Environmental Literacy for the tropical Northern Territory, Australia

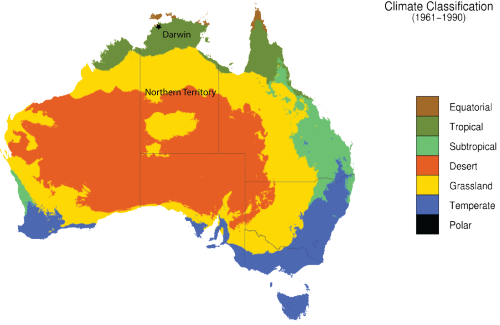

Heath Kelsey ·As part of our ongoing project with Charles Darwin University to synthesize the research on the flood plains of Kakadu National Park, we review the fundamentals of the environment and characteristics of the region, specifically the coastal tropical areas in the northern part of the territory. The Northern Territory is the third largest state or territory in the country with about 17.5% (1.3 million km2) of the land area. Despite its large size, the Territory has only about 1% (about 210,000 people) of the population, which makes it the most sparsely populated area in the country. The northernmost ¼ of the territory or so has a wet/dry tropical climate; areas to the south are much more arid. We focus our discussion mostly on the northern, tropical regions of the state.

1. Climate and temperature

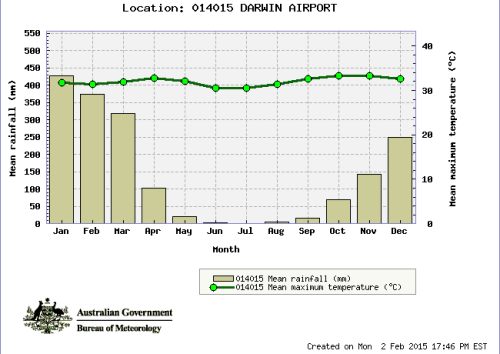

Generally, the coastal areas of the Northern Territory are hot and humid almost always, with two seasonal variations: the Wet Season (November-April) and the Dry Season (May-October). Annual variations are common in the start of the seasons and in the intensity of the annual rainfall. There are subtle seasonal variations also; for example the end of the dry season is often called the “Build Up,” referring to the building humidity in September and October, before the relief that comes with the rains. Highest temperatures occur in November and December with a mean high of 33.2C. Mean high temperature only varies by 2-3C, but low temperature varies a bit more. Highest rainfall occurs in January, with a mean rainfall of 426mm.

2. Aboriginal cultures and resources

Approximately 30,000 aboriginal people live in the northern areas (Northern Land Council jurisdiction) of the Northern Territory, scattered among 200 communities and large towns in seven regions. The Northern Land Council was established following the passage of the Aboriginal Land Rights Act in 1976 to represent the interests of aboriginal people in the northern regions of the Northern Territory. Since then ownership of about 50% of the land mass and 85% of the coastline in the territory has been returned to aboriginal peoples in the Northern Land Council area.

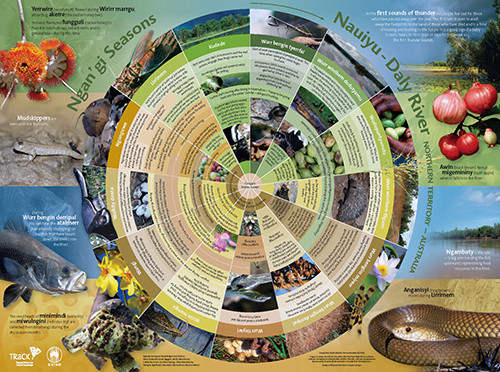

As aboriginal people have been living on the land for upwards of 50,000 years, they also possess a keen understanding of natural cycles. Aboriginal seasons can include far more intricate descriptions depending on location, and seem to be based on resource abundance and observation of natural shifts. The southern, more arid portions of the Northern Territory have subtle seasonal variations compared to the northern, tropical areas, and the aboriginal calendars reflect that.

3. Threatened wildlife

Compared to many other communities worldwide, the landscapes of the Northern Territory are relatively unimpacted by development. However, there are over 200 species of plants and animals considered threatened in the NT, including 22 species of small land mammals, which have rapidly declining populations, and marine mammals, which have largely unknown ecologies. Threats to land animals include introduced species, like water buffalo, cane toads, and weeds, and changes in fire regimes. Strategies to conserve or protect these species include work done through the National Environment Research Programme, and Territory Natural Resource Management.

