Greater than the sum of its parts: What is a coupled human and natural system?

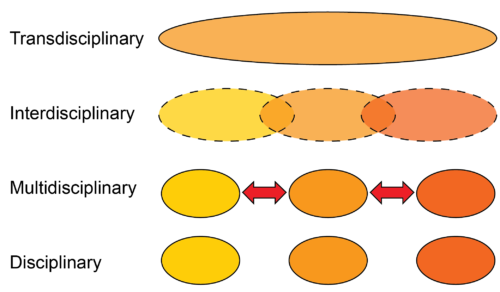

Suzanne Webster · | Science Communication | Applying Science | Learning Science | 12 commentsThis semester, we will be publishing a series of synthesis blogs written by graduate students enrolled in a new course called “Coupled Human and Natural Systems.” The class is the foundation-level course of Environment and Society, a new academic track within the MEES graduate program at UMCES. The MEES curriculum was recently redesigned with the intent of providing “a balance of disciplinary strength and interdisciplinary perspective.” This class will address that goal by encouraging students to collaborate with people outside our fields of study, integrate others’ knowledge and perspective into our research, and aspire to conduct our own transdisciplinary research.

We began our class discussion this week with a seemingly simple question: What is a coupled human and natural system? A Google image search of this phrase yields hundreds of different diagrams; clearly, defining this concept is not an easy task, and the answer varies depending on who is asked. In fact, the four professors of this team-taught class each shared a different way of conceptualizing a coupled system, from their points of view as researchers in the fields of anthropology, geography, sociology, and marine science. Inspired by many definitions and diagrams, we asked ourselves: If our class could draw a coupled system based on our collective understanding stemming from our class materials, how would our sketch come out?

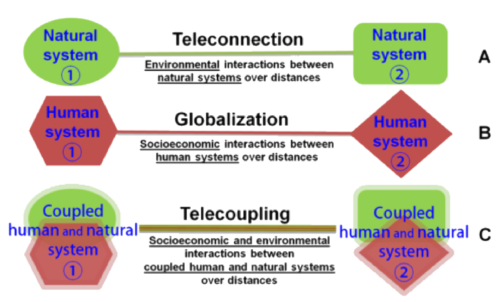

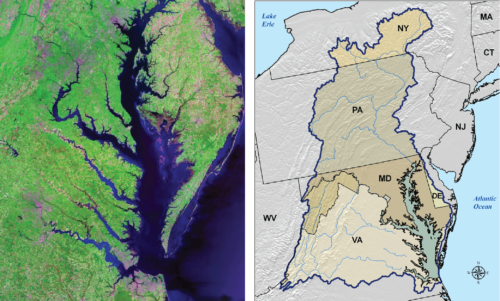

To start, we began by discussing the components of a coupled system. At a basic level, coupled systems are comprised of human and natural components, which share nonlinear interactions, such as feedback loops, thresholds, and time lags, that vary across space and time1,2. A coupled system can also be linked over distances to other coupled systems. Studying these “telecoupled” interactions can help people improve their adaptive capacity by understanding tradeoffs, synergies, and feedbacks that exist between networked systems.

Within a coupled system, there is a social system and a natural one. How do these systems interact? If they are linked, are they integrated into one single all-encompassing socio-ecological system, do they remain separate but overlap slightly, or is one system nested inside the other? Someone asked, “Is it possible for an ecological system to exist without a human system? Can we study social systems without linking them to natural environment?” An immediate difference of opinion amongst my classmates was revealed, as some people nodded and others shook their heads.

We took a step back in our discussion and instead tasked ourselves with trying to identify how human and natural systems are fundamentally different from one another. What followed was an interesting series of suggestions, almost all of which were ultimately accompanied by contradicting examples:

1. Natural systems have defined Laws (laws of thermodynamics and gravity), whereas human systems are more unpredictable.

2. All components of a natural system are fundamental to survival, whereas human systems involve nonessential components like social media and recreation.

3. Natural systems have definable physical limits, whereas boundaries in human systems are more arbitrary (ex: where country lines are drawn, age at which a person is considered an adult, etc.)

4. Natural systems can be studied objectively, whereas the study of human systems is subjective since we ourselves are a part of them, and inevitably impart our own biases.

5. Human and natural systems are not actually distinct. The concepts of nature and environment were constructed by humans so that we could better understand our surroundings. The cultural division between human and natural systems itself is an arbitrary and non-universal false dichotomy.

