Science can inform policy, but it may take advocates to drive changes

Yuanchao Zhan, A.K. Leight, Kristen Lycett · | Applying Science | 1 commentsHave you ever heard about Bill McKibbens and his three numbers? If not, you might want to read about it, if you are concerned about the future of the earth. In his Rolling Stone article, Global Warming’s Terrifying New Math, McKibben used three simple numbers to explain the serious climate change situation we face right now, and we will face going forward [1].

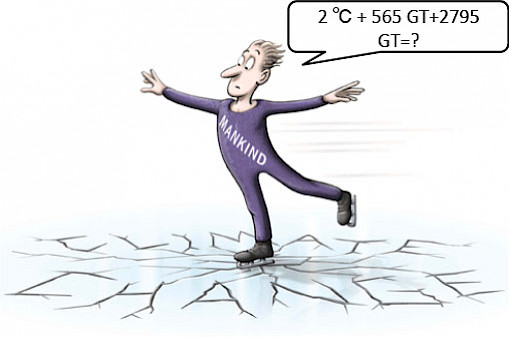

The first number, 2° Celsius, is the safe number that scientists think increasing global temperature should be below. However, a 0.8 degrees Celsius increase on the average temperature of the planet has caused far more damages than most scientists expected. 565 gigatons, the second number, is the maximum amount of carbon dioxide humans can pour into the atmosphere by mid-century in order to achieve the goal of controlling the temperature. While even if we stopped emitting carbon dioxide right now, the temperature would still rise another 0.8 degrees. Moreover, CO2 emissions all around world are continuously increasing. Thirdly, 2,795 gigatons describes how much carbon is ready to be sold by fossil-fuel companies and countries. The terrible thing is this number, 2,795 is five times higher than the so-called safe number 565.

By pointing out the meaning of these three numbers, Bill McKibben faced the public with apparent honesty, and used an alarmist tone to tell about the dangers associated with not taking global warming seriously [2]. Also, as a knowledgeable journalist he used a mental model and took the audience on a journey from the science and the facts to advocacy and made a difference with climate change [3]. Similarly with Bill McKibben, these advocacies deep analyze, synthesize the relative paper and piece together a bigger whole explanation of the problems we face. And finally, they used the languages most people can understand, get people to care about these issues and influence the policies, just like Rachel Carson and her book Silent Spring. Her book called attention to the danger of chemical industrials and the use of pesticides, and successfully appealled people to stop the use of DDT as a pesticide, ultimately saving the osprey and bald eagle populations in the US [4].

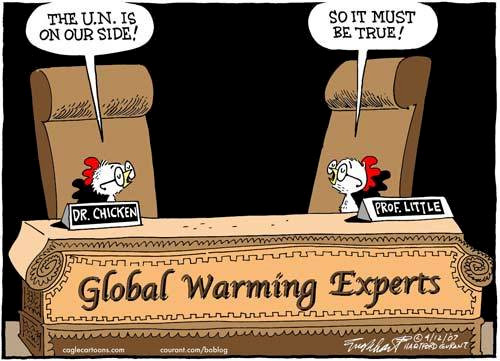

The problem with advocates is sometimes they overreact with the environmental conditions we are facing. They do not pay a lot of attention to the scientific details, choosing instead to lead with advocacy and some personal opinions, and display like the Chicken Little. These personal ideas cause an unnecessary community panic and scare community into a rush for government action.

However, scientists as experts in environmental science also face a dilemma, how to mobilize people with science? Environmental scientists may find themselves in an awkward situation when communicating controversial findings. The may feel they have to stand up and publically announce their view on issues based on their science. However, sometime their advocacy ruins scientific credibility, and they may have a harder time publishing papers because some of their colleagues think that they overstepped their knowledge base.

As an expert in the field, how can you support science and subsequent management, without putting your own opinions out there? The bottom line here is you should follow the ethical standards, Hippocratic Oath for scientists [5]. Your conclusions and recommendations should be based on solid data and reasonable predications. Scientists should never exaggerate the facts. In addition, by leading people to a management conclusion, you need to be available to answer the question “What happens next?” Thus, we can start advocacy with science and then use that as a jumping off point for discussion in how best to change management and policy. The other possible way is to hand off the facts, find somebody you trust and let that person advocate your common views.

Climate change and other environments problems might not all be doom and gloom, but we still need to take it seriously. Scientists and journalists both play important roles, and have their individual responsibilities. By solid investigation and reasonable modeling scientists can estimate current environmental dynamics and predict future conditions more precisely, and can also provide feasible recommendations. In contrast, journalists can take advantage of their detachment from science and call on the public to care more about climate change, and thus help to fill the gap between knowledge of this issue and subsequent action. Just like Bill Nuttle, who is an Environmental Consultant for Environmental Science, Hydrology, and Water Resources, said “climate change is not getting addressed only by blogging or any other personal behaviours. It has to be translated to political action.”

References

1. McKibben, B. “Global Warming’s Terrifying New Math.” Rolling Stone Politics. July, 19, 2012.

2. Mark, J. “Bill McKibben’s Rolling Stone Article was a Hit - So Why didn’t It Make a Splash.” Earth Island Journal. September, 17, 2012.

3. Nisbet, M. C. “Nature’s Prophet: Bill McKibben as Journalist, Public Intellectual and Activist.” Joan Shorenstein Center on the Press, Politics and Public Policy Discussion Paper Series. March, 2013.

4. McLaughlin, D. "Fooling with Nature: Silent Spring Revisited". Frontline. PBS. 24, August, 2010.

5. Cressy, D. “Hippocratic Oath for Scientists.” Nature news blog. September, 12, 2007

Authors

Yuanchao Zhan, A.K. Leightand, and Kristen Lycett

Next Post > Teaching with a ‘flipped classroom’ over an interactive video network

Comments

-

Melissa 13 years ago

Really excellent summary of our class readings and discussion. The cartoons really hit the points home. Well said!