History and Structure of the Chesapeake Bay Program

Wyatt Palenchar · 8 commentsWho they are

The Chesapeake Bay Program is a partnership of numerous stakeholders that work collaboratively to restore and protect the Chesapeake Bay ecosystem. This partnership comprises over 19 federal agencies, 40 state agencies, 1,800 local governments, 20 different academic institutions, and over 60 other organizations and businesses.1

How they work

The Chesapeake Bay Program has been successful due to its structure and the six core agreements that act as a guide by laying out their goals. This structure and smart planning are what enable so many different stakeholders to come together and work toward a common goal.

Agreements

- The first agreement came in 1983 between the states of Maryland, Pennsylvania, and Virginia, the mayor of Washington, D.C., the EPA, and the chair of the Chesapeake Bay Commission. This Agreement was the first step in helping to establish the Chesapeake Bay Program, as it acknowledged the need for a partnership to effectively address the bay's pollution. These original signers became the Chesapeake Executive Council; one part of the overall structure that makes the Program so effective.2

- The 1987 Chesapeake Bay Agreement was instrumental in furthering the goals of the Chesapeake Bay Program, as it established clear goals with specific deadlines. One of these goals was to implement a plan to reduce the nitrogen and phosphorous entering the Bay by 40% by the year 2000 and to re-evaluate the target of this goal by December 1991. Other goals included establishing a strategy by December 1991 to encourage local governments to protect wetlands and other fragile ecosystems through their planning processes and to establish an annually reviewed research plan to accurately address the needs of the Chesapeake Bay by July 1988.2, 3

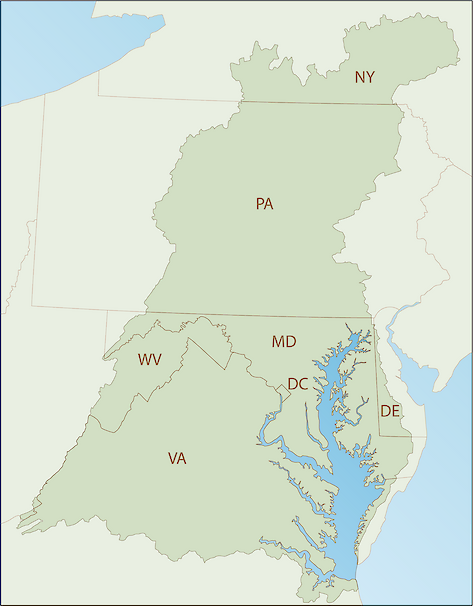

- The Chesapeake 2000 agreement was made in 2000 and evolved from earlier agreements by including 102 different goals to help restore the Bay by the year 2010. This agreement also extended the efforts of the Program to improve water quality to Delaware, New York, and West Virginia by each state’s governor adding their signature. These new additions made it so all states in the Chesapeake Bay watershed were involved in helping to improve the Bay’s water quality.2

- In 2009, President Barack Obama made Executive Order 13508, which highlighted the national importance of the Chesapeake Bay and called on the federal government and its agencies to increase their restoration and protection efforts of the Bay. This executive order included the collaboration between federal agencies and other partners and addressed issues such as water quality, agricultural practices, reducing pollution from federal facilities in the Chesapeake Bay Watershed, protecting the bay as the impacts of climate change worsen and change over time, to improve the public’s access to the Bay, to provide resources to support ecosystem management, and to restore and protect living resources.2 ,4 ,5

- The following year, the EPA established the Chesapeake Bay Total Maximum Daily Load (TMDL), which established limits for nitrogen, phosphorous, and other pollutants for the Bay and its tributaries, and established a deadline for all strategies to meet these limits to be implemented by 2025. This also led the six states and Washington D.C. to establish specific plans called watershed implementation plans (WIPs) that laid out how they would work to meet these limits. Part of this includes the use of short-term restoration goals, often called 2-year milestones, to assess the progress toward the limits set by the EPA in 2010. The Chesapeake Bay Program was instrumental in this process, as it facilitated the collaboration between local governments, state agencies, and federal agencies. This method of synthesizing and applying science, seen here, is a common method used by the Chesapeake Bay Program and is yet another reason why it has been so effective.2, 6, 7

- The Chesapeake Bay Watershed Agreement was signed in 2014 and was further amended in 2020. As in previous agreements, this agreement also outlined goals and outcomes for the restoration of the Bay. However, it differs in that it officially brought in Delaware, New York, and West Virginia to be full partners in the Chesapeake Bay Program. This was crucial as it ensured the entire watershed was involved in the restoration and protection of the Chesapeake Bay. Furthermore, this agreement was also important because it focused more on the use of adaptive management than previous agreements. 2, 8

