The Power in Soft Power: The Chesapeake Bay Commission

Vanessa Mukendi · 6 commentsIf you grew up in the Chesapeake Bay watershed like me, when you hear the words Chesapeake Bay, you may think of summertime on beaches like Ocean City, eating crabs with friends and family, or recreational activities like kayaking. You may also think of important species of the bay like oysters or blue crabs and of wetlands and aquatic vegetation such as eelgrass. From recreation to ecosystem biodiversity to water quality, the Chesapeake Bay plays a key role in many lives. The Chesapeake Bay watershed encompasses Maryland, Virgina, Washington D.C., Delaware, Pennsylvania, West Virgina, and New York. There are many important protectors of the Chesapeake Bay, and the Chesapeake Bay Commission has a unique role.

What is the Chesapeake Bay Commission?

The Chesapeake Bay Commission was created in the early 1980s by three key states that are part of the Bay: Maryland, Virginia, and Pennsylvania (“History,” n.d.) Although formed in the early 1980s, the commission’s formation traces back to a 1978 joint study composed of the Maryland-Virgina Chesapeake Legislative Advisory Commission (“History,” n.d.).

A bi-state commission was then in favor at the time, due to no federal statutory limitations, focusing on the bay restoration through state responsibility and bridged policy between the states. The Chesapeake Bay Commission also guided attention to Bay issues identified by the states' executive agencies by offering policy guidance to state legislatures (“History,” n.d.). Pennsylvania then joined the commission in 1985 (Maryland State Archives, n.d.).

The key purpose of the development of the Commission was to have a more collective legislative management of the Chesapeake Bay. Currently, the commission consists of 3 official member states: Maryland, Virgina, and Pennsylvania. The Commission serves as a protector of the Chesapeake Bay by being a coordinator for state legislators, federal agencies, and other organizations (“History,” n.d.). The Commission also promotes collaborative resource planning and action among the executive agencies of its three member states and acts as a liaison to the U.S. Congress when it comes to matters of the Bay (Maryland State Archives, n.d.). The General Assemblies in each member state specified five specific goals that continue to guide the Commission today (Chesapeake Bay Commission, n.d. mission)

- to assist the legislatures in evaluating and responding to mutual Bay concerns;

- to promote intergovernmental cooperation and coordination for resource planning;

- to promote uniformity of legislation where appropriate;

- to enhance the functions and powers of existing offices and agencies; and

- to recommend improvements in the management of Bay resources.

Who is the Chesapeake Bay Commission?

With 7 members from each signatory state (Maryland, Virgina, and Pennsylvania) there are a total of 21 members that serve on the commission. Five members from each state are state legislators, and their terms coincide with their respective office (Maryland State Archives, n.d.).

Key achievements:

Since its formation, the Chesapeake Bay Commission has had significant achievements that help restore and maintain the health of Chesapeake Bay. This recently includes the commission’s pivotal role in the 2024 decision to update the Chesapeake Watershed Agreement.

