What’s nature got to do with it?

Alana Todd-Rodriguez · 10 commentsWhat's nature but a second-hand construction?

By: Alana Todd-Rodriguez

Walk outside the nearest door and look around. What do you see? Does your front lawn, campus grounds, or nearby cityscape count as a place of nature? Your answer to this question is a product of your upbringing and cultural influences. The Oxford Dictionary defines nature as: "The phenomena of the physical world collectively, including plants, animals, the landscape, and other features and products of the earth, as opposed to humans or human creations1." This definition reflects a growing sentiment that the human species can defy the laws of the universe to exist outside of the natural world. In reality, humans' ability to adapt to nature has ensured our species' survival over millennia, and our connection (or perceived lack thereof) to the environment is a product of cultural constructions from our ancestors and beyond. Just as love played no role in Tina Turner's relationship, the natural world might not be as related to the concept of "nature" as one might think.

Last week, our MEES 620 class discussion opened with a critical look at Irvine, California. Irvine is an example of how humans have imposed their cultural ideals onto a landscape and transformed the natural ecosystems into their very own meticulous version of Eden. Irvine's marketing website describes the city as a place where business and nature were built to coexist in harmony, perfect for those seeking to "get outside and experience nature" through manicured parks and year-round scenic vistas.

Cities such as Irvine are not a unique phenomenon in the United States. As Dr. Paolisso described the intricate planning of Irvine, I couldn't help but think of my own hometown, St. Petersburg, Florida. Following the advent of central air conditioning and the installation of a railroad line, people rushed south in droves to enjoy a piece of their very own subtropical paradise. From 1920 to 1990, Florida's population increased by 1,300 percent as numerous families, mine included, claimed waterfront property throughout the Sunshine State2. What was once vast tracts of mangroves and other tidal marshes are now multi-million-dollar homes that lie at or below sea level. This artificial Eden came at the cost of draining and paving over much of the state's biodiverse coastal ecosystems, which also function as buffers to storms and flooding. When large hurricanes threaten Florida, like Irma, we are sitting ducks- vulnerable and forced to accept the blame for our own demise. Is it worth it? Well, I don't think so, and that is why I chose to go to school in Maryland.

Nevertheless, something very compelling must drive over 600 million people to value beauty over safety and live in low elevation areas near the coast3. This week's articles by Steward, Rappaport, Cronon, and Ellis argue that culture is the culprit.

Our class discussion proceeded to trace the earliest studies of culture, which eventually evolved into the fields of Anthropology, and later Environmental Anthropology. Early "armchair anthropologists," such as Lewis Henry Morgan, paved the way for subsequent anthropologists, like Franz Boas and Roy Rappaport, to understand the value of participant observation and immersive field work. Culture was eventually accepted as something that is learned and shared, including knowledge, values, and traditions, which depends on historical and environmental contexts.

Julian Steward used a systemic approach to study culture and the environment with the Great Basin Shoshonean communities4. He was interested in the ways in which the environment, through natural resource availability, shaped their cultural core. The arid conditions of the Great Basin provided a backdrop of unpredictable food sources that required complex, transient exploitative techniques. Steward's ethnography details the unique cultural-ecological adaptations that the Shoshone groups integrated on the familial level. One student questioned whether the Shoshone would have adapted to the indirect forces of the modern-day Anthropocene era, to which Dr. Paolisso suggested that they might have maintained some of their most central cultural practices, like the northern salmon feasts, but within modern settings.

![Tsembaga hand out salted pork fat to their allies, redistributing their environmental resources in efforts to forge key alliances. ([Pig festival, pig sacrifice, Tsembaga: behind ritual fence, decorated Tsembaga men wait to distribute salted pork fat to allies, November 1963]. Roy Rappaport Papers. MSS 0516. Special Collections & Archives, UC San Diego.) Tsembaga hand out salted pork fat to their allies, redistributing their environmental resources in efforts to forge key alliances. ([Pig festival, pig sacrifice, Tsembaga: behind ritual fence, decorated Tsembaga men wait to distribute salted pork fat to allies, November 1963]. Roy Rappaport Papers. MSS 0516. Special Collections & Archives, UC San Diego.)](/site/assets/files/2807/bb79878694_2-500x744.png)

The Shoshonean and Tsembaga communities' cognized models of the environment demonstrate the capacity of cultural activities as powerful mechanisms of environmental management, and vice versa. William Cronon's interdisciplinary book, "Uncommon Ground: Rethinking the human place in nature," provides a framework for understanding human interactions with the natural world6. To many environmental scientists, nature is an objective place, or a pristine state of being detached from human influences. It was quite unsettling for much of the class to read that our notions about nature and what constitutes the "natural" is inextricably linked to our individual cultural contexts. As Cronon says, "'Nature' is not so natural."

