Do’s and Don’ts: How scientists and the law can exist in tandem

Fan Zhang, Emily Russ, Whitney Hoot · | Science Communication | Applying Science | 4 commentsFan Zhang, Emily Russ, Whitney Hoot

When we talk about scientists, we envision someone wearing a lab coat and exploring nature’s mysteries, a professor passing knowledge to the next generation or a group of people who enjoy debating and discussing abstruse topics. We know that these are important professional activities for scientists, in academia and beyond. But sometimes scientists have more challenging jobs: dealing with the law, and it can be a nightmare if it goes wrong.

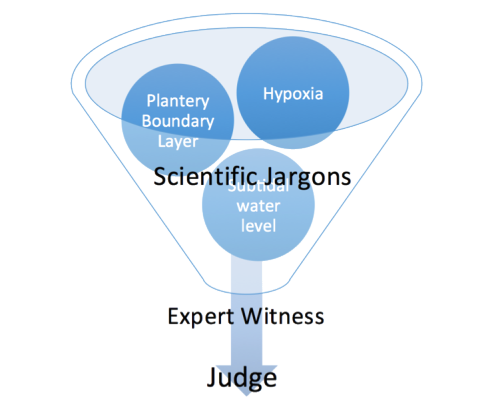

Integrating these disciplines can be challenging. In fact, there could be very deep water between these two distinct regions. Scientists need to build the bridge and translate scientific jargons into understandable concepts for a judge or the public. For instance, uncertainty is commonplace in science, but this statistical concept can be completely misinterpreted by non-scientists. People may not understand why in recent decades it is so frequent to see “one-in-one-thousand year” storms unless they are told clearly by the scientists that “one-in-one-thousand year” does not really mean such a storm happens only once in one thousand year and actually it is a statistical concept.

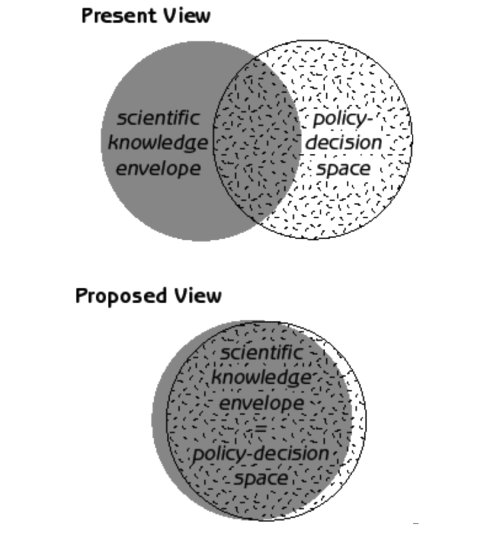

Therefore, scientists need to assume specific roles in the legal process in order to help translate their data into policy. Scientists may be part of an agency and work on litigation processes such as the establishment of Chesapeake Bay total maximum daily loads (TMDL). These agency scientists are tasked with developing expert reports, which serve as the basis of most administrative agency decisions. However, even though science is very important in this process, a minority of statutes say that all you need to look at is science; most statutes are developed by balancing science, economics, and political factors. Although scientists are careful about the data they collect and strive to construct robust models, a clear explanation of these models and data to the public is necessary to reduce the chance of criticism and controversies, like those associated with the Chesapeake Bay TMDL (Andrew Jenner, 2011).

Scientists can also serve as expert witnesses in the legal process, who by virtue of education, are believed to have expertise and specialized knowledge in a particular subject beyond that of the average person, sufficient that others may officially and legally rely upon their scientific opinion about a fact within the scope of his or her expertise, referred to as the expert opinion, as an assistance to the fact finder (Federal Rules of Evidence, 2011). For example, Dr. Don Boesch, a famous oceanographer, used his knowledge to defend for the government in the Deep Water Horizon oil spill case.

Although scientists can work very closely with developing environmental laws, they can be very vulnerable. Here are some tips to help scientists avoid traps and serve as valuable asset in the legal realm:

For an agency scientist:

- Always ask yourself how robust the science is and whether we can rely on it to inform sound policies.

