Exploring New York Harbor: Walking across the Brooklyn Bridge

Bill Dennison · | Learning Science |As part of our involvement in the New York Harbor. I read "The Great Bridge: The epic story of the building of the Brooklyn Bridge" by David McCollough. It was a wonderful read, providing historical context and delving into the fascinating story of the three Roeblings who were key to the effort: John Roebling, a Prussian immigrant and engineer; Washington Roebling, John's son, a civil war hero and engineer, and Emily Warren Roebling, Washington's wife who serves as an informal general contractor after John died and Washington was crippled.

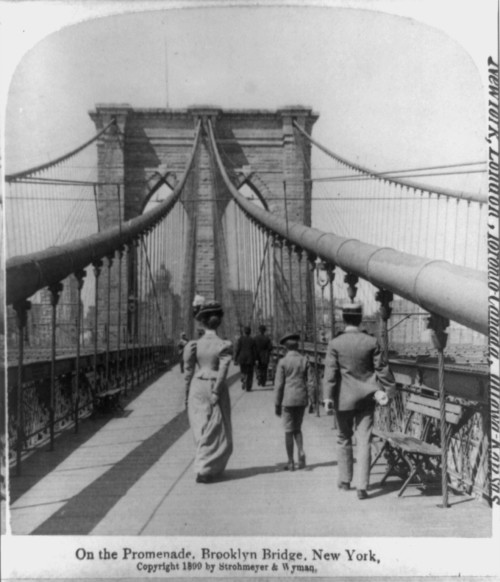

We picked a sunny, but cold day to walk over Brooklyn Bridge, walking from the Brooklyn side to Manhattan between Christmas and New Years. I couldn't believe how crowded the promenade was with people taking photos and enjoying the view. I reflected on what an incredible legacy the Roeblings provided to New York City. This beautiful yet functional structure has been serving as a major transportation corridor across the East River every day for over 130 years, and is still a major tourist destination, based on the number of different languages I overheard on the bridge.

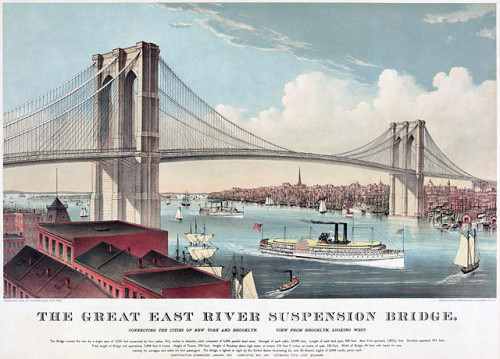

The two massive towers that were built to support the four suspension wires of the Brooklyn Bridge were the most massive structures built in North America, and only the spire of Trinity Church in lower Manhattan was taller at the time. The pedestrian promenade is suspended above the roadway between the suspension cables and there is a viewing deck at each of the towers. The bridge construction occurred between 1870 and 1883, following the American Civil War, linking what were two separate cities, New York and Brooklyn. The three Roeblings had important roles in the bridge construction.

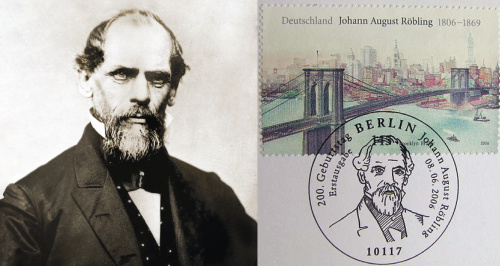

John Roebling (1806-1869) was a Prussian immigrant who arrived in America to start up a company that manufactured steel wire--the material used in suspension bridges. The Brooklyn Bridge was not the first suspension bridge constructed by John Roebling--he had built bridges spanning the Monongahela River in Pittsburgh and the Ohio River in Cincinnati. However, these bridges did not require the use of caissons (large, pressurized underwater compartments) for the construction of the supporting towers and the spans were much shorter than the Brooklyn Bridge. John Roebling was a very authoritarian figure, and an incredibly hard worker. He settled in Trenton, New Jersey and had been promoting the concept of an 'East River Bridge' for an extended period. Tragically, John Roebling was the first casualty of the construction of the bridge after his foot was crushed by a ferry while surveying the Brooklyn riverfront. Roebling was a believer in 'hydrotherapy' and ran cold water over his injured foot, which did not protect him from the tetanus infection which set in and led to his death by 'lockjaw'.

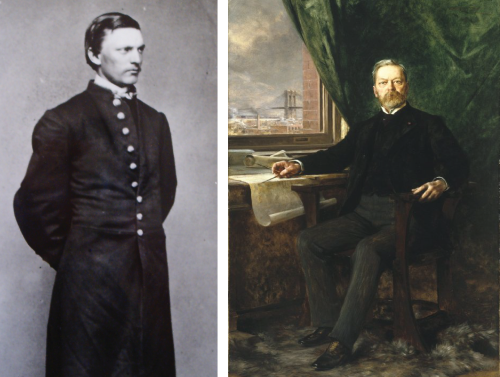

Washington Roebling (1837-1926) was John's eldest son who inherited both the wire business as well as the job of constructing the Brooklyn Bridge. Colonel Washington Roebling served in the Union Army during the American Civil War and was present at several major battles including Manassas II, Antietam and Gettysburg. He served as an aide to General Gouverneur Warren and was the first man to mount Little Round Top, spotting Confederate troop movement and warning the Union Army, prior to one of the most decisive battles of the Civil War. During the war, Washington Roebling met General Warren's sister Emily, and they carried on a correspondence which resulted in marriage in January 1865. Washington Roebling's unique contribution to the bridge construction was his understanding of the caissons used to form the bridge tower foundation, which he learned by his acute power of perception during a trip to Europe.

