Building coastal resilience through stories

Bill Nuttle · | Science Communication | Applying Science |Coastal scientists have an important role helping communities become more resilient by telling people what changes can be expected from climate change and sea level rise. But, how can you tell people about change that is coming, in a way that makes it tangible for people and motivates them to act, when the extent of that change goes beyond what many can even imagine. Accelerating sea level rise presents unprecedented challenges for communities that, for the most part, they are utterly unprepared to deal with. For example, the community of Kivalina, Alaska, is confronted by the likelihood that the island it has occupied for centuries will disappear within a decade. Worldwide, densely-populated modern cities, like Calcutta, Miami, Shanghai, and New York, are threatened. Within the lifetime of a young adult, seawater will flood sewers and subway tunnels and high tide will bring several feet of water standing in the streets.

Communication is an essential part of science, and there is a wealth of experience to guide scientists about how to disseminate results of their research. But, to be successful at preparing coastal communities for change, people must assimilate information from scientists into their “adaptive unconscious,” where it becomes part of the calculations that guide decision-making. Malcolm Gladwell describes the adaptive unconscious as a kind of internal computer that we use for processing the mass of data we need to function but without consciously thinking about it. Others might call it our intuition or gut instinct.

According to Randy Olson, the core communication challenge for scientists in all disciplines is how to move what scientists know in their head (the seat of abstract knowledge and rational thought) down through the heart (the seat of emotional intelligence) and into the gut (the seat of intuitive understanding and spontaneous action). Olson is a scientist-turned-filmmaker who now works with other scientists improve their communication skills. His advice to scientists centers on telling stories. Story-telling is a sure way to connect with a broad audience, as the success of Hollywood blockbuster movies shows.

In his book, “Connection: Hollywood Storytelling Meets Critical Thinking.” Randy Olson presents a set of practical tools for creating stories that work. Here, I illustrate three of the most important lessons: structure, sympathy, and specifics, with examples taken from two scientists, Charles Darwin and Carl Sagan, and John Barry a science historian. These authors succeeded in connecting with a broad audience by using same techniques that Olson later learned from film making. And, this fact reinforces the point that these techniques are the key to effective communication in science and generally, not just in Hollywood.

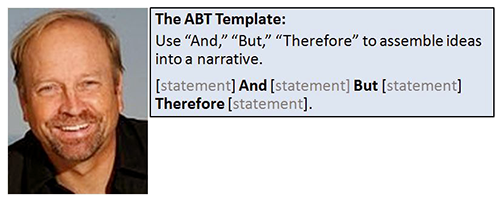

Structure — tell stories to grab and hold your reader’s attention

Story-telling works, because the human brain is hard-wired to respond to information presented in story form. Stories have a particular structure — a beginning, a middle, and an end. Olson created the ABT template (And, But, Therefore) to help people give their ideas the structure of a story. The first part of a story, the beginning, consists of a number of statements connected by the word “and.” These statements add to each other to establish the background for the story. The appearance of the word “but” or “however” introducing a statement signals that what follows is different than what came before. The word “but” introduces conflict; something has happened, and the action of the middle of the story starts to unfold. “Therefore” introduces the end of the story; the conflict is resolved; conclusions are drawn, and the world settles into a new state.

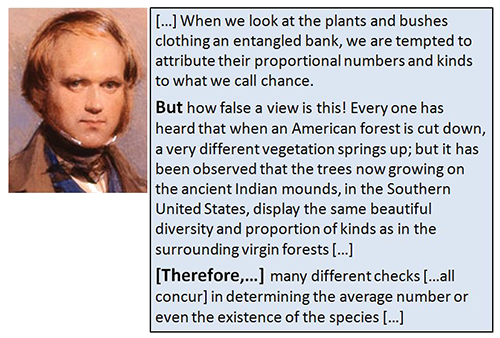

The first example, from Charles Darwin’s “On the Origin of Species,” demonstrates that structuring ideas into a story is not only compatible with scientific writing but enhances it. The format of a scientific research paper follows a classic structure: introduction, methods, results and discussion, conclusions. Very little deviation is tolerated. Opportunities for story telling occur within this structure. In particular, the introduction lends itself naturally to story-telling — a review of prior knowledge, punctuated [but] by an insight, which [therefore] leads to a new hypothesis.

This is what Darwin does in “On the Origin of Species.” In the most familiar passage from that book, Darwin uses the metaphor of an overgrown, entangled bank of vegetation as a metaphor for the complexity of the natural world. The appearance of this metaphor in the last paragraph echoes its use in a paragraph near the end of the third chapter, where Darwin first states his theory of natural selection. In that paragraph, which is outlined above, Darwin actually uses two supporting stories — one on changes to the structure of the forest of North America and one on a handful of feathers thrown to the ground — to build the larger story of natural selection. The effect is to engage the reader through their imagination, to supply details supporting Darwin’s argument.

Sympathy — connect by appealing to the heart and the gut

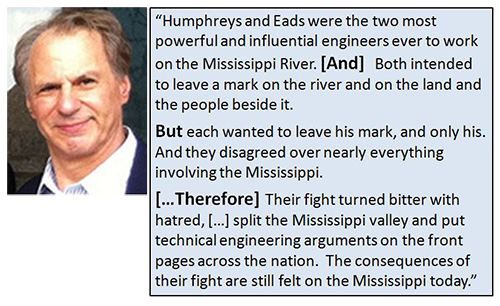

Sometimes, it is necessary to look beyond the science to find the story to that engages with the sympathies of the reader. That was the challenge that historian John Barry encountered in writing his book , “Rising Tide.” The subject of the book, the Great Mississippi Flood of 1927, overflows with human interest. But, at its core is a conflict between different theories of river hydraulics. No matter how you cut it a story about the interplay between momentum flux, sedimentation and the threshold of incipient motion is going to be a hard slog for most readers.

Barry’s solution is to write instead about the competition between two engineers who championed different approaches for managing the Mississippi River. Andrew A. Humphreys was an officer in the U.S. Army and an engineer trained in mathematics and science at West Point. By contrast, James Buchanan Eads was a self-taught engineer and businessman who became wealthy building a successful marine salvage business on the Mississippi River. Both men argued their conflicting positions based on the underlying science. Barry uses the story of their conflict to convey information uncertainties in the science of river hydraulics that still confuse efforts to manage the lower Mississippi River and its impact on the coast.

Specific — provide details to make it tangible

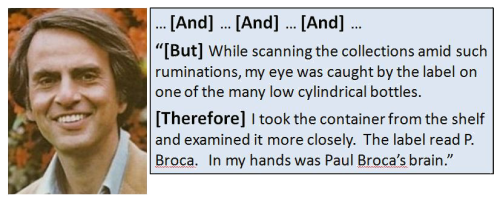

Science deals with topics encountered in science often are far from the everyday experience. The can present an obstacle to communication, but the strangeness of science can also be exploited capture a readers’ interest. The astronomer Carl Sagan exploited our inherent curiosity about the universe that we can glimpse in the night sky to build a career as a writer and media celebrity in the 1980s. Today, Neil deGrasse Tyson hosts a remake of Sagan’s television program “Cosmos” and plays a similar role as the public face of science. The key to success in taking this approach is to feed the reader’s interest by providing a wealth of specific detail.

This example of the use of detail is from the introduction to Sagan’s essay “Broca’s Brain,” which is part of a collection of essays published under the same title. Paul Broca was a physician who lived in Paris during the 19th century. Sagan uses the story of a visit to the Museum of Man to introduce his reader to Broca and draw them back into the early days of anthropological research. Sagan’s visit begins at a place accessible to the imagination of many readers, outside the museum within view of the Eiffel Tower. The story of his visit takes the reader, in stages, through the exhibit hall, into the backrooms where scientists are studying materials in the collection, and from there into storage areas that hold different materials used in past studies. And, so on into the depths of the museum until, finally, the reader is figuratively peering over Sagan’s shoulder as he reads the label on a dusty bottle and begins …

Stories build coastal resilience

The resilience of coastal communities will be built by scientists telling stories similar to these. The stories will tell people about the science that underlies projections of future change, the remaining uncertainties, and the controversies that arise from them. But, the real challenge for scientists will be in telling stories that make the future of the coast tangible, stories that transport their audience from the familiar present-day into a strange, new future.