Visiting the Great Lakes to talk report cards and communication ideas

Jason Howard · 2 commentsThe Great Lakes are a naturally interconnected group of basins that hold 90% of freshwater in North America. Keeping that water healthy is key to having waters for swimming, beaches for relaxing, and scenic vistas for the surrounding communities. Healthy fish stocks attract tourists to the area and support First Nations communities. More importantly, the lakes are still the source of drinking water to over 40 million people in the surrounding communities, including Toronto, Chicago, and Cleveland. Despite their social, cultural and economic importance, the Great Lakes face serious threats from invasive species, toxins, water diversion, wetland destruction, sewage overflows, and climate change. People are making efforts to solve these environmental problems, and organizations are working to improve how efforts and issues can be communicated to have greater impact.

Heath, Emily and I visited Ontario on May 15th-17th to meet with the Lake Simcoe Region Conservation Authority and other groups to discuss different ways to present their environmental restoration work. This trip also marked my first IAN workshop and first international trip with IAN. On the first day of our trip, we traveled to the Lake Simcoe Region Conservation Authority in Newmarket, Ontario to talk to Ben Longstaff, Carolyn Switzer, and Michelle Palmer about the incredible strides in environmental monitoring and management for Lake Simcoe: a smaller lake sandwiched between the Huron and Ontario lakes. The Lake Simcoe Protection Act passed in 2008 as Canada’s first lake-specific legislation. This act was followed by the Lake Simcoe Protection Plan in 2009 to address long term environmental issues in the watershed.

The Protection Plan will have been active for ten years next year, and the major landmark warrants something big to celebrate. Ben Longstaff is now the Integrated Watershed Management general manager of Lake Simcoe Region Conservation Authority, but previously worked at IAN and contributed to the very first Chesapeake Bay report card. He knows IAN’s style, and invited us up to discuss ways to celebrate the Protection Plan’s milestone. It’s too early to mention what could be in the works, but a book sure would be an appropriate way to reflect on years of projects, collaborations, and achievements.

The following two days were spent teaching Ontario’s Ministry of Environment and Climate Change (MOECC) and their partners IAN’s ecohealth report card making process. The providential government of Ontario has a formal strategy to address issues in the Great Lakes Basin. They share resources, coordinate management efforts and scientific activity, and then regularly review their progress and action plans. The MOECC still seeks new ways to engage stakeholders and evaluate Ontario’s role in overall basin management and adaptation. We shared IAN’s report card development process with hopes that they can use our techniques to further assess lake health and their involvement.

For the workshop's first activity we played the board game Get the Grade! that was developed with WWF and the Engagement Lab at Emerson College. In this game, players are assigned roles as ecosystem stakeholders such as farmers, sanitation officers, and beverage consultants. In these roles, they take turns making decisions that affect the ecosystem (Figure 1). It was a fun icebreaker and a great way to recognize how cross sector communication can benefit overall ecosystem health.

After that, we started with the first phase of our report card process: Planning. Here we discussed the intended audience of a report card, the stakeholders involved, and the context required to create a meaningful product. We were talking to a group that regularly releases environmental reports and plans workshops, so folks jumped right into the nuances of stakeholder influence and interest. It was a pleasure to hear discussions about how to best include the basin’s indigenous groups, and how their perception of environmental resources might require a different style of communication. This was a group of experienced professionals, but still very open to learn our perspectives and ideas regarding the reporting process.

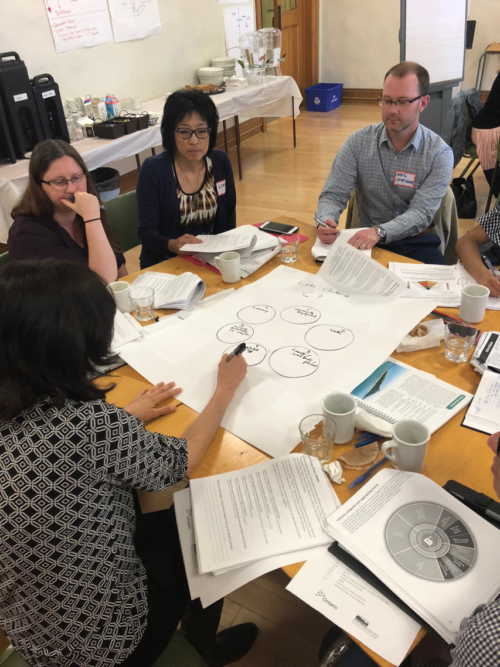

For the rest of the day we opened our report card toolbox, sharing our five step development process along with activities and tips to facilitate advancement. Throughout this whole process we considered the Great Lakes basin as an example. We talked about how to conceptualize the Lakes, and introduced SNAP! as a means determine their most important values and issues (Figure 2). We talked about how to choose indicators of health that would best reflect those characteristics deemed important in SNAP! Not only were there over fifty participants (Figure 4) but they asked interesting questions and gave insightful comments. We ran out of time, though fortunately conversations continued at a happy hour down the street. In a social atmosphere with brews in hand, folks seemed uninhibited in expressing their passion for environmental management, and to my surprise, also seemed to enjoy working for the governmental of Ontario. They also seemed really keen on civil service. The sense of duty to community expressed by participants is one I respect and share.

On Day two of the workshop, Heath discussed how to define threshold indicators. For my IAN workshop debut, I discussed scoring procedures and report card grades. Emily followed up with a lesson on science communication and document design. At this point, it was early afternoon of the last day of the workshop. This workshop had been an active process involving difficult topics, physical movement, drawing, presenting, and detailed discussions. At this point people were getting tired, but Heath maintained interest by explicitly addressing concerns and questions posed by participants, and wrapped things up with a short discussion on to improving an ecosystem’s status. Participants recognized the power that predictive models and certain messages have in creating change, citing “Tipping Points,” a document about the Great Lakes, as a major impetus for the investment of billions of dollars for lake management. We finished the workshop optimistically, but with awareness of impediments that could develop after the upcoming provincial election.

From the workshop we drove straight to the airport to get back to Maryland. The trip was perfectly timed to witness Toronto’s beautiful spring time, but we’ll have to return to explore the city. It wasn’t until the flight back that I got to see the Great Lakes that we had talked so much about (Figure 5).

Next Post > How to improve interdisciplinary collaborations: lessons learned from scientists studying team science

Comments

-

Reginald 7 years ago

I was wondering if you ever considered changing the layout of your site?

Its very well written; I love what youve got to

say. But maybe you could a little more in the way of

content so people could connect with it better. Youve got an awful lot

of text for only having one or 2 pictures. Maybe you

could space it out better? -

Max Hermanson 7 years ago

Thanks for your input. We are actually in the process of redoing our website, so stay tuned.