A polemic against coupled human and natural systems, boundary spanning, and transdisciplinarity:

Suzanne Webster ·An existential appeal to "Shake things up" in socioecological systems research

Earlier this month, I attended a three-day international symposium called "Boundary Spanning: Advances in Socio-Environmental Systems Research," which was hosted by the National Socio-Environmental Synthesis Center (SESYNC) in Annapolis. About 250 scholars representing a diversity of academic disciplines and 23 countries convened to discuss socio-environmental systems research, or the study of "tightly linked social and biophysical subsystems that mutually influence one another." The conference was organized into three major themes that centered on socio-environmental systems under stress, in transition, and by design. Every attendee contributed either an oral or poster presentation to the symposium, and many speakers discussed topics of great interest to me, including the politics of coproduction, the multidimensionality of environmental value, the social authority of scientific knowledge, and the role of science in political and social change.

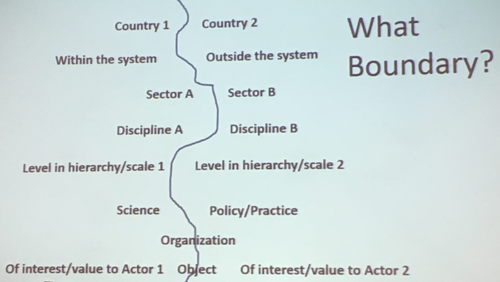

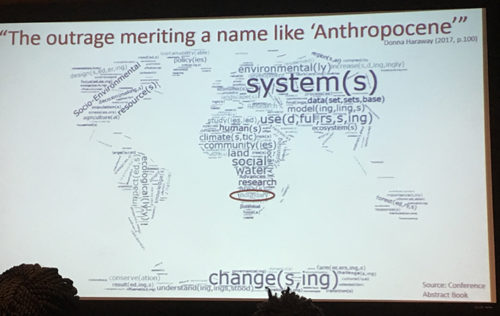

The interdisciplinary field of socio-environmental systems science has popularized in recent years as researchers increasingly recognize the value of integrating multiple sources of knowledge and research approaches when addressing complex environmental problems. Scholars in this field often strive to span boundaries that separate data, social actors, and other components of social and environmental systems, in order to assimilate information that will contribute towards a more holistic understanding of a system, as a whole. Boundaries exist in a variety of forms, such as the border between two countries, the division between two academic departments or disciplines, the distinction between groups of people like academics and practitioners, or the separation of nature and culture. In socio-environmental systems research, we span boundaries when we compare discrete GIS layers containing either sociological or environmental data, when we compile knowledge from multiple stakeholders who represent homogenous divergent interest groups, or when we construct networks and symmetric box and arrow diagrams that depict social and environmental systems as delineated functional components.

This conference experience made me question whether the field of "socio-environmental systems" research might be better served by rejecting boundaries, rather than spanning them. Although all of these boundary spanning approaches are no doubt an improvement on monodisciplinary research and problem-solving frameworks, distinctions within socio-environmental systems often collapse when real world phenomena don't fit nicely into our tangible categories. Therefore, when studying a "coupled" system, I wonder how productive is it to first conceptualize or model the social and ecological systems separately, rather than conceptualizing one intimately interconnected system from the beginning? In other words, to what extent does our existing disciplinary vocabulary and research architectures influence the way we, as academics, study systems and solve socioecological problems? Are we captured by existing structures and outdated language that reinforce the very boundaries we seek to span?

I left the conference with my head spinning, filled with a slew of seemingly unanswerable questions. What distinguishes nature from not-nature or culture? How can we differentiate something as belonging to the realm of the environment vs. being part of society? What delineates my identity as an environmental scientist from that of a social scientist or an interdisciplinary researcher? As I racked my brain for answers, I felt increasingly disoriented as the distinctions and boundaries that many consider the backbone of my field of study began to feel increasingly arbitrary.