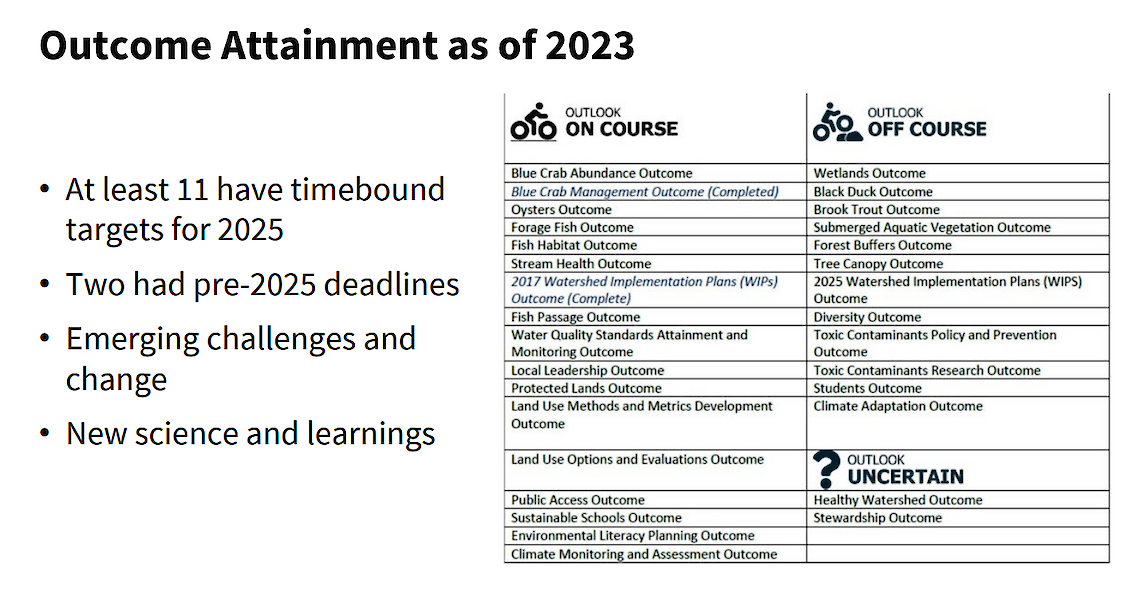

The previous agreement focused on 31 outcomes, where 2025 was the target date. The 2022 annual executive council meeting focused on that target date and tasked the principal’s staff committee to review the progress of the 10 goals and 31 outcomes (Chesapeake Bay Program, 2024). The development of “A Critical Path Forward for the Chesapeake Bay Program Beyond 2025” report aimed to revise and strengthen partnerships, conservation, and science of the Chesapeake Bay (Chesapeake Bay Program, 2024). The commission continues to play a key role in being a coordinator and legislative voice through state level action and policy and bringing diverse Chesapeake Bay Program partnerships together. For example, in May 2024, the Executive Director of the Chesapeake Bay Commission, Anna Killius, presented at Frostburg, MD on key reasons as well as broken down phases and possible courses of action on updating the Chesapeake Watershed Agreement involving a variety of partnerships for the Bay program beyond 2025 through the commission’s guidance (Killius, 2024). Figure 1 outlines outcome attainments as of 2023.

Now and future

The proposed guidance by the Chesapeake Bay Commission calls for an update of the 2014 watershed agreement focused on principles, goals, preamble, and management strategies with a focus on reaffirming continued collaboration and partnership commitments by the 2025 Executive Council meeting (Killius). By the 2026 Executive Council meeting, the current recommendations are to reaffirm, refine, and refresh outcomes and commit to the renewed partnership (Killius, 2024).

The Chesapeake Bay Commission has been and continues to be an advocate and bridge to partnerships for the Chesapeake Bay Program. The commission conveys information but does not have the legal power to dictate choices. This unique position of influence demonstrates the influence of soft power where collaboration, scientific information, and legislation can create pivotal outcomes for the health of Chesapeake Bay.

References

- Chesapeake Bay Commission. (n.d.). History. Retrieved March 31, 2025, from https://www.chesbay.us/historyMaryland State Archives. (n.d.). Chesapeake Bay Commission.

- Chesapeake Bay Commission. (n.d.). Mission. Retrieved March 31, 2025, from https://www.chesbay.us/mission

- Chesapeake Bay Program. (2024, March 29). Chesapeake Executive Council announces plans to revise existing watershed agreement. Retrieved March 31, 2025, from https://www.chesapeakebay.net/news/pressrelease/chesapeake-executive-council-announces-plans-to-revise-existing-watershed-agreement

- Maryland Manual On-Line. Retrieved March 31, 2025, from https://msa.maryland.gov/msa/mdmanual/38inters/html/04chesbf.html

- Killius, A. (2024). A path forward for the Bay Program. Chesapeake Bay Commission. Retrieved March 31, 2025, from https://www.chesbay.us/library/public/documents/Meetings/May-2024/6-Beyond-2025-May-24_AMK.pdf

About the author

Vanessa Mukendi

Vanessa is a current first-year graduate student pursuing her master’s in Environmental Management in Sustainability at Frostburg State University. Vanessa also earned her Bachelor of Science in Earth Science: Concentration Environmental Science at Frostburg State University with minors in Sustainability and Sociology. Before starting graduate school, Vanessa worked as a Conservation Research Program Manager at Bat Conservation International. Vanessa has a strong passion for environmental justice and community engagement and plans on continuing to implement that in her career.

Next Post > Climbing Down the Ivory Tower

Comments

-

Lina Goetz 10 months ago

Great job Vanessa, I like the layout of your post, the information flowed very nicely and was very interesting!

-

Sabine Malik 10 months ago

This is a super informative summary of the Chesapeake Bay Commission! The number of states that must agree to effectively manage the Chesapeake Bay Watershed is one of the major challenges with this system, so it's very important that we have bipartisan support facilitated by groups like the Chesapeake Bay Commission. I'm sure most people don't know that such a thing exists, but it is crucial for protecting the Bay's resources!

-

George Anim Addo 10 months ago

This is a well-researched and clearly presented article that effectively communicates the role and significance of the Chesapeake Bay Commission. The analysis of the Commission's "soft power" is a particularly insightful conclusion.

-

Zhongshi He 10 months ago

I really love how you look at how the Commission got started and how it's changed over time. It's so clear how it's different from a regulatory group because it's more about getting people to work together and making sure laws are made in a steady way. And I really liked the part about how it connects state legislatures with executive agencies and federal partners. That was really informative, especially in the context of the 2025 updates to the Watershed Agreement.

-

M.J. Parsons 10 months ago

Great job detailing the specifics of this organization. I also really like the graphic you chose to illustrate progress. It is easy to identify where the successes and opportunities are. Nice work!

-

Wyatt Palenchar 9 months ago

I think you did really well examining the Chesapeake Bay Commission and their importance. I also liked the infographic you included to demonstrate what work they are doing and what they are on track to complete.