While we did not formally reach a consensus on how (or whether) human and natural systems can be distinguished, our back-and-forth exchange was a valuable lesson on epistemological differences. Epistemological differences can present challenges in multi- and transdisciplinary work, and it is important to be aware that in any given situation, there is not necessarily one answer or system of knowledge that is correct or shared; rather, all people possess knowledge systems that affect their world views. In research, this can impact the way that we approach problems, what methodology we employ to answer questions, and even what types of questions we ask.

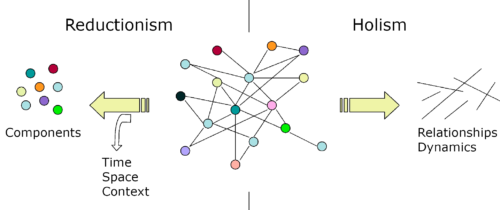

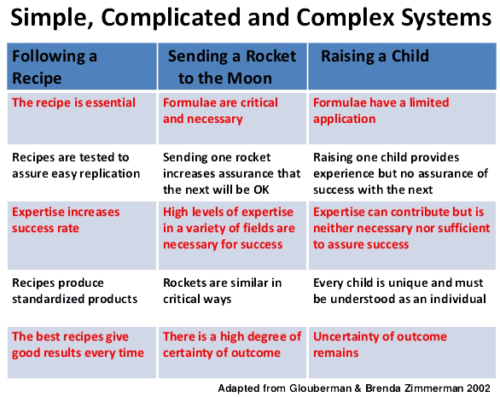

For example, perhaps instead of taking a reductionist approach of identifying the structure and function of the components of a coupled system, we should shift our focus to the processes and interactions between components within the system. Instead of thinking about just environment or just humans, for instance, we should think about environmental justice and consider how environmental outcomes have uneven consequences for different groups of people involved.

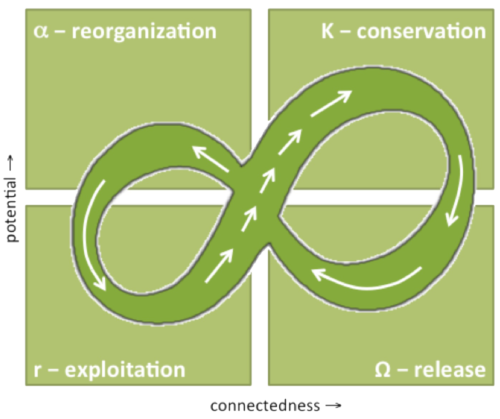

Resilience theory can serve as a framework to holistically study coupled system dynamics4. Natural or human systems are resilient when they can cope with disturbances that result from social, political, or environmental changes, and retain their same states5. Furthermore, limits of communities adapting to environmental change can be explained not only based on geographical location, but also by cultural values, social relationships, and historical context5. Resilience theory can help us ponder complex questions related to power dynamics: Who experiences change disproportionately? Do communities unaffected by disturbances have a responsibility to help those who are more vulnerable? How do the actions of unaffected people directly or indirectly contribute to the loss of resilience of other communities?

Answering these types of research questions concerning coupled human and natural systems should be approached as complex problems. As researchers, we should embrace and unpack this complexity using a thoughtful holistic approach. It is no longer sufficient to study just one part of a system; rather, we must acknowledge all interrelated components and work to understand the context of our research through a transdisciplinary lens.

References:

- Liu, J., Dietz, T., Carpenter, S. R., Folke, C., Alberti, M., Redman, C. L., ... & Taylor, W. W. (2007). Coupled human and natural systems. AMBIO: a journal of the human environment, 36(8), 639-649.

- Liu, J., Dietz, T., Carpenter, S. R., Alberti, M., Folke, C., Moran, E., ... & Ostrom, E. (2007). Complexity of coupled human and natural systems. Science, 317(5844), 1513-1516.

- Liu, J., Hull, V., Batistella, M., DeFries, R., Dietz, T., Fu, F., ... & Martinelli, L. (2013). Framing sustainability in a telecoupled world. Ecology and Society, 18(2).

- Stokols, D., Lejano, R., & Hipp, J. (2013). Enhancing the resilience of human–environment systems: A social ecological perspective. Ecology and Society, 18(1).

- Cote, M., & Nightingale, A. J. (2012). Resilience thinking meets social theory: situating social change in socio-ecological systems (SES) research. Progress in Human Geography, 36(4), 475-489.

- Gunderson, L. H. (2001). Panarchy: understanding transformations in human and natural systems. Island press.

- Glouberman, S. & Zimmerman, B. 2002. Complicated and complex systems: What would successful reform of health care look like? Romanow Papers: Changing health care in Canada. Paper 8.