![NERP funded conservation strategy document for threatened species in Kakadu National Park [pdf]. Credit: http://www.nerpnorthern.edu.au NERP funded conservation strategy document for threatened species in Kakadu National Park.](/site/assets/files/2425/4-threatened-species-500x707.jpg)

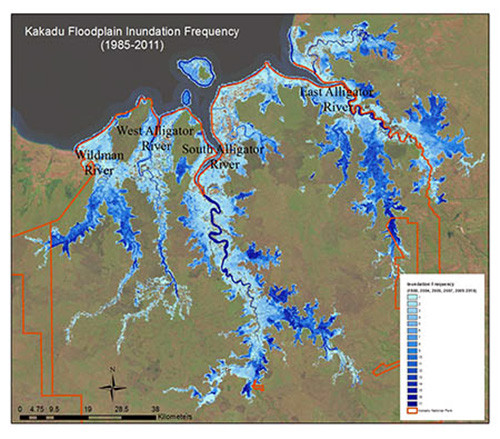

4. Rivers and Flood Plain Importance

The major geographic feature of the coastal areas of the Northern territory are the rivers and their flood plains. During the wet season, vast flood plains are inundated with freshwater overflowing the dry season riverbanks, reconnecting the river and the energy and nutrients in the flood plains, and providing essential habitat for crocodiles, geese, turtles, birds, and fish. These connections are vital for ecosystem function, which supports coastal fisheries, tourism, and inland recreational fisheries. Barramundi in particular is an important species for recreational and cultural fishing in northern Australia. Sawfish is also an important species, as it is an endangered species found only in the region.

5. Crocodiles

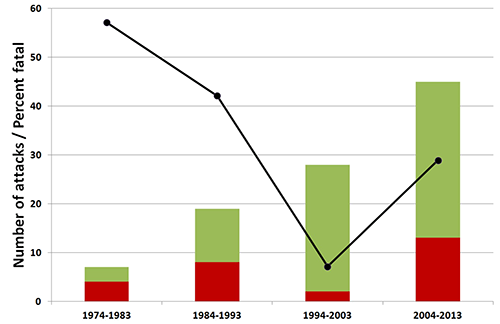

Crocodiles are an important attraction and resource here, emblematic of the wild and slightly dangerous reputation established for the “Top End” of Australia. Saltwater crocodiles are genuinely dangerous, and according to Adam Britton and Andrew Campbell at CDU, account for 2.3 attacks per year on average from 1999 to 2013, about 27% of which were fatal. The authors point out that the number of attacks is low compared to other countries, despite Australia having the highest density of saltwater crocodiles in the world, and lots of tourists and outdoor enthusiasts. They credit a well-executed crocodile management program.

Litchfield National Park, about 2 hours from Darwin, has some of the most spectacular scenery you’ll find anywhere, and lots of crocodiles, especially in the wet season. Warning signs are common, and are a key part of the plan to reduce crocodile attacks. Although called “saltwater crocs,” they are equally at home in fresh, estuarine, and marine waters, and make their way far inland during the wet season. Similarly, freshwater crocodiles can tolerate saltwater, but are much less aggressive and smaller than their saltwater cousins.

6. Weeds and Fire

Gamba grass, para grass and Olive hymenachne are invasive weeds that reduce biodiversity and habitat on the floodplain, increase fire damage, and potentially change carbon stocks. Fire has been used as a management tool well before European settlement, but weeds such as Gamba grass increase the fuel load and temperature of fires, which destroy resources resilient to previous fire regimes. These grasses are spreading throughout the Northern Territory and are pressuring resources to control them. Kakadu National Park floodplains are particularly vulnerable to spread of para grass and O. hymenachne, by reducing biodiversity of habitat for key species important as food sources or “bush tucker” for aboriginal communities. The park invests substantial resources to manage and control the spread of invasive grasses.

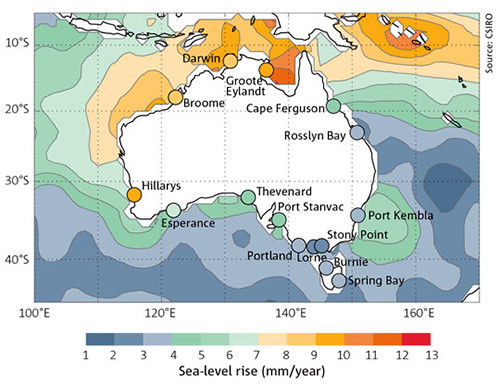

7. Sea Level Rise

According to the Commonwealth Scientific and Industrial Research Organisation (CSIRO), sea levels in Darwin have risen more than 17mm since 1994, which is 2-3 times the global average, and the consequences are already being observed. Sea Level Rise will threaten infrastructure and alter salinity regimes in coastal floodplains, which will subsequently alter species composition, biodiversity, and habitat.

About the author

Heath Kelsey

Heath Kelsey has been with IAN since 2009, as a Science Integrator, Program Manager, and as Director since 2019. His work focuses on helping communities become more engaged in socio-environmental decision making. He has over 10-years of experience in stakeholder engagement, environmental and public health assessment, indicator development, and science communication. He has led numerous ecosystem health and socio-environmental health report card projects globally, in Australia, India, the South Pacific, Africa, and throughout the US. Dr. Kelsey received his MSPH (2000) and PhD (2006) from The University of South Carolina Arnold School of Public Health. He is a graduate of St Mary’s College of Maryland (1988). He was also a Peace Corps Volunteer in Papua New Guinea from 1995-1998.