Uniting Science and Community: Reflections from the 2024 Chesapeake Community Research Symposium

Taylor Ouellette · | Applying Science |“If we accept that we should seek not to save the Bay from people but for people, we will create a movement and watershed that works for everyone—for us and for nature.” - Hilary Harp Falk, President and CEO, Chesapeake Bay Foundation

Sunset from Spa Creek Drawbridge: Photo by Taylor Ouellette showing a quiet evening in Annapolis, MD, with boats on the water, taken on June 8, 2024.

Collaborative Efforts to Sustain the Bay

From June 10 to 12, I joined a diverse group of scientists, academics, researchers, GIS experts, and community members at the 2024 Chesapeake Community Research Symposium in Annapolis, MD. Together, we shared a goal: to deepen our understanding and enhance the protection of the Chesapeake Bay Watershed. The symposium highlighted remarkable collaborative efforts, such as the U.S. Geological Survey's use of advanced GIS and remote sensing to assess land cover and land use changes, alongside the Smithsonian Environmental Research Center's integration of participatory science with remote sensing to evaluate water quality. It was inspiring to see the extensive work being done to foster a more sustainable, healthy, and vibrant Chesapeake Bay Watershed. These initiatives are important as we navigate the challenges of a changing climate and its impacts on water quality management.

Fostering Diverse and Inclusive Decision-Making

The symposium emphasized a shift toward including those most affected by environmental changes in both research and decision-making. A highlight for me was hearing from Dr. Ashley Spivey, a member of the Pamunkey Indian Tribe and Executive Director at Kenah Consulting.

She highlighted the need for reciprocal relationships in conservation efforts involving Indigenous communities (8). Her powerful assertion, “Tribes are sovereign nations, not stakeholders,” urged us to rethink our engagement strategies (8). Spivey criticized the traditional top-down “practice of extraction” approach to leveraging Indigenous knowledge. She advocated for methodologies that prioritize tangible benefits for Indigenous peoples and actively involve them in determining how they wish to engage and benefit from such initiatives (8).

Addressing Nonpoint Source Pollution

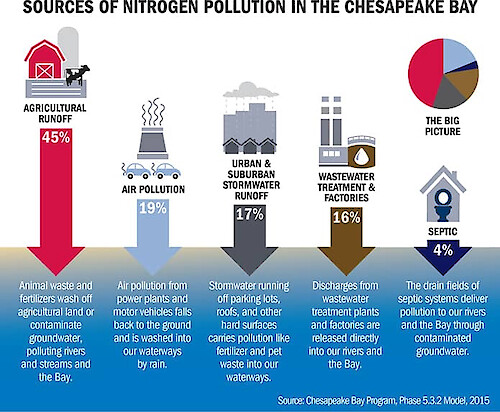

A central concern expressed at the symposium was nonpoint source pollution. This type of pollution comes from many sources, as opposed to a single identifiable one. The symposium discussed how nonpoint source pollution originates from various sources including fertilizers, wastewater, septic tank discharges, air pollution, and runoff from agricultural activities and urban areas. Dr. Allison Reilly of the University of Maryland addressed how septic systems contribute to water contamination in the Chesapeake Bay Watershed. The negative impacts of this pollution is increased by climate change-caused factors like inundation, increased flooding, and rising sea levels (4).

Nonpoint source pollution releases surplus nitrogen and phosphorus into the bay, leading to nutrient overloads that cause algal blooms. These blooms degrade water quality and can create dead zones—areas so depleted of oxygen that aquatic life cannot survive (4). The symposium stressed the need for effective solutions, such as Best Management Practices (BMPs) including cover crops and riparian buffers (7). Cover crops, like rye and clover, are planted during off-seasons to reduce erosion, improve soil health, and decrease nitrogen leaching into groundwater (9). Riparian buffers, which include plants like trees and shrubs, are planted along waterways to prevent nutrient and sediment runoff (9). These nature-based solutions absorb unused nutrients, minimize runoff, and improve water quality.

Martha Shimkin and Anna Killius noted that wetlands and riparian forest buffers, critical in mitigating nonpoint source pollution from runoff, are underperforming in restoration and conservation efforts (6). They pointed out that these efforts are not on track to meet the Chesapeake Clean Water Blueprint 2025 goals (6). This points to the urgent need for increased attention and action to preserve these vital ecosystems. Implementing such measures is key for the recovery and long-term ecological health of the Chesapeake Bay Watershed.

![Graphical illustration depicting various conservation practices aimed at reducing nutrient and sediment pollution within the Chesapeake Bay Watershed. The practices include buffer zones, controlled drainage, and reforestation among others, illustrated with symbols and arrows indicating their application across a stylized map.]](/site/assets/files/31496/usgs_ian_bmps.700x0-is.png)

This illustration from a UMCES-IAN fact sheet visualizes conservation practices that farmers can use to improve water quality in the Chesapeake Bay Watershed, based on recent USGS scientific insights. Image credit: Created by Lili Badri, Vanessa Vargas-Nguyen, and Bill Dennison. Fact sheet dated December 19, 2023.

