Engaging with the Belyuen people and Larrakia people, Traditional Owners of Darwin Harbour, Australia

Bill Dennison ·

Simon Costanzo and I travelled to Darwin to initiate a comprehensive Darwin Harbour report card. For the past decade, Julia Fortune, Northern Territory Department of Environment and Natural Resources, and her colleagues have been producing a regular and rigorous water quality report card for the extensive waters of Darwin Harbour. But the Darwin Harbour Advisory Committee has recognized the need for a more comprehensive report card to include social, indigenous, cultural, economic and environmental aspects. So we collaborated with Dr. Karen Gibb, Charles Darwin University, to obtain funding support from the Ian Potter Foundation with matching funds from several sources.

Simon worked with Larraine Williams, a Larrakia woman, to arrange a visit with about 15 Belyuen people to initiate a conversation about their values regarding Darwin Harbour. The original workshop was scheduled at a community hall in Belyuen with 30+ people. Even though there were no reported cases of COVID-19 in the Northern Territory, we relocated the workshop to an outdoor venue and reduced the number of attendees to avoid possible spread of infection. The venue actually proved to be very authentic and enjoyable.

We started off the workshop with introductions and an explanation of what we were doing. One of the key questions they asked us was "Why are you doing this?" Our response was that we have been developing report cards around the world and that by including indigenous culture along with social, economic and environmental values, we had the opportunity to develop a more comprehensive report card than elsewhere. In addition, it was our experience as scientists developing report cards that we found them to be the single most effective way that we could induce behavior change. They were assured that we did not represent government or industry and we were serving a neutral facilitators rather than proponents for developers or environmentalists.

We invited the workshop attendees to provide a list of their top values regarding Darwin Harbour. We recorded this list on a large piece of butcher paper and posted the list on the basketball court fence. Attendees were given sticky dots to vote on the priority list. A clear pattern emerged in terms of priorities: 1) clean water, 2) preserving the Harbour for future generations and 3) protecting various sacred sites. At first we were confused as to why healthy habitats and animals did not make the list even though we had a lot of discussion about mangroves, seagrasses, rocky reefs, and mud flats as well as fish, shellfish, turtles and dugong. But on reflection, focusing on clean water as the underlying basis that supports healthy habitats and healthy sealife was appropriate. And then linking clean water to preserving Darwin Harbour for future generations and protecting indigenous sacred sites embedded the healthy habitats and sea life firmly within an integrated cycle.

We then turned our attention to a discussion of indicators for these priority values. Creating effective two-way communication between Belyuen and Larrakia people and the various other Darwin Harbour stakeholders was seen as a priority. The Aboriginal people are often the first to observe some of the changes in the Harbour as a result of their close association with the land and water. Many of the proposed developments in the Darwin region affect Larrakia and Belyuen people and they need to be informed and consulted on these issues.

Another key indicator was respect for country. The Belyuen people were concerned about rubbish and litter—I noticed that the recreational area where we held the workshop as well as the surrounding housing was spotlessly clean. They brought up the issue of off road vehicles and the disrespect for their sacred sites that sometimes occurs.

The issue of indigenous cultural knowledge, both men and women's knowledge, was important. They identified a need for funding support to ensure cultural knowledge was passed on to the next generations of indigenous people. They stressed the importance of indigenous language, song, dance, story, ceremony and country.

