A Time to Krill

Kate Petersen ·

“The web of life ….” “The evolutionary tree ….” These are phrases used so often they approach cliché, but they also capture, in living metaphor, a fundamental truth: that all life exists in relationship. In mangrove forests, these stock ecology textbook phrases seemingly quicken in the cries and shocks of color that decorate a bird and primate-filled canopy. Thick trunks diverge into a rigid tangle of stilt-like roots that plunge into blue-green saline water. Under the surface, crocodiles, sharks, manatees, fish, crabs, rays, and all manner of other fauna hunt, mate, shelter, and otherwise live their aquatic lives. Dynamic tidal flows lay bare the twisted root structures, hours before the backdrop of incredible diversity. Then the sea returns again, saturating the landscape, repopulated with the familiar cacophony of life.

Mangrove Forests

Mangroves develop in estuaries, where rivers complete their long journey to the sea. Inland sediment is deposited here and the mangrove tree structures prevent ocean erosion, stabilizing the coastline. Humans have long relied on mangroves for subsistence fishing and selective harvest of tree parts for wood, herbalism, and hide tanning materials. But now this particular intersection in the vast web of life is in trouble, a nearly archetypal theme in modern global ecology. Cut, burned, poisoned, and choked with (or alternately starved of) sediment, mangrove forests are being obliterated. According to the International Union for the Conservation of Nature, fifty percent of mangrove forests have been cleared worldwide in the last fifty years to support coastline development, agriculture, textile production, and aquaculture.

Shrimp Farming in Ecuador

In Ecuador, home to the tallest mangrove trees in the world (forty meters), Dr. Stuart Hamilton of Salisbury University studies the ecological and sociological impacts of mangrove decline. His work emphasizes the impact of shrimp aquaculture, an industry that has exploded in Ecuador over the last forty years. After clearing mangrove forests, farmers cultivate shrimp in large pits dug into the sediment. The pits are crowded and subject to disease, so the farmers infuse them with antibiotics and pesticides. When they become too toxic and diseased to be viable, farmers clear more mangroves and dig more pits, leaving thousands of acres of abandoned, toxic shrimp pits behind them. Remediation of these abandoned shrimp farms to allow for mangrove replanting would require deconstructing levees and manually removing huge quantities of toxic sediment.

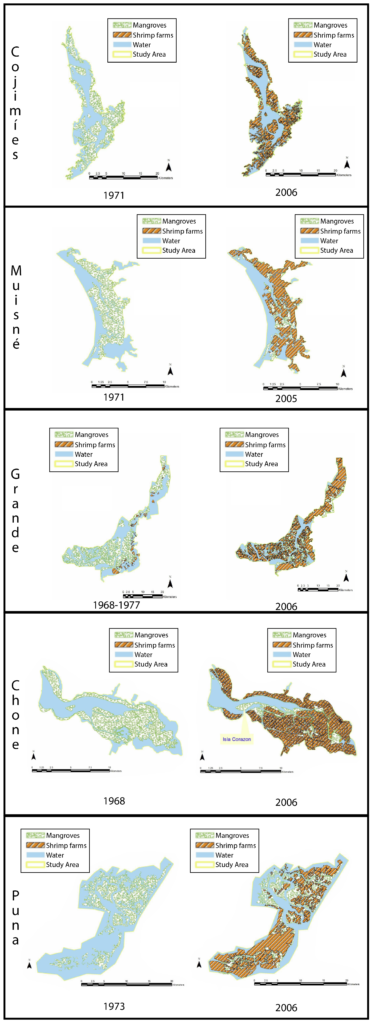

Loss

Dr. Hamilton has documented the history and trajectory of Ecuadorian mangrove deforestation by assembling and comparing a roughly sixty-year sequence of topographical maps, aerial photographs, and satellite images of coastal estuaries. His findings are shocking. Eighty-nine percent of Ecuadorian mangrove forests are gone. Fifty-three percent of the loss was driven by shrimp farming. According to Dr. Hamilton, “The estuaries in which the mangrove forests once resided are no longer functioning estuaries due to issues related to declines in water quality, increases in sedimentation, and decreases in the native flora and fauna that used to be present. The mangroves were the keystone species that drove the entire estuarine ecosystem in Ecuador.” He identified additional ecological consequences for this destruction as accelerated erosion, the release of forty-seven million tons of carbon, and the loss of one hundred thousand tons of carbon sequestration potential.

Dr. Hamilton’s team conducted interviews with area residents to document the impacts of these losses on human populations. Residents reported that local species extinction undermines traditional subsistence fishing, decreasing local food availability. Salt leaching from ocean incursion destroys agricultural fields. Traditional timber use (poles, boats, tannin), herbalism, and honey collection are impacted or eliminated. Perhaps the most extraordinary loss of resource access results from the way the farms are structured and maintained. Because mangrove forested areas are, by nature, beneath the tideline, farmers build large levees to block tidal flow. In this way, they can maintain farms in areas that used to be underwater, creating a new functional shoreline. Since the farms are often under guard, and cannot be crossed, some residents can no longer access estuary water at all.

Dr. Hamilton summarized the “disastrous” economic transition that has occurred, stating that, “Clearing … mangrove forests has resulted in the collapse of a highly-productive and economically valuable mangrove ecosystem. A wild fishery that once provided livelihood opportunities and food security to tens of thousands of local residents has been commodified into an export-orientated industry that generates large amounts of wealth [for relatively few people]. Few if any replacement economic opportunities are provided for local residents by the shrimp farm industry, whereas the prior mangrove-driven economy was almost entirely local in the benefits produced.”

Ecuador is the second-largest supplier of shrimp to the United States.

Revelation

The final book of the Bible, the Book of Revelation, describes the end of the world, a fiery, violent cataclysm in which all the world’s dead are resurrected to finally encounter a vengeful divinity. Whether this can be considered a happy ending is a matter of perspective. Revelation tells us that the Tree of Life, originally described during the creation of the heavens and the earth, survives Armageddon. He who has an ear, let him hear what the Spirit says …. To him who overcomes, I will give to eat of the Tree of Life, which is in the Paradise of God. Here, again, is living metaphor; respite from the end times is found in relationship. Life exists in relationship. Dr. Hamilton’s work demonstrates in potent detail that humans do not have a choice of whether to be in relationship with mangrove forests, only how. Hopefully, this will be a revelation.