- Agencies are fallible and sometimes we need outside consultants to pick up on other details. Private science delivered through consulting firms can help lead to enforcement.

- Be aware that the press and the public can get science wrong and we need to better explain our policies to the public and build trusting relationships. For example, the public tends to think the rain tax is on the rain, which has nothing to do with them; however, the tax is about the nutrients the rain carries into the bay. Better communication could reduce the chance of miscommunication, misunderstanding, and distrust.

- Expect some lawsuits and have some legal perspective for the situation such as American Farm Bureau Federation (AFBF) and the Pennsylvania Farm Bureau (PFB) filed suit in federal court to block the TMDL set for the Chesapeake Bay.

For expert witnesses:

- You are only an expert as much as the judge thinks you are.

- Never talk “too much”. Too much talking can increase the chance of misspeak, especially if you are not very familiar with the legal process, which could be taken advantage of by the lawyer.

- Know what the judge wants from you and prepare your testimony so it fits the case.

- Be aware that the terminology about uncertainty in science has a fundamentally different meaning from what the public understands.

- Stay true to the data.

- Make sure there is a scientific basis for the point you are going to make; avoid arbitrary and capricious conclusions.

- Lawyers may have nothing to attack you on the basis of science, so they reach into your past. Think about how to defend that part.

- Minimize sending emails, texts or anything could leave a paper trail. Talk on the phone when discussing anything that may be sensitive.

- Understand you are in a different forum for communicating things and be as definitive as you can.

- Understand the legal process, since the game is played differently than scientific/peer review process.

- Use repeatable scientific studies to help you establish credibility as an expert witness.

References:

- Andrew Jenner, 2011. Farmers, EPA clash over Chesapeake Bay regulations.

- Federal Rules of Evidence – 2015. Federal Evidence Review.

- Bradshaw, Gay A., and Jeffrey G. Borchers. "Uncertainty as information: narrowing the science-policy gap." Conservation ecology 4.1 (2000): 7.

Next Post > In memory of Jay Zieman, University of Virginia seagrass ecologist

Comments

-

Suzanne Spitzer 11 years ago

Scientists should also remember that court trials and policy-making decisions that concern the environment often incorporate a cost-benefit analysis of different stakeholder interests. Policymakers and judges should ideally consider the effect that potential laws and judicial decisions might have on the environment, as well as on the economy, human health, and various sociocultural factors. Balancing the diverse interests of various stakeholders is an integral part of best scientific management practice and should carry over to the courtroom. As scientists, we must remember that our role in the legal cycle is to provide accurate and timely information while avoiding the danger of being seen as simply an emotional advocate. Doing this successfully, using the guidelines suggested by the authors of the blog post, will help to assure that environmental and biological concerns are properly considered when making judicial or legislative decisions.

-

Sabrina Klick 11 years ago

The article does a very good job in giving advice for professionals in science fields and how to communicate as a witness. There were a few places that were unclear/confusing to me. For example, I am not sure what was meant by the sentence: "In fact, there could be very deep water between these two distinct regions". Overall, the author did a great job on the diagrams and it was very creative to have the bullet points at the end for tips/advice. The bullet points will be easy an easy guide if somebody needs quick advice later on.

-

Adriane Michaelis 11 years ago

This article serves as a great summary of the tips/advice discussed in class regarding science and the law. One of the overarching themes in this piece, and throughout the majority of our course this semester, is the importance of effective science communication. Regardless of how much knowledge a scientist has in a subject area, it does no good if they are unable to convey it effectively. This holds true in many realms, including the courtroom.

-

Wenfei Ni 11 years ago

There is no witness for environmental violation and damage. What scientists could do is to provide the study result based on current researches, as a special 'evidence' and basis for legal judgment. There are certain deflects and restrictions on the study which scientists know clearly. However, the "worst" is always better than nothing. So following the tips mentioned in the article on how to face the public and judge becomes important.

Noticing the relative integrities of science and legislation, the agency emerges, to which the primary goal is not scientific priority, but rather the specific case. It focuses on data and historic records, working for a reasonable result. And scientific experts need to stand out, making sure these results keep on reliable scientific track and communicating with judge meanwhile. This need scientist being at the right position at the joint zone.