Achieving Sustainability at the Nexus of Science, Advocacy, and Policy

Emily Russ, Aimee Hoover, Whitney Hoot · | Science Communication | Applying Science | 6 commentsEmily Russ, Aimee Hoover, Whitney Hoot

Nearly 500 years ago, Nicholas Copernicus determined the Earth revolved around the sun. Scientists and philosophers hotly contested this radical idea in the sixteenth century, but further research eventually confirmed Copernicus' observations. This globally accepted understanding, or paradigm, that the sun is the center of our solar system was the result of this scientific effort. Since Copernicus's discovery and up through the twentieth century, there have been nine additional paradigm shifts where scientific findings have been effectively communicated and have, ultimately, revolutionized our understanding of physical, chemical, and biological processes (Dennison 2008).

Currently, we are plagued with issues such as rapid population growth and increasing affluence, leading to over-exploitation of non-renewable resources and environmental degradation; however, we are on the cusp of a paradigm shift toward sustainability, where science can be used to guide sustainable management of our natural resources, and potentially reverse environmental damage (Dennison 2008). Communication between scientists, policy makers, and relevant stakeholders facilitate this shift (Cash et al. 2003).

Misinterpretation is a major obstacle to science communication: people often misconstrue the term sustainability. People tend to associate 'sustainability' with a liberal political agenda or assume it conflicts with religious dogma. Therefore, it is essential to have a coherent and explicit definition that is consistent across different disciplines. Merriam-Webster defines 'sustainable' as the ability to be used without being completely used up or destroyed (2015). Sustainable environmental solutions are widely sought after in both academic and political realms, especially in heavily populated coastal areas. The Chesapeake Bay is among these coastal systems that experiences a myriad of environmental issues including: eutrophication because of land use changes (Dennison 2008); marsh inundation due to the combination of sea level rise, land subsidence, and reduced sediment (Kirwan and Megonigal, 2013); and the loss of oysters to disease and overharvesting (Boesch et al. 2001).

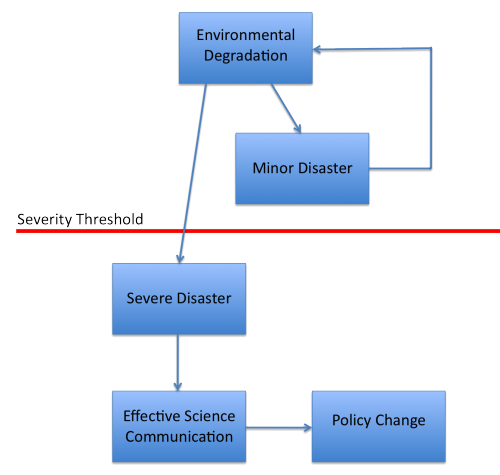

Although scientific communities recognize these environmental issues, it can be difficult to mobilize policy change due to uncertainties associated with the findings. However, large disaster events can be effective in catalyzing legislative change. For example, the Oil Pollution Control Act (1990) was passed after the Exxon Valdez oil spill in Alaska and the Montreal Protocol (1987) was agreed upon to phase out ozone depleting substances after the ozone hole was discovered. In both these cases a severity threshold was crossed where people acknowledged the consequences of these disasters and became more amenable to policy changes.

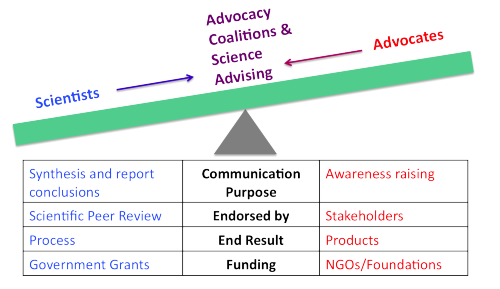

It is impractical to wait for an environmental disaster in order to adopt more sustainable management practices. Therefore, scientists and boundary organizations must effectively communicate science to managers, government, and other stakeholders in order to generate proactive change (Cash et al. 2003). Conceptually, we can view science and advocacy as endpoints between recognizing and understanding a problem and initiating change, and thus these sectors have different objectives. It is naïve to assume that scientists are completely disconnected from advocacy because personal convictions often motivate some aspect of their research and experience. However, scientists can lose credibility when they use science to leverage their beliefs and must find a neutral balance (Pielke Jr. 2007).

In order to initiate a paradigm shift toward sustainability, scientists need to step outside their job descriptions to inform a nonacademic community. Although different goals may drive scientists to achieve success as a credible peer-reviewed researcher (Pasteur's Quadrant), their synthesized data and conclusions need to be communicated to policy advocates to bring about legislative change. As described earlier, disconnects often form between advocating a cause and unbiased scientific research, so advocacy coalitions can be utilized to work across these gaps. These groups encourage a synergistic relationship between scientists, who present evidence of environmental issues and suggest possible solutions, and advocates, who work to bring these solutions to action.