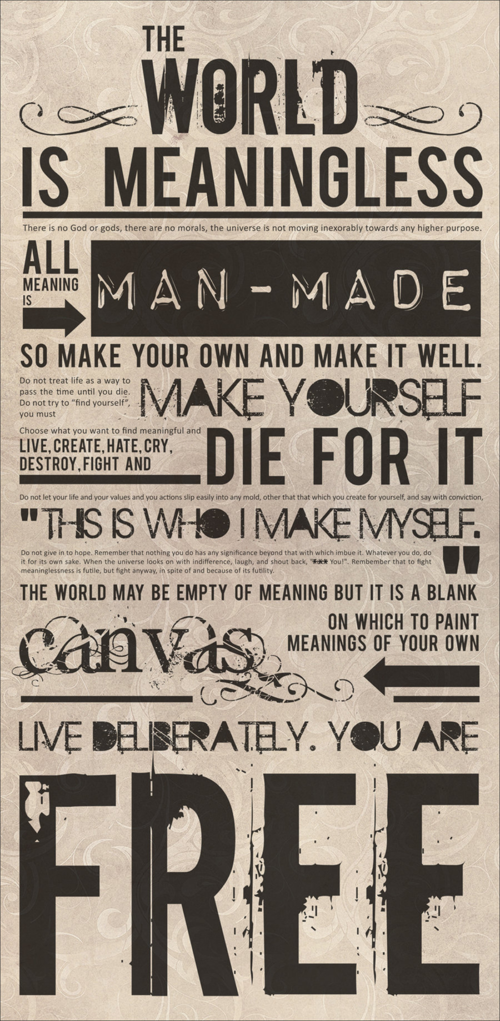

I thought back to my high school literature class discussions on existentialism, a concept that I couldn't quite wrap my head around at the time, but that is now holding more meaning to me as a mid-career graduate student. A key theory of the existentialist movement is that existence precedes essence. The world exists before we try to make sense of everything. There are no absolutes and there is no objectivity, which means that there are endless possibilities for how humans can choose to define themselves and seek out order in their surroundings. An individual can live authentically by exercising their freedom to create their own sense of meaning, which becomes the basis of their decisions and self-conceived identity. Conversely, an individual lives in "bad faith" when they refuse to reject determinism and instead blindly accept established rules of compartmentalizing the world and conceptualizing meaning instead of appreciating life as random and absurd. Bad faith causes individuals to feel frustrated with a world that refuses to obey their sense of order. Existentialists believe that people close themselves off to change in order to avoid facing a paralyzing abundance of freedom. This paralysis forces people to accept an unconvincing worldview and constantly lie to convince themselves that they don't have other options for organizing their world and developing their own perceptions.

Boundary-spanning scientists and science communicators can learn a great deal from this philosophical school of thought. We must first acknowledge that the way that scientists understand and compartmentalize our world is arbitrary, and then we must recognize that our current understanding of the world is not necessarily the best-suited possibility for solving complex problems. As we strive to span boundaries, it would do us good to pause for a moment of reflection, humility, and curiosity, and question the boundaries that academia has, as an institution, overwhelmingly accepted as certain. What defining properties make a science either social or natural? What characteristics separate a scientist from a stakeholder? Can something simultaneously belong to a human and a natural system?

These questions are difficult to answer because the world, like the complex problems that we research, is messy and not composed of neat compartments and dichotomies. Scientists live in bad faith when we confine ourselves to one way of understanding the world. One example of this is mainstream conservationism, which conceptualizes people as separate and distinctive to nature and idolizes "pristine" ecosystems uninfected by humans. Our understanding of the world affects the way we prescribe value and influences our ability to conduct research and solve "wicked" problems. We must remind ourselves that there is not one objectively correct way of perceiving the world, and therefore we can (and perhaps should) create new ways of navigating science instead of relying on previous ways of understanding. So how can boundary spanners take steps towards living more authentically?

