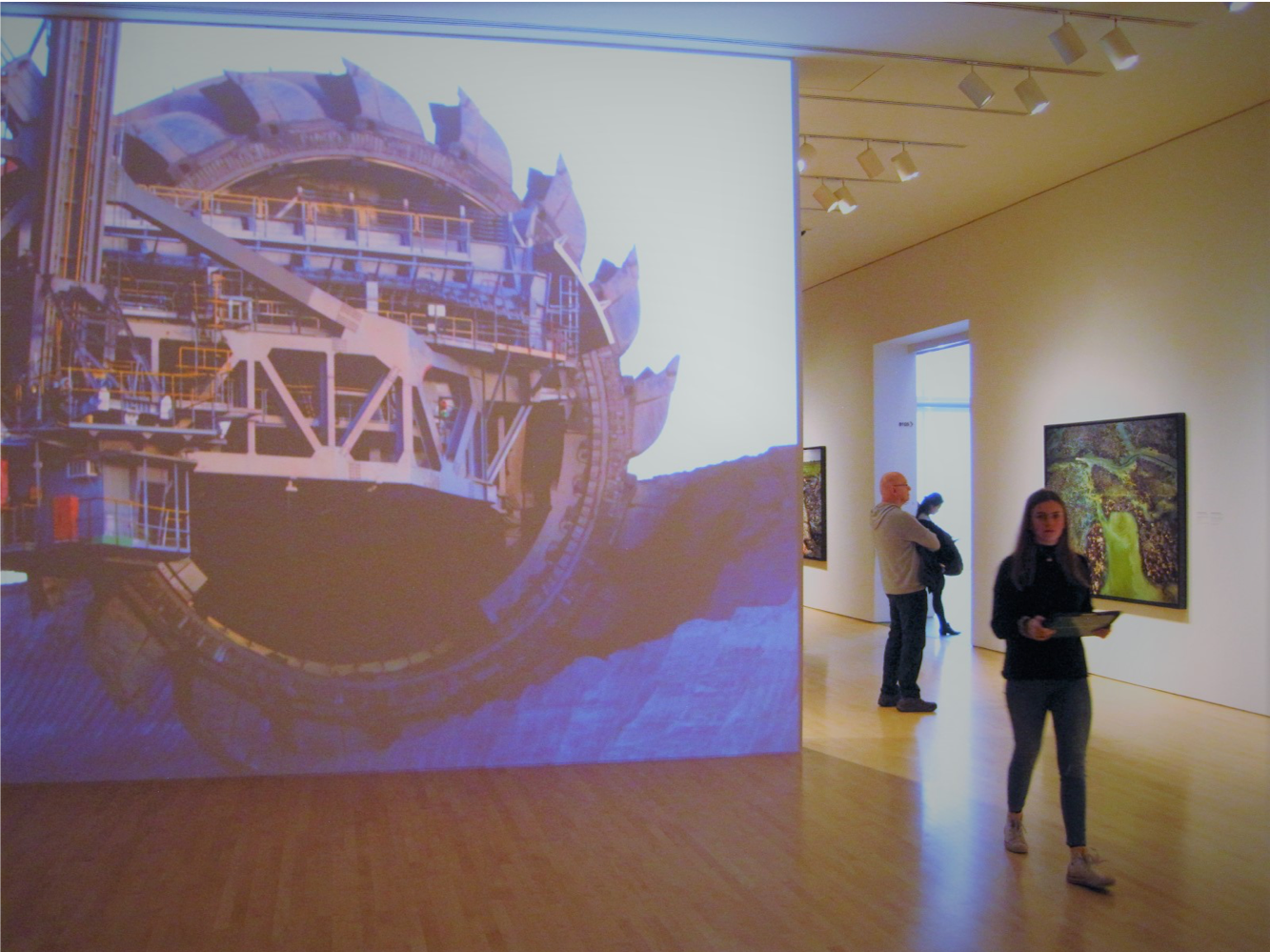

After the tunnel, there are more videos, some of them interactive, and more than two dozen large format, high-resolution digital images, mostly shot from above using drones. The artists seek to impress on us the daunting scale achieved by human activity in the 21st century. Huge machines sculpt the earth. Human habitations extend to the horizon in all directions. A trash dump, grown to the scale of a habitable landscape, is mined. All is artfully rendered. The photographer, Edward Burtynsky, has made a career creating images that mine owners are proud to hang on their walls.

A few images of wild nature are peppered

in among the industrialized landscapes - virgin forests, a coral reef. These

are rendered in the glorious style of the popular Planet Earth videos, or

National Geographic Magazine if you are of an older generation. As engaging as

these images are, the overall message is at once ambiguous and ominous. There

is no commentary, no interpretation, no authoritative explanation. There is

only the exhibit title, “Anthropocene,” which implies that we are witnessing a

profound transformation of the Earth.

But, not all humans are equally responsible.

These transformed landscapes have come into existence, for the most part, at

the hands of my generation. And, if things continue on their current

trajectory, the natural landscapes likely will be lost within Rupert’s lifetime.

Out of an impulse of paternal generosity, I had paid our admission into the

Anthropocene, but now I begin to doubt that this was such a good idea.

Finally, we enter the last gallery, one last chance to have it all explained, and a chance at redemption.

A few exhibit-goers stand around with their phones out. The room appears to be empty, until Rupert hands me an iPad from a rack on the wall. Holding the iPad just so, Rupert shows me that, in fact, the room contains two virtual installations—an eight-foot high pile of elephant tusks and, improbably, the world’s last male northern white rhinoceros. The elephant tusks complement the video we have just seen about illegal ivory seized in Kenya. The pile, only a small part of the huge cache that was burned in the video, provides a measure of the enormity of the destruction of elephant herds from poaching. The rhinoceros is also now dead, the species extinct.

These virtual installations are the pièce de résistance of the Anthropocene exhibit. The artists have created each by stitching together thousands of digital images. An app running on the iPads and downloadable onto cell phones allows us to view the installations from every angle as we move about the room. Mercifully, the intrusion of technological wizardry is a distraction. My sense of guilty culpability is relieved. Exasperation at my clumsiness with the iPad dissipates any intergenerational resentment that Rupert might have been harboring.

I am not sure, but I think I see the rhinoceros wink.

The distractions of technology aside, it is easy for my generation to be unmoved by the transformation that we are witnessing. Our future is behind us. But, our reluctance to alter the status quo is the inertia that propels the world forward into the Anthropocene. Inaction is less of an option for Rupert and his generation. Their future still confronts them.

There is, I think, hope. Late last

year, scientists of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change issued a report that, uncharacteristically, has

become something of a best-seller. In it, they challenge humanity to transcend

our dependence on fossil fuels and venture toward the goal of building an

equitable, sustainable world. If Stanley Kubrick had written it, the title

might have been 2030: A Climate Odyssey.

This is a vision of the future that Rupert’s generation might embrace and

perhaps, in time, remember.

Next Post > Finding the value of Transdisciplinary Research on Food Security and Land Use Change

Comments

-

Cinny Beggs 7 years ago

When I started reading this, I knew that "anthropocene" was foreign to me. Upon completion of the report, I feel guilt for my lack of action to halt the harm to the earth. I have my empathies, but not my capabilities. You should be thankful that your field of study and career has not only kept you in the forefront of prevention, but can teach the affected generation of the importance of "saving the planet" for all living things.