The effective integration of science and politics is complex and multidimensional. One of the main hurdles is that science and politics have different endgames; scientists are tasked with finding truth, while political figures are interested in maintaining power. However, there is no such thing as absolute truth and power. Therefore, to maintain credibility, scientists should strive to always tell the truth about their data and not be selective in what they show, always offering alternative views to an issue. Scientists and policy advocates should then maintain an open line of communication in order to optimize science and action.

References:

- Boesch, D., Burreson, E., Dennison, W., Houde, E., Kemp, M., Kennedy, V., Newell, R., Paynter, K., Orth, R., and Ulanowicz, R. (2001). Factors in the decline of coastal ecosystems. Science,293(5535): 1589-1591. [pdf]

- Cash, D. W., Clark, W. C., Alcock, F., Dickson, N. M., Eckley, N., Guston, D. H., Jager, J., and Mitchell, R. B. (2003). Knowledge systems for sustainable development. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 100(14): 8086-8091. [pdf]

- Dennison, W. C. (2008). Environmental problem solving in coastal ecosystems: A paradigm shift to sustainability. Estuarine Coastal and Shelf Science, 77: 185-196. [pdf]

- Kirwan, M. L. and Megonigal, J. P. (2013). Tidal wetland stability in the face of human impacts and sea-level rise. Nature, 504(7478): 53-60. [pdf]

- Pielke Jr., R. A. (2007). The Honest Broker: Making Sense of Science in Policy and Politics. New York, NY: Cambridge University Press.

- Sustainable. (2015). In Merriam-Webster.com. Retrieved February 12, 2015, from http://www.merriam-webster.com/dictionary/sustainable

Next Post > Talking about moose and climate change in snowy Massachusetts

Comments

-

Detbra Rosales 11 years ago

Yes i agree with you Melanie, scientist need to address uncertainty in order to make changes and uncertainty can be linked to the precautionary principle. For example to get a new medicine on the market there many hurdles and loops researchers need to jump through to get the FDA approval. This all stems from the uncertainty of the new drugs. There should be precaution but not to the extent that nothing gets accomplished. Perhaps the distrust can be linked to new research and information that contradicts the original research? for example i remember reading drinking coffee is bad for you and then other studies state that drinking coffee is actually good for your health and metabolism.

-

Melanie Jackson 11 years ago

I wonder if much of the public's distrust in scientists today stems from the time it takes for us to "mobilize policy change". Uncertainty is definitely a hurdle that we need to assess in order to get things done.

-

Whitney Hoot 11 years ago

I'm really intrigued by the idea of the severity threshold and I wonder how it could be defined and quantified. It would be interesting to conduct a study of disasters or other events that crossed the severity threshold and see what they have in common - Geographic scale of influence? Total value of property damage? Number of lives lost or injuries? Duration or intensity of domestic and international media coverage? Additionally, how long does the "change" last following the event? What qualities does a disaster or event need to have in order to have long-term impacts on the public's views and values? For example, what has to happen before the most stubborn climate change deniers change their minds?

People who are directly impacted by a catastrophic event don't forget it easily; FEMA is still processing flood insurance claims almost 2 1/2 years after Hurricane Sandy. However, the general public seems to have a more ephemeral attention span. In defining a severity threshold, we could determine how much attention (from the public and media) needs to be generated (and for how long) to result in effective science communication and policy change.

-

Rebeca Peters 11 years ago

Melanie, I do think that part of the public's distrust in scientists may stem from the time it takes for us to implement policy change. When I was in Florida sitting in on a meeting for the Our Florida Reef program with stakeholders from various organizations working together to create management recommendations for the South Florida reef tract. One of their concerns was how long the process was going to take along with the uncertainty about whether agencies would voluntarily implement their recommendations. I think it is important to educate people on the process of policy change, which the Our Florida Reef program did in order to alleviate some of the uncertainties. It is normally a lengthy process that takes time to study the problem, come up with a plan of action, solicit public comments, and refine their action plans based on those comments. For example NMFS added new corals to the endangered spices list in 2014, however the proposal started in 2011. Maybe if the public was educated on the process there could be less distrust.

-

Adriane Michaelis 11 years ago

When communicating science I think it's also important to be aware of not only misinterpretation of terms, as described above, but also misinterpretation of data. It is very easy to pull a number, figure, or table from an article or talk and present it in a way that suits a certain interest, even if the comprehensive dataset or study doesn't support that point.

I'm not sure that this is something that can ever be avoided or eliminated, but it is worthy of note; by planning for the possible manipulation and incorporation of data, scientists can and should attempt to communicate clearly and completely, possibly minimizing opportunities to misinterpret.

-

mouhamed 10 years ago

Interesting to read such Article, Thank you