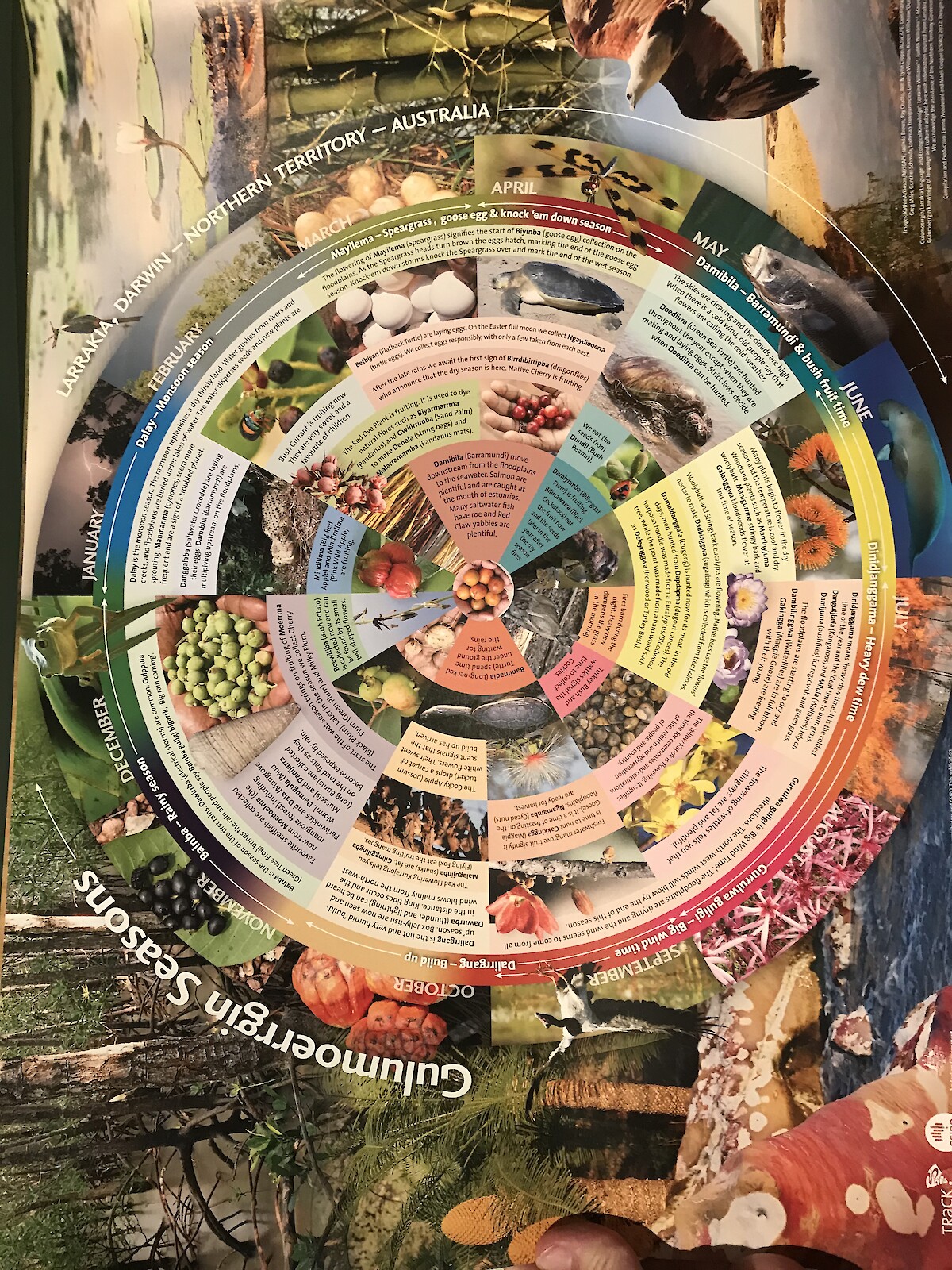

The impacts of climate change were a topic that they raised throughout our conversation. The Larrakia people have produced a wonderful seasonal calendar, depicting seven seasons in an annual cycle; a) rainy season, b) monsoon season, c) goose egg & knock 'em down season, d) barramundi & bush fruit season, e) heavy dew time, f) big wind time and g) build up season. The Belyuen people have created a similar calendar. They indicated that the seasons were shifting in terms of start/end dates as well as relative lengths. They raised the topic of the potential to have members of the Belyuen and Larrakia communities make observations and record data on these seasonal changes they were observing (e.g., citizen science).

In order for us to generate data regarding the values and indicators nominated in the workshop, we discussed developing a survey that would be administered through oral questionnaires to indigenous people. We also were encouraged to maintain our engagement with them throughout the development of the report card, something we readily agreed to.

The workshop included several small children that would alternatively run around and then rest in the laps of the adults. There were more women than men at the workshop and the women were more conversant, often encouraging the men to join in.

In conversations with Karen Gibb, we had decided to produce a short (ca. 3 minutes) video to describe the process of developing a comprehensive Darwin Harbour report card. Karen introduced us to a photographer/videographer, Nicholas Gouldhurst, Black Feather Productions. Nicholas turned out to be a great collaborator and we brought him to Belyuen with us. He filmed us conducting the workshop and after the workshop was over, we traveled to the mouth of a mangrove-lined creek that flowed into Darwin Harbour so that Nicholas could obtain footage of Larrakia people fishing using traditional means. I was impressed at the young Belyuen woman, Rowena who consistently threw perfect circles with a cast net, catching small mullet each cast. Two older women collected periwinkles and whelks among the mangrove roots. The highlight was when Christo, a tall young man, stealthily waded into the creek to spear a large mud crab. Everyone was excited about his successful catch.

I have conducted countless workshops with a wide diversity of stakeholders throughout my career, but this was one of the most memorable and interesting workshops I have experienced. I felt very privileged to have had this magnificent opportunity.

Notes from Lorraine Williams:

Belyuen people live in the Belyuen Community, the are made up of three language groups, Batjamalh, Emmiyangal, Mendheyangal. Their traditional lands are further down south of the west coast, but maintain custodial responsibilities for the area of Belyuen Community on the Cox Peninsula.

The Larrakia people are the Traditional Owners of Darwin and the Cox Peninsula, however only 6 people were given Traditional Ownership status to the Cox Peninsula. The Kenbi Land Agreement was finalised and the land handed back in 2017. There is currently a High Court challenge and decision pending in regards to the hand back, by the Larrakia.

About the author

Bill Dennison

Dr. Bill Dennison is a Professor of Marine Science and Vice President for Science Application at the University of Maryland Center for Environmental Science.