Next Post > Lessons on how to synthesize science

Comments

-

Krystal Yhap 9 years ago

I really think Suzi did a wonderful job of summarizing major points that were made in both our discussion in class and our readings. When you wrote about our discussion on how human and natural systems are different it was really helpful to see the summation of the different opinions and thoughts people had. Because there was so much being said on that one specific topic during class it became hard to follow sometimes what people were trying to say but it was made more clear to me here from the way Suzi organized that part of the blog post.

I think my favorite part of the discussion we had in class was about epistemology. I think that concept is one of the reasons this class and topics we discuss are so interesting, because we have a good amount of people that come from differing epistemologies and everyone brings different approaches and thoughts to the table others may not have considered. Even just understanding the term resilience. People define and look at resilience in such different ways and a large part of it has to do with their background and research. That's why I loved the "Reality can be so complex..." picture you chose to use because it shows how our perspectives and knowledge systems impact our view and conclusions on certain topics.

-

Bill Nuttle 9 years ago

I discovered the concept of the techno-ecosystem when we were working on the Mississippi River report card (http://ian.umces.edu/blog/2014/04/01/the-ohio-rivers-split-personality/)

Eugene Odum introduced the concept of the techno-ecosystem to talk about human-dominated urban-industrial landscapes. He was adamant that techno-ecosystems should be considered distinct from "natural" ecosystems, rather than to seek some unifying conceptual way of combining the two. Doing so forces us to recognize and pay attention to what happens at the boundaries. As Robert Frost says, "Good fences make good neighbors."

Odum, E.P., 2001. The “techno-ecosystem.” Bulletin of the Ecological Society of America 82:137-138.

-

Bill Dennison 9 years ago

I agree with the lack of easy consensus on what constitutes a coupled human and natural system. The comment by Bill N. about Gene Odom's perspective illustrates how ecologists have struggled with the concept for quite some time. I really like that we are going to approach the topic from so many different perspectives this semester. Thanks to Suzi for such a good summary, great graphics and references.

-

Noelle O. 9 years ago

The main takeaway I got from the first lecture series is the unyielding interconnectedness of human and natural systems. While I have always believed interconnectedness to be true in regards to biological diversity and ecosystems, until recently, I had not fully grasped the ripple effects of humans, culture, and economics on biodiversity. As Bill so eloquently said in class, your head may “explode” when you really start to think about all the possible ways coupled human and natural systems interact. Seriously. When I began the process of preparing to lead class discussion, I felt very overwhelmed by all of the concepts introduced in the four lectures (many of which Suzi wrote about above), mostly because my schoolwork has always been so environmental science-heavy. I quickly realized that I still have a lot to learn, including new terminology, but I am very excited to see where our class discussions lead us over the next few months.

Last semester I took a marine resource policy class which really sparked my interest and first exposed me to some socio-economics of marine resources. I eventually want to work in fisheries management, and I’ve become increasingly aware of the importance of human dimensions in resource management. I love having the opportunity to work closely with commercial lobstermen for my thesis and want to work towards bridging the gap between scientists and fishermen and consumers. I’m taking this course to gain exposure to new fields of study and ways of thinking to help me become an effective manager. -

Natalie Yee 9 years ago

I agree with Krystal in that Suzi did a great job summarizing the discussion. It went over all the major topics and opinions clearly and concisely.

The discussion concerning complex systems was intriguing because even if a problem is approached in the same manner, the result may end up different because every circumstance is different. It demonstrated the complexity of natural and human systems, and brought home the point that the two may not be so distinct after all. It tied in well with our previous discussion on whether or not a natural system could continue without a human system and vice versa; that discussion tried to distinguish the two, and part of the class agreed that natural systems would be able to go on without human systems, but not the other way around. However, in discovering just how complex both natural and human systems are, this line is harder to define and opens the discussion back up.

-

Vero Leitold 9 years ago

My feelings resonate with what Noelle mentioned above about the overwhelming complexity of systems and concepts that we have talked about in class so far. Having spent most of my schooled years and research activities focused on the natural sciences (earth sciences and ecology, more specifically), I am now encountering a whole new set of vocabulary in our course readings on human and natural systems. I am still struggling a little bit with the terminology itself, because in my mind “human” and “natural” are not distinct, rather, for me, “human” IS “natural” (or “biological”?). I feel like I can make the mental distinction easier when the two parts are referred to as “social” versus “ecological”, although even then, I recall for example reading about the social life of trees (see here: https://nyti.ms/2k8cdB5 – a fascinating book, btw), or the inner workings of ant communities, etc. It is hard for me to tell where ecological/natural ends and social/human begins. I was trying to think of other word-pairs that might clarify the difference, like “organic” vs. “inorganic” or “material/physical” vs. “abstract/intellectual”?… It is interesting to hear all the different perspectives that this course brings together, and I look forward to learning more as the semester unfolds.