Structure

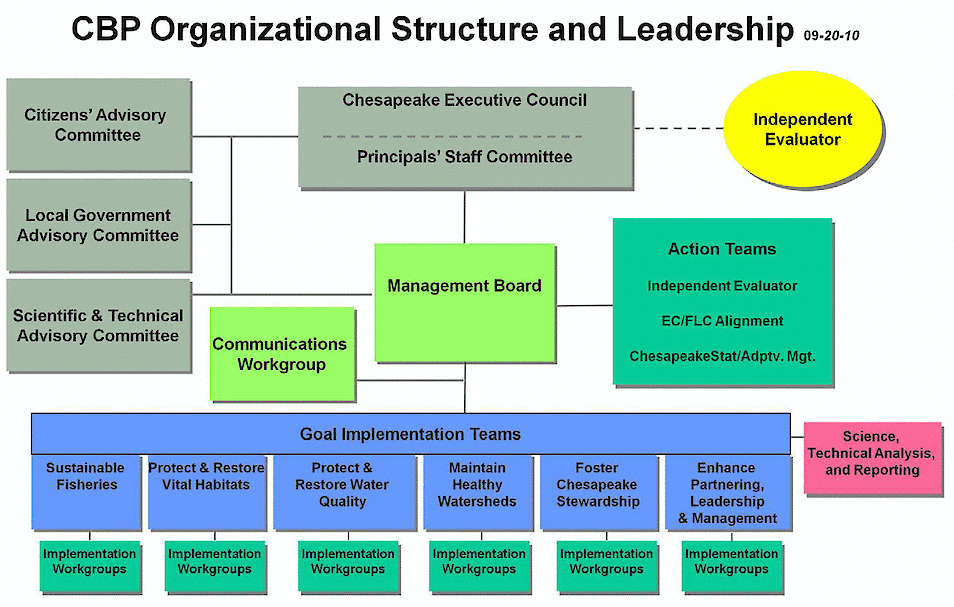

Structure is an important part of the Chesapeake Bay Program, due to the sheer number of stakeholders involved. The structure of the Chesapeake Bay Program includes many different groups with their own specific responsibilities, all of which are crucial for the Chesapeake Bay Program to remain effective in restoring and protecting the Chesapeake Bay and its watershed. The different components of the Chesapeake Bay Program structure include:

- The Executive Council: Made up of the 6 governors of each state, the mayor of Washington D.C., the administrator of the EPA, and the chair of the Chesapeake Bay Commission; and determines the direction the Program will take to restore and protect the Bay. The council also plays a key role in communicating progress toward restoring and protecting the Bay with the public. This allows the public to see how the Program is actively working to improve the health of the Bay and helps hold the program accountable by being transparent with the public.9, 10, 11

- The Principals’ Staff Committee: Acts as advisors on policy to the Executive Council and helps guide the Management Board on policy.10, 11, 12

- The Management Board: Works to plan and implement the goals outlined in the different agreements.11,13

- Advisory committees: Advises the Executive Council, the Principals’ Staff Committee, and the Management Board on a wide variety of topics regarding stakeholders, local governments, and science and technology. These committees ensure that the community’s concerns are addressed, the Program is transparent to the public, local governments are involved in the restoration and protection of the Bay, and that strategies that are implemented are backed and based on science. 11, 14, 15, 16

- Goal Implementation Teams: Teams made up of further working groups and committees that are dedicated to a specific topic related to the health of the Bay and focus on strategies to achieve specific goals within their dedicated field. These topics include habitat, water quality, maintaining healthy watersheds, fostering stewardship, and enhancing partnership, management, and leadership. 10, 11

- The Strategic Engagement Team: Help Goal Implementation Teams when there is additional support for communication, social science, stewardship, and engagement with local governments is needed. 11, 17

- The Scientific, Technical Assessment and Reporting (STAR): Works to provide the monitoring and analysis that policy and different strategies are based on. They also provide the data that is used to communicate the changes in the Bay and the progress of the Chesapeake Bay Program to the public.10, 11, 18

This structure helps to ensure that the appropriate stakeholders are involved and are able to interact with other stakeholders to help shape policy and strategies that are based on shared ideas and science from a wide range of fields.

References

- Our partners. Chesapeake Bay Program. (n.d.-j). https://www.chesapeakebay.net/who/partners

- Our history. Chesapeake Bay Program. (n.d.-i). https://www.chesapeakebay.net/who/bay-program-history

- 1987 Chesapeake Bay Agreement. Chesapeake Bay Program. (n.d.-a). https://d38c6ppuviqmfp.cloudfront.net/content/publications/cbp_12510.pdf

- Guidance for Federal Land Management in the Chesapeake Bay Watershed. EPA. (n.d.). https://www.epa.gov/sites/default/files/2015-10/documents/chesbay_chap01.pdf

- National Archives and Records Administration. (n.d.). Executive order 13508-- Chesapeake Bay Protection and Restoration. National Archives and Records Administration. https://obamawhitehouse.archives.gov/realitycheck/the_press_office/Executive-Order-Chesapeake-Bay-Protection-and-Restoration

- Chesapeake Bay TMDL. