Chesapeake Bay SAV Watchers: A new citizen science program for monitoring Bay grasses

Suzanne Webster · | Learning Science |Last month we put the finishing touches on a year-long effort to develop a monitoring program for volunteers who collect data on submerged aquatic vegetation (SAV) throughout the Chesapeake Bay. The new program is called Chesapeake Bay SAV Watchers. Throughout this project, we collaborated with various stakeholders, including SAV experts, volunteer monitoring coordinators, and citizen scientists. Our goal was to design a monitoring protocol and certification program that generates useful data for professional scientists, while also providing an engaging and educational experience for volunteers.

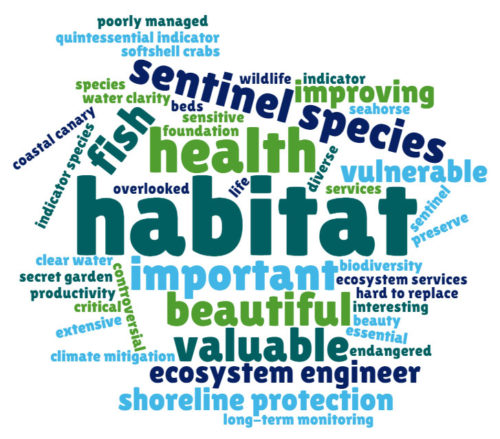

Monitoring SAV in the Chesapeake Bay is important because SAV plays an important role in the Bay ecosystem. SAV provides crucial habitat and nourishment for animals, sequesters carbon and nutrients, anchors and oxidizes sediments, protects shorelines from erosion, and increases water clarity. Furthermore, because SAV is particularly sensitive to changes in water quality, scientists and mangers often look at the status of SAV as an indicator of changes in the environment or in overall ecosystem health. Unfortunately, the Bay has experienced a catastrophic loss of SAV in recent decades due to various factors including nutrient pollution, sea level rise, and increased water turbidity.

Scientists and managers have remained committed

to achieving SAV restoration goals ever since they were first established in

the first Chesapeake Bay Watershed Agreement (1983). Every year, scientists use aerial surveys to create a map of SAV in the Bay, and this

map directly informs policy and management decisions. Furthermore, a SAV

scientific synthesis team was formed to closely

investigate how long-term trends in Bay SAV distribution are related to human

activities. All of this dedication and hard work has begun to pay off. Last

year, the Chesapeake Bay Report Card announced that management interventions have

led to the “largest resurgence of underwater grasses ever recorded anywhere”.

Despite this significant success in protecting

and restoring Bay grasses, there is still a persistent need for more widespread

SAV data collection. The aerial survey provides useful information on the

location and density of SAV beds throughout the Bay, but it does not provide

local-scale data on SAV species diversity or habitat conditions. Scientists

have asked volunteers for help collecting these types of data, which could

inform new, targeted restoration efforts and management decisions. Volunteer

SAV monitoring efforts thus far have been relatively irregular, informal, and

uncommon in the Bay; however, growing public interest in SAV, as well as the

successful completion of a volunteer monitoring pilot project, both offer an

opportunity to establish a standardized monitoring protocol and formalized

certification program.

To develop the Chesapeake Bay SAV Watchers program, we began by collaborating with members of a standing workgroup of Chesapeake SAV experts, Riverkeepers, and other professionals in the SAV community to first identify what types of data are most desirable and useful from a science or management point of view, and then reach a consensus on the data parameters and collection methodologies that volunteers should use when monitoring. We also surveyed the leaders of volunteer monitoring groups to collect feedback on the SAV monitoring pilot project last year and invited them to express any needs or concerns for the new program. Finally, we went out in the field with volunteers on several occasions, which was an awesome opportunity for us to learn more about SAV species identification, in general, and more importantly, about volunteers’ monitoring experiences.

We

synthesized all of this information to generate a monitoring protocol, and then hosted a workshop at

the Chesapeake Bay

Environmental Center last

August to field-test the protocol and get face-to-face, in-the-field feedback. Many

Riverkeepers and volunteers joined us to test the

protocol and comment on several aspects of the monitoring program. We also

presented the monitoring program at the 2018 Maryland

Water Monitoring Conference, during a session on citizen science

and SAV in the Bay, and we invited conference attendees to give us feedback

after our presentation. Finally, we consulted with several specialists to

clarify questions about specific data parameters in the protocol and various other

aspects of the project. Finalizing the monitoring protocol and program was an

iterative and collaborative process, and it was both exciting and challenging

to integrate all of the feedback we received throughout the course of the

project.

