Exploring Hawaii: arid zone ecology, vog and volcanoes

Bill Dennison · | Applying Science | 1 commentsDave Helweg and Christian Giardina organized a field trip on the Big Island of Hawai'i immediately following our workshop on Oahu. When the plane that Simon Costanzo and I were on landed in Hilo, Christian contacted us to inform me that his wife, Ingrid Dockersmith, had sailed with me aboard the R/V Westward as part of Sea Semester. I was the Chief Scientist and Ingrid was an Assistant Scientist when we left from Maine and sailed to Barbados, Bequia and eventually St. Thomas after six weeks at sea. We visited with Christian and Ingrid and caught up on sailing stories. Ingrid filled me in on the lush garden she maintained which produced various tropical fruits; an illustration of the vegetation supported by the more rainy windward side.

The following morning, we met at the Institute of Pacific Islands Forestry, Christian's worksite, a facility operated by the US Forest Service. Our field trip crew included Dave Helweg, Christian Giardina, Shawn Carter, Simon Costanzo, Abby Frazier, and Ashlie Denton (from Portland State University). We headed west over the Daniel K. Inouye Highway (aka Saddle Road) that connects the windward (wet) side of the island with the leeward (dry) side.

Our first stop was at the Pohakuloa Training Area, a 133,000 acre installation operated by the US Department of Defense. Christian and his colleagues have been able to establish various experimental plots within the training area to study restoration ecology. At this site, Christian introduced us to a non-native ornamental grass which is a major pest species on Hawai'i: Fountaingrass (Pennisetum setaceum). Fountaingrass develops thick carpets, which become dried out during drought and eventually develop into a fire hazard. We also were introduced to a native plant that produced a distinctive odor of fish when the leaves were crushed. This plant was named 'Aweoweo' (Chenopodium oahuense), which is also the name of a native Hawaiian fish (Priacanthus sp.). We also learned about the native shrub A'ali'i (Dodonaea eriocarpa), in which they have had some success in restoration programs.

Next, we visited the Pu'u Wa'awa'a Conservation Area, which Elliott Parsons had introduced at the workshop. Edith Adkins, Project Planner with the Hawaii Department of Forestry and Wildlife (DOFAW), met us at the site and showed us some of the conservation plantings and talked about some of the community group conservation efforts. Edith showed us the resident nēnē geese (Branta sandvicensis), the iconic Hawaiian bird which is the rarest goose on the planet. When Captain Cook arrived in the 'Sandwich Islands' in 1778, there were an estimated 25,000 birds. Now there are only 2,500 birds, which were restored from a founder stock of 12 birds that had been stewarded overseas. Edith's team attempts to preserve some very endangered plant species, including some species with their total population size less than a dozen plants.

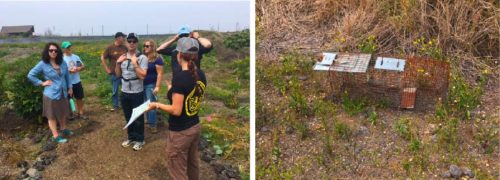

One of the overriding themes of our day in the dry shrublands of Hawai'i was the presence of so many exotic plants. We saw three kinds of trees common in Australia, the silky oak (Grevillea robusta), Eucalyptus trees and Jacaranda trees (also introduced from South Africa). But we also saw native species, including the Hawaiian state flower, Ma'o hau hele (Hibiscus brackenridgei), and unique endemic trees Kauila (Alphitonia ponderosa) and Wiliwili (Erythrina sandwicensis). We saw traps set to catch non-native mongoose, and we saw and heard feral goats, and saw bones from cattle, serving to emphasize the role of exotic animals on Hawaii's ecology.

After a nice lunch break at a small state park along a beach, we went to the Pu'ukohola Heiau National Historic Site, where Ben Saluda, interpreter for National Park Service, told us the story of the wildfire that passed through the park and led to severe erosion after subsequent rains. We could see tree trunks in the nearshore waters near the stream mouth which resulted from this erosion event. This was a vivid illustration of the impact of ecodrought on not just the landscape, but also the adjacent seascape.

We were joined by Natalie Kurashima, of Kamehameha Schools, who studied the ethnobotany and native Hawaiian agriculture in this area of Hawai'i Island as we walked around the site of King Kamehameha's temple on the side of Whale Hill (fittingly, we spotted whales in the ocean). We saw a native catamaran reconstruction on the beach. We were not able to see neighboring islands due to the presence of 'vog', a term for reduced air quality due to active volcanism. We said our goodbyes to the larger group, and Simon, Abby, Ashlie and I continued on to make a short visit to the Kaloko-Honokohau National Historical Park to see the reconstructed native Hawaiian fish ponds. This park is also known for its rare anchialine pools, which are small brackish water ecosystems in the lava rock near the shore which are fed by freshwater via groundwater infiltration and by seawater that seeps through the lava.

After this field trip through the arid section of Hawaii, the four of us felt compelled to rehydrate ourselves at a veranda pub overlooking dragon boats plying the waters of the Kona inner harbor. We then dropped Ashlie at the Kona airport and drove around the southern coast road toward Hilo. We passed South Point, the most southern point in the United States, and made our way to Volcanoes National Park. We could see the red glow as we neared the active lava lake in the Kilauea caldera. We were treated to an active, noisy show, as the lava was tossed up onto the air, and lava waves sloshed against the sides of the lake. We decided that it was better than fireworks. It also was a great way to end the day exploring the natural beauty of Hawai'i.

About the author

Bill Dennison

Dr. Bill Dennison is a Professor of Marine Science and Vice President for Science Application at the University of Maryland Center for Environmental Science.

Next Post > Moana Revisited

Comments

-

Sydney 9 years ago

Thank you for sharing about your experience on the Big Island. It's nice to hear about the preservation of plants and animals. I'm glad you were able to appreciate many of the wonderful sites of the island.