Emily Warren Roebling (1843-1903) was Washington's wife who had no formal training in engineering, yet became proficient in directing the bridge construction as a messenger from her ailing husband, Washington. The Roeblings lived in Brooklyn Heights and could watch the construction of the bridge from their house. Emily went to the bridge regularly, sometimes making two or three trips a day. When a manufacturer had some questions about the bridge, he visited the Roebling house and was impressed at her knowledge level displayed when she used drawings and made detailed explanations.

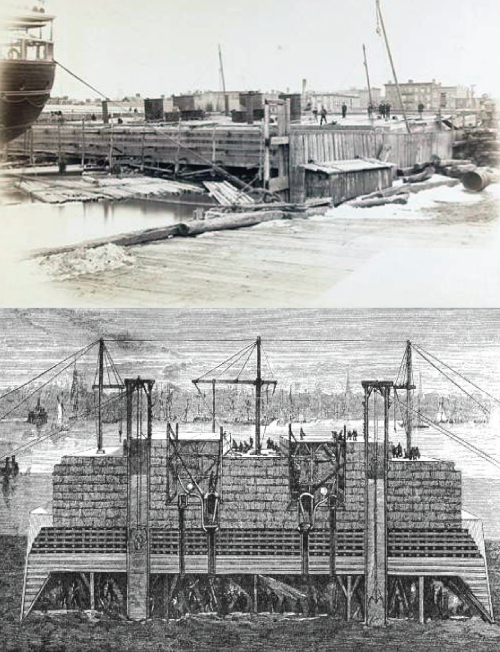

Washington Roebling was crippled from the “bends”, now known as “decompression sickness” and initially called “caisson’s disease”. This malady arises from the rapid dissolution of nitrogen gas in the blood following decompression. Washington Roebling directed a fire fighting operation that occurred inside one of the timber caissons and spent too much time at pressure without a proper decompression period and suffered for the rest of his life. The caissons were a key engineering aspect of the construction. They were massive wooden boxes sheathed with iron that were weighed down with rockwork and were positioned over the bottom of the East River. Compressed air was fed into the caisson to prevent flooding and immigrant workers dug into the river bed and removed rocks by hand. The Brooklyn caisson was 44 deep when bedrock was encountered and the New York caisson was 78 deep when digging stopped in a sand layer. Both caissons were filled with concrete and serve as the base of the towers.

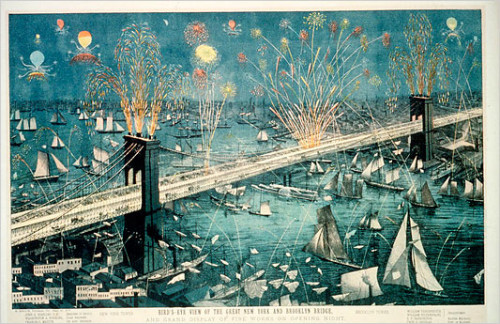

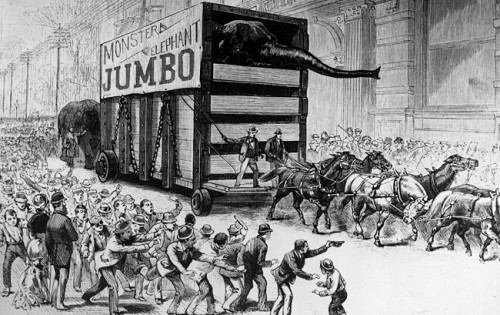

Building the bridge was dangerous and nearly 30 people perished during the construction. William “Boss” Tweed, a corrupt New York City politician, was involved in the early phase of bridge construction, mostly to obtain lucrative contracts for his associates. Opening day (May 24, 1883) for the Brooklyn Bridge was quite an event, with President Chester Arthur, New York Governor and future President Grover Cleveland leading the ceremonial march which included Emily Roebling. The President and his entourage made their way to the Roebling house following the ceremonies to pay their respects. The memorable opening day included boats, bands, speeches and an amazing fireworks display. A few days following the opening of the bridge, a stampede of people who mistakenly thought that the bridge was going to collapse led to 12 deaths. The following year, P.T. Barnum organized for 21 elephants to cross the bridge to prove its safety and help ally people’s fears.

The daily bridge traffic is impressive. Historic traffic counts when the elevated trains (until 1944) and streetcars (until 1950) were in use had 341,000 people crossing each day (up to 426,000 in 1907). With the advent of the automobile and more bridges and tunnels in New York, less people cross daily, but current traffic is still an impressive 120,000 automobiles, 4,000 pedestrians and 3,100 bicycles daily. Those are impressive numbers especially considering the 130+ years of continuous use.

The Brooklyn Bridge promenade deck is still unique and based on my recent crossing has remained a New York icon. The Roeblings would have been happy to see the product of their incredible efforts so much appreciated long after this bridge was constructed.

About the author

Bill Dennison

Dr. Bill Dennison is a Professor of Marine Science and Vice President for Science Application at the University of Maryland Center for Environmental Science.