Our final monitoring protocol is two tiers, which are aimed at two user groups and represent two levels of monitoring intensity. The first tier is designed for people who want to contribute observations of SAV species, but do not necessarily belong to an organized volunteer monitoring group. Participants in the Introductory Monitoring Program use the Water Reporter mobile app or website to create a user profile, join the Chesapeake Bay SAV Watchers group, and upload SAV species observations. For each observation, volunteers identify the SAV species present at their monitoring location, provide a photo of the grasses, and also share other information such as the GPS coordinates of the site. Observations appear on the group page, where members can comment on posts to confirm identifications, ask clarifying questions, or share other information. Scientists can use the shared data to get a better idea of which species are growing in different areas of the Bay.

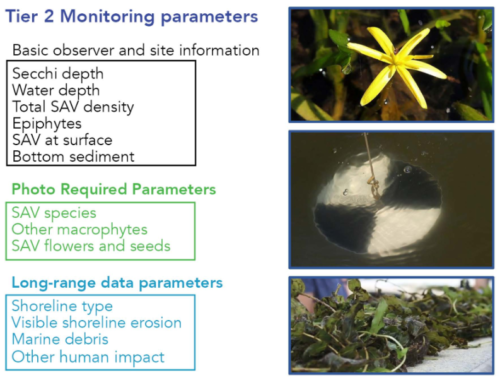

The

tier 2 protocol is significantly more complex, and is designed for citizen

scientists who monitor as members of organized monitoring groups. Participants

in the Advanced Monitoring Program monitor a wide variety of parameters related

to SAV growth, diversity, and habitat. For example, volunteers collect data on

the SAV itself, such as species diversity, density, and reproductive

structures, but also record observations that describe the surrounding area,

including water clarity, the type of shoreline or sediment, and the presence or

absence of other plants like water

chestnut. They record their observations on printed datasheets, which

are then digitized and shared with scientists, for incorporation into the interactive map of SAV in the Chesapeake Bay.

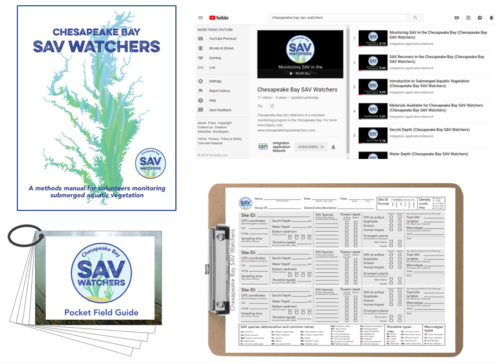

In addition to the monitoring protocols, we developed a methods manual with many resources on SAV and monitoring, such as background information on SAV, guides for how to select sampling sites and take high-quality photos, and an SAV species key. We also created a datasheet, a series of training videos, and a pocket-sized field guide for volunteers to use in the field. Finally, we created an agenda for a two-day training and certification course for volunteer coordinators. The course will teach volunteer coordinators how to identify SAV species, properly collect monitoring data according to the Chesapeake Bay SAV Watchers protocol, and then go on to train members of their own volunteer groups to participate in the program.

The resulting collaboratively-developed protocol and training program reflects the interests of the broader Chesapeake SAV community and hopefully empowers volunteers to engage with their environment and with each other in order to support research and protection of Bay grasses. This summer will be the first sampling season where the Chesapeake Bay SAV Watchers program is introduced. Developing this program was a very rewarding experience, and I am eager to see this program continue to grow and improve over time.

About the author

Suzanne Webster

Suzi Webster is a PhD Candidate at UMCES. Suzi's dissertation research investigates stakeholder perspectives on how citizen science can contribute to scientific research that informs collaborative and innovative environmental management decisions. Her work provides evidence-based recommendations for expanded public engagement in environmental science and management in the Chesapeake Bay and beyond. Suzi is currently a Knauss Marine Policy Fellow, and she works in NOAA’s Technology Partnerships Office as their first Stakeholder Engagement and Communications Specialist.

Previously, Suzi worked as a Graduate Assistant at IAN for six years. During her time at IAN, she contributed to various communications products, led an effort to create a citizen science monitoring program, and assisted in developing and teaching a variety of graduate- and professional-level courses relating to environmental management, science communication, and interdisciplinary environmental research. Before joining IAN, Suzi worked as a research assistant at the Marine Biological Laboratory in Woods Hole, MA and received a B.S. in Biology and Anthropology from the University of Notre Dame.