To start, do not allow disciplines to constrain our discourse. This is much deeper than simply avoiding disciplinary jargon. Sometimes the boundaries and words we use to navigate our world are just not useful for solving particular complex transdisciplinary problems. Instead of patchworking disciplinary approaches together and grasping at the edges of established fields of study, perhaps it would be more useful to build a new, integrative problem-solving field from the ground up. An alternative approach could free us from existing vocabulary that grounds us in home disciplines and perpetuates a worldview of dichotomies. During her plenary presentation, Dr. Banu Subramaniam challenged us to consider "moving from studying nature and culture as separate realms of knowledge, to creating more interdisciplinary frameworks for studying the many socioenvironmental borderlands of naturecultures." In order to do this, we could try conducting collaborative research that centers our dialogue around a particular problem of interest, rather than around a discipline or set of disciplines.

Dr. Ray Hilborn provided an example of how this strategy might work in practice. Many interdisciplinary research teams are investigating the growing societal problem of sustainable protein production; however, most research on this problem is nested within one of three distinct communities of academia and practice—agriculture, aquaculture, and fisheries. Scholars and practitioners rarely collaborate across these wider disciplines even though these systems are connected to solving the common problem of protein production, as well as deeply intertwined with one another. Dr. Hilborn suggests that researchers come together and ask "Ok, societally we want to raise the most amount of protein with the least amount of environmental impact. How do we do that?" Framing the research as a holistic problem-solving endeavor, rather than a socioecological systems effort, could remove some of academia's baggage and structure, and free up collaborators to exert more of their creative energies towards coming up with new solutions rather than towards reconciling disciplinary differences.

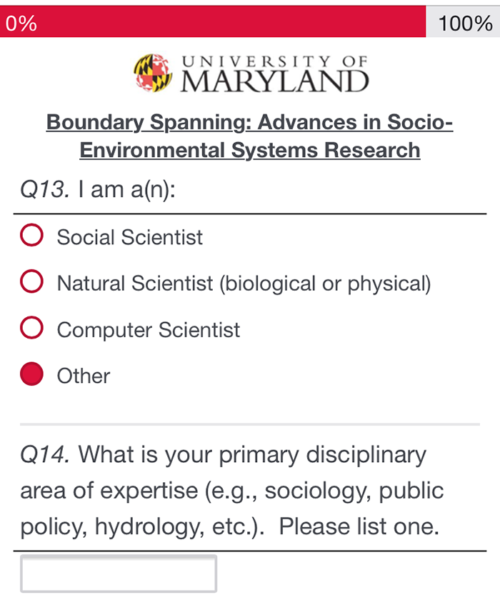

Second, let's try to define ourselves based on our motivations, instead of our boundaries. At the start of her keynote plenary, Dr. Susanne Moser asked everyone to remove our conference nametags, stand up, walk ten steps, and introduce ourselves to someone without sharing our position, institution, or discipline. It was very awkward. Dr. Moser then encouraged us to be self-reflective, asking, "How often do you introduce yourself to others by telling them where your boundary ends?" In the words of existentialists, why do we allow ourselves or other people to objectify and essentialize us by putting us in a box and defining who we are? Why do researchers continually allow and perpetuate this divisive language? An example of this objectification was even found within the conference survey, which asked attendees to self-identify as either a social, natural, or computer scientist. Frankly, I found it a bit irritating that such an interdisciplinary group of thinkers should be asked to box ourselves into one of these categories. Who decided that it would be useful to boil us all down into one of these particular categories? It turns out that this particular survey item is an NSF-mandated question. This divisive language is institutionally ingrained and exerts top-down control over our research content and funding, as well as over our identities as researchers. After our awkward initial introductions, Dr. Moser asked us to try again, and this time tell our partner what we do and what motivates us to do it. These conversations were much richer and it was so interesting to hear people reflecting on and sharing their deep motivations, in many cases for what seemed like the first time in years. When we let our deep motivations anchor us, I think this provides a much more authentic, inviting, and productive foundation for collaboration.