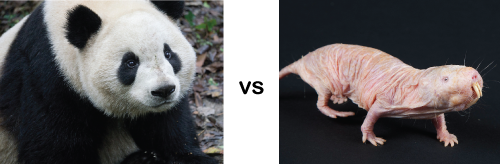

If each person sees the world through their own cultural or moral lens, then what authority do any of us have in deciding the inherent value of things in "nature"? This suggests that the environment is not the unambiguous force that we tend to think of, and such implications challenge seemingly neutral, unequivocal conservation efforts. The class questioned why certain species are preferred over others, like the charismatic panda (logo of the World Wide Fund for Nature) versus the naked mole rat. This discrepancy testifies to our contradictory meanings of nature, leaving animals and plants subjected to cultural whims that guide the temporal and spatial placement of natural areas.

As Cronon pointed out, constructions of nature are not natural, but the class overwhelmingly understood that differing cultural values can be harnessed to better frame a more inclusive environmentalism indicative of real attitudes and therefore more effective solutions. Erle Ellis' article, "Science Alone Won't Save the Earth. People Have to Do That," draws attention to another universal aspiration among humans- that of a better future7. We must drop the technical jargon and endeavor to create interdisciplinary approaches to problem solving with our combined vision of the future at the forefront of such efforts.

As the class concluded, bands of storms from hurricane Florence approached the outer banks of the Carolinas, only a few states away8. This storm, like last year's hurricane Irma, reflects the growing severity of weather events that more and more scientists chalk up to climate change. With a world population of 7.6 billion people and growing, the world's environmental problems are only getting worse. It will be deadly for us to continue divorcing human dimensions from anthropogenic climate change. By doing so we will all inevitably end up like Florida during a hurricane, twiddling our thumbs while the world wreaks havoc around us. Solutions are needed now more than ever, and they might be closer to home than you think, literally.

References

1. 'Nature'. English Oxford Living Dictionaries. Oxford, n.d.

2. Stephenson, R. Bruce. Visions of Eden: Environmentalism, Urban Planning, and City Building in St. Petersburg, Florida, 1900-1995. Columbus: Ohio State University Press, 1997.

3. Greenfieldboyce, Nell "Study: 634 Million People at Risk from Rising Seas." NPR, March 28, 2007.

4. Steward, Julian Haynes. The Great Basin Shoshonean Indians: An example of a family level of sociocultural integration. California Indian Library Collections, 1955.

5. Rappaport, Roy A. "Ritual regulation of environmental relations among a New Guinea people." Ethnology 6, no. 1 (1967): 254-264.

6. Cronon, William, ed. Uncommon ground: Rethinking the human place in nature. WW Norton & Company, 1996.

7. Ellis, Erle. "Science Alone Won't Save the Earth. People Have to Do That." The New York Times, August 11, 2018.

8. Zucchino, D. et al. "Hurricane Florence Live Updates: Storm 'Has Never Been More Dangerous.'" The New York Times, September 16, 2018.

Next Post > It’s game time! Board games that can help people ‘level up’ their capacity for transdisciplinary work

Comments

-

Morgan Ross 7 years ago

Alana, thank you for your great overview of the class discussion and material.

As you brought up, one of the most interesting parts of the class discussion was when we focused on how individuals each perceive the world differently. The idea that 'nature' is a summation of our individual perception and culture is eye-opening because it explains why so many people see humans as separate from the natural world. I think that as we continue to spiral into global destruction (of what we consider to be 'nature') our definition of nature will change as well. In a few generations, nature will be completely different.

-

Emily Nastase 7 years ago

I'm continually interested by the topic of perceived nature. Realistically I know that everyone experiences nature (and all aspects of the world) through unique lenses that only they can understand fully; and they are entitled to their opinions about their versions of nature. But I must admit, it was unsettling to hear Dr. Paolisso describe his nature experience at the gym on a computer screen. I sure hope that doesn't become the standard view of "nature" for future generations.