-

Kelly Hondula 9 years ago

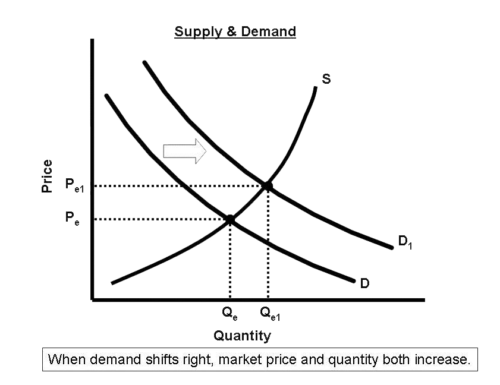

I found it interesting to think about what is considered a "law" in natural sciences vs. social sciences. Physical laws that describe behavior of objects based on mass, gravity, energy, etc. whereas economic and social laws describe the behavior of people such as the relationship between prices and supply and demand in a market ("the law of supply and demand"), or geographic phenomena such as "Tobler's law of geography". The extent to which these various laws are universal and useful for making predictions and drawing conclusions to understand coupled human and natural systems depends on the specific application and questions being asked in any particular analysis.

-

Killian F 9 years ago

I agree with Krystal that my favorite part of the in-class discussion was the part about epistemology. I think that this is something that should be discussed more in science communication classes, or in any science class, though this is the first I’ve ever really heard it talked about. I think in particular it would be useful to discuss with students from the Atmospheric and Oceanic Science department. I often see fellow students from this department engaged in debates on social media about climate change, and see the frustrations that stem from approaching this issue from different viewpoints. Attempting to argue points on climate change using the data and evidence that works well with people from an atmospheric science background may not be an effective way to engage with people with a different knowledge system and a different worldview. And when these worldview clashes lead to a stalemate in a debate, we may dismiss the other side as just being stubborn or unscientific. In order to reach understanding between everyone on issues such as these, we need take into consideration different epistemologies and remember this when approaching different problems.

-

Rachel E 9 years ago

I loved the way Suzi summarized our conversations from last week! I think that the fifth point made in our topics of how human and natural systems differ from each other - that they are not distinct at all- was the most interesting point made during the conversation! When it was mentioned that the term 'ecosystem' is a man made term used to describe these things, and that you actually could not have and 'ecosystem' without man having defined the term to begin with, I was taken aback. The response stemmed from the question "can we have an ecosystem without humans." I personally would have never thought to answer the question from this perspective. My initial response was 'yes ecosystems existed before we as humans did, so of course they can exist without us!' But after discussing the perspectives of people who approach questions from a different background and field of knowledge, my eyes were opened to look at these questions from a different angle.

As we discussed in class and Krystal mentioned in her comment - each of us has a different epistemology and each of us approaches these questions from a different angle. I hope that this weekly open discussion continues to provide eye-opening conversations!

-

Rebecca Wenker 9 years ago

I enjoyed the breakdown of our discussion on the supposed differences between human and natural systems. I think Suzi did a good job of highlighting that although they seem very different initially, they are much more similar than we thought. This discussion also highlighted how people approach topics differently, and how our thought processes vary. I believe this was an important exercise and introduction in how epistemological differences can shape even somewhat simple conversations. Imagine scaling this up to a discussion on how to reduce CO2 emissions, or something similarly complex!

-

W.Cruz 9 years ago

Great blog! In terms of resilience when you cite: "return to same states" other definitions of resilience don't refer to return to the same state if not being functional after disturbances. Moreover, when you ask if "Do communities unaffected by disturbances have a responsibility to help those who are more vulnerable?" it is indeed an interesting concept because often people don't empathized unless they have been through the same situations. I enjoy your conclusion and agree that it's important to look at the environment as whole and use the transdisciplinary lents to work with this type of scenarios.

-

David Miles 9 years ago

Human-natural coupled systems are ubiquitous; they support the world’s economy and make our civilization possible. Our class session really showed how hard it is to wrap one’s head around such complex systems. There seem to be endless approaches one can take when trying to understand them. As a new researcher, I am excited to be given the chance to study aspects of such systems. However, making a real difference in how these systems operate must necessarily involve many stakeholders that do not come from research backgrounds. Researching to satisfy curiosity is one thing, but effecting positive change in policy is another. The part of the blog discussing reductionist versus holistic approaches to research really resonated with me. I believe using more holistic research techniques that bring relationship dynamics to the forefront may be a good approach to educating the various stakeholders so they may make better decisions. Reductionist approaches, while useful and necessary, may not resonate with the breadth of stakeholders like a holistic approach might.