Legislative Needs and Private Sector Engagement

Land cover and land use changes, particularly the conversion of natural habitats into large-scale industrial agriculture and livestock farming operations, have resulted in significant ecological consequences. These include biodiversity and habitat loss, which exacerbate pollution and runoff from industrial agricultural practices. Hilary Falk, President and CEO of the Chesapeake Bay Foundation, advocated for a "21st-century Clean Water Act" to meet the modern challenges of managing water quality in the Chesapeake Bay Watershed (2). Falk emphasized the need for stricter regulations on agricultural pollution and the potential for leveraging private industry to complement governmental efforts. She stressed the importance of ensuring the Chesapeake Bay Watershed remains a priority in national water quality initiatives (2).

Engaging with the Agricultural Community

The symposium also highlighted the essential role of the agricultural community as allies in combating nonpoint source pollution. Understanding and modifying the incentives for farmers is key to mitigating environmental impacts. This aligns with Dr. Michele Romolini and Dr. Keota Silaphone's discussions on adopting practices like wastewater use and planting cover crops. These practices are beneficial but also introduce unique challenges, particularly in terms of cost and implementation (5).

The Coastal Ocean Assessment for Sustainability and Transformation (COAST) Card project employs targeted listening sessions with the agricultural community to understand barriers and opportunities for improving agricultural sustainability in the Chesapeake Bay Watershed. The COAST Card is a stakeholder-driven tool that simplifies complex scientific data into clear, accessible report cards. These report cards communicate the watershed's health using social, economic, and ecological indicators tailored to community needs and priorities.

The listening sessions follow a station-based format with interactive activities. Participants are asked what they value in the watershed, what they see as threats, where they work, live, and play, and what indicators they want in future report cards. They also share their visions for a sustainable watershed and the necessary actions to achieve it. This approach helps identify barriers to sustainable farming practices and incentives that align with farmers' values.

Conclusion: A Collaborative Path Forward

The symposium was not just a forum for research but a convergence of individuals committed to creating practical and inclusive solutions for the Chesapeake Bay Watershed. This event was a powerful reminder of the importance of collective action and integrating science with community insights to foster healthy ecosystems and communities. As we continue with the COAST Card project, the guiding principles of inclusivity, respect for all stakeholders, and community-led science and decision-making will be crucial in achieving a sustainable future for the Chesapeake Bay Watershed.

Global Sustainability Scholars and Fellows (from left to right) Bailee Porter, Taylor Ouellette, and Kameryn Overton at the Chesapeake Community Research Symposium, June 10, 2024.

References

-

Chesapeake Bay Foundation. (n.d.). What is killing the bay? Retrieved June 14, 2024, from https://www.cbf.org/how-we-save-the-bay/chesapeake-clean-water-blueprint/what-is-killing-the-bay.html#continued

-

Falk, H. H. (2024). Chesapeake Bay restoration: Managing water quality for living resources in a changing climate. Plenary presentation at the 2024 Chesapeake Community Research Symposium, hosted by Chesapeake Community Modeling Program, Annapolis, MD.

-

Reilly, A., Tasnim, J., Kjellerup, B., et al. (2024). Septic to sewer? Justice-focused strategies for addressing coastal septic failures under sea-level rise and increased flooding. Presented at the 2024 Chesapeake Community Research Symposium, hosted by Chesapeake Community Modeling Program, Annapolis, MD.

-

Remmers, V. (2024). Chesapeake Bay dead zone predicted to be slightly larger than average. Chesapeake Bay Foundation. Retrieved June 14, 2024, from https://www.cbf.org/news-media/newsroom/2024/all/chesapeake-bay-dead-zone-predicted-to-be-slightly-larger-than-average.html

-

Romolini, M., Siglar, A., Leisnham, P. T., et al. (2024). Agricultural water management in a changing Mid-Atlantic: Stakeholder experiences and attitudes towards alternative water sources, weather variability, and related factors. Presented at the 2024 Chesapeake Community Research Symposium, hosted by Chesapeake Community Modeling Program, Annapolis, MD.

-

Shimkin, M., & Killius, A. (2024). Beyond 2025. Plenary presentation at the 2024 Chesapeake Community Research Symposium, hosted by Chesapeake Community Modeling Program, Annapolis, MD.

-

Silaphone, K. (2024). An assessment of cover crop nitrogen efficiencies in the United States Coastal Plain Province, 1980 - 2022. Presented at the 2024 Chesapeake Community Research Symposium, hosted by Chesapeake Community Modeling Program, Annapolis, MD.

-

Spivey, A. (2024). Chesapeake Bay restoration: Managing water quality for living resources in a changing climate. Plenary presentation at the 2024 Chesapeake Community Research Symposium, hosted by Chesapeake Community Modeling Program, Annapolis, MD.

-

Webber, J. S., Clune, J. W., Soroka, A. M., Hyer, K. E., Badri, L., Vargas-Nguyen, V., & Dennison, B. (2023). Your land, your water: Using research to guide conservation practices on local farms in the Chesapeake Bay watershed. University of Maryland Center for Environmental Science. Retrieved June 14, 2024, from https://ian.umces.edu/publications/your-land-your-water-using-research-to-guide-conservation-practices-on-local-farms-in-the-chesapeake-bay-watershed/

About the author

Taylor Ouellette

Taylor Ouellette, a Global Sustainability Scholar Fellow, is engaged with the Coastal Assessment for Sustainability and Transformation (COAST) Card project at UMCES-IAN this summer, an international and transdisciplinary initiative. She is currently pursuing her Master of Ecology in the Environment, Ecology, and Energy Program at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill. As a member of the Human Ecology Lab, her research primarily explores the political ecology of conservation. She focuses on resource conflicts and the potential of participatory environmental governance.