-

Tan Zou 7 years ago

Alana, it is a smart idea to cite definition in Oxford Dictionary! It tells us the mainstream definition of nature. I also like how you weave your memory of Florida into the blog. I found Cronon’s book so attractive that I bought it right after the class. The statement “nature as virtual reality” seems so advanced for me for a book published in 1996. Professor’s story “nature in the gym” reminds me of “Black Mirror: Fifteen Million Merits” (S01E02). Readings published later provide more and more questions, so it really makes me wonder: is it because the world we live in is creating more and more questions, or because we now know better what questions to ask?

-

Brian Scott 7 years ago

Interesting perspectives. I laughed out loud at some of your content, and some I am still pondering. Humans, in adopting the perspective that they are separate from nature, "defy the laws of the universe". Ha! I don't think there is any such universal law. But then again maybe that's what we are after all. Living beings spontaneously create order, violating the second law of thermodynamics. Our version of nature, mostly well manicured monocultures, is "unnaturally" ordered.

Maybe Mother Nature is just a jaded lover. We wanted to be close to her, but when we got there we tried to change her. We took out her mangroves and marshes that protected us. She's singing us a love song:

You must understand though the touch of your hand

Makes my pulse reactI've been taking on a new direction

But I have to say

I've been thinking about my own protection -

Shannon Hood 7 years ago

Thanks for such a thorough recap of a lively and interesting class period! And thanks for including the retro Florida postcard. It's interesting to notice how many cities and areas "brand" themselves as a great place to enjoy nature. However, as we discussed in class, nature means different things to different people and we experience and interact with it differently. Thanks for bringing in another example of somewhere that has capitalized on the idea of nature to entice visitors to the city. Ironic that in seeking to view nature, many people are looking to "get away from it all," but that same "nature" is what's driving people to the area. Great recap, thanks again!

-

Jessie Todd 7 years ago

I really enjoyed the different parts of your blog where you incorporated your own views and personal touches; it really makes it unique to you. I liked how you incorporated the naked mole rat versus the panda that we spoke on in class. It is nice to read those pieces we touched on that bring our topics to life. Your Florida example can allow any reader to make comparisons with places they have visited or think about how they viewed nature as they grew up. I know that I look back on what I perceived as nature and see how it has changed to what I think now.

-

Brendan Campbell 7 years ago

What I think is interesting about you bringing up the increased migration to Florida being analogous to California is that a large portion of Florida migrants are originally from New Jersey. New Jersey has similar attributes as Florida but have a more utilitarian flavor to them. New Jersey has beaches, but they are surrounded by dense development or they are used for shipyards which are not nearly as aesthetic. On the other side, Florida is more prone to disaster like you said (even though New Jersey has had some bad storms in the past). It looks to me like people are even jumping to more natural feeling locations despite the hazards, even if they come from a place similar that is theoretically safer.

Even I moved from New Jersey to the Eastern Shore where natural settings are dominant although some of the features again are similar. I think I run into more turkeys and deer than I do people down here. The danger where I live in Maryland is flooding, the towns deeper into the Eastern Shore flood almost daily which does not happen in New Jersey due to the higher elevation but my rationale is that I live in a scenic area where I can drive out to the middle of nowhere at a given moment and be in peace. I never made this connection until now and it connects well with this theme. Interesting brain food. -

Matthew Wilfong 7 years ago

Alana,

Great summary of the class. Wish I could have been there to take part, re-watching the lecture was not quite the same as taking part in the discussion itself.

I think Ellis really got after the inherent inability of scientists to cross over and reach mainstream audiences. Scientists, in general, love to do their work and keep to themselves, but in the environmental realm, the opposite needs to occur.

Ellis also importantly highlighted that trade-offs and compromises is the only way forward in human-environment relations. A tough, but undoubtedly true remark that remains the only way towards a more sustainable relationship.

-

Michael J. Paolisso 7 years ago

Very interesting and thoughtful and creative. I enjoyed seeing the lecture being recast in this blog format with a refreshing framing. Well done.

-

Natalie Peyronnin 7 years ago

Wow! Great post and use of imagery! Even though I was there, your writing style and use of humor captured my attention throughout the blog. The evolution of anthropology from armchair analysis to immersion was really interesting.