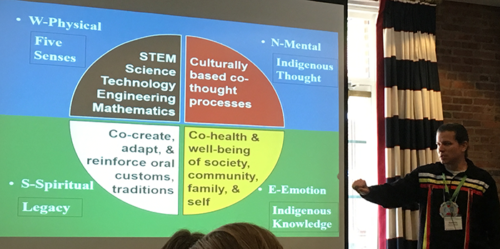

Next, we need to deliberately collaborate with people who have different worldviews than ourselves. Researchers need to recognize that academic compartmentalization of the world into nature and culture or humans and the environment stems from Western philosophy. Although pervasive in academia, this dichotomization and resulting disciplinary speciation is arguably a relatively new phenomenon, and it is not universal. If modern academics want to explore other ways of conceptualizing and studying our world, we need not reinvent the wheel; rather we can diversify and expand academic discourse by partnering with or empowering Eastern or indigenous scholars and learning from their more holistic worldviews. We can also co-create new scientific knowledge in collaboration with nonacademic partners, such as citizen scientists or farmers, who have rich environmental knowledge and worldviews that stem from their own experiences living and working with "nature".

Finally, we should embrace our freedom and power to redefine what is valuable. Our concept of value stems from the way that we perceive the world. We can answer questions like "What types of information or knowledge constitutes valuable science?" or "What makes a scientist successful?" The institution of academia has, over time, suggested various answers to these questions, and many academics fall victim to social mimicry and unquestioningly accept these suggestions as their personal truth. For example, for many natural scientists, valuable science is objective knowledge that is testable, quantifiable, peer-reviewed, and discoverable using the scientific method, while successful scientists are those who hold a tenure-track position in an academic department and are well-known to others in their disciplinary field. If we, as a scientific community, legitimize only this way of thinking about our world, and more specifically, about scientific knowledge production, we limit our ability to truly span boundaries while also discrediting other forms of knowing. Perhaps it is time to support other "research architecture" designs, such as one that values qualitative data, supports knowledge integration that transcends traditional disciplines, and breaks divides between researchers and non-academic communities. The important thing to remember is that, as individual scientists, we can and should define for ourselves what good science looks like, and what it means to be successful, and then strive to live authentically based on our own values. During the Boundary Spanning Reflections Panel at the end of the conference, Dr. Kendra McSweeney offered attendees some inspirational words of advice when she encouraged us to "Be bold, test the counterfactuals, the radical propositions, the things that people say can't be done. Shake things up!"

Resources

1. Foucault, Michel. "The order of discourse." Social science information 10.2 (1971): 7-30.

2. Haider, L. Jamila, et al. "The undisciplinary journey: early-career perspectives in sustainability science." Sustainability Science 13.1 (2018): 191-204.

3. Kierkegaard, Søren. "The Concept of Anxiety" (1844).

4. Osborne, Peter. "Problematizing disciplinarity, transdisciplinary problematics." Theory, culture & society 32.5-6 (2015): 3-35.

5. Pernecky, Tomas, Ana MarÃa Munar, and Brian Wheeller. "Existential postdisciplinarity: Personal journeys into tourism, art, and freedom." Tourism Analysis 21.4 (2016): 389-401.

6. Sartre, Jean-Paul. "Being and Nothingness: An Essay on Phenomenological Ontology." (1956).

About the author

Suzanne Webster

Suzi Webster is a PhD Candidate at UMCES. Suzi's dissertation research investigates stakeholder perspectives on how citizen science can contribute to scientific research that informs collaborative and innovative environmental management decisions. Her work provides evidence-based recommendations for expanded public engagement in environmental science and management in the Chesapeake Bay and beyond. Suzi is currently a Knauss Marine Policy Fellow, and she works in NOAA’s Technology Partnerships Office as their first Stakeholder Engagement and Communications Specialist.

Previously, Suzi worked as a Graduate Assistant at IAN for six years. During her time at IAN, she contributed to various communications products, led an effort to create a citizen science monitoring program, and assisted in developing and teaching a variety of graduate- and professional-level courses relating to environmental management, science communication, and interdisciplinary environmental research. Before joining IAN, Suzi worked as a research assistant at the Marine Biological Laboratory in Woods Hole, MA and received a B.S. in Biology and Anthropology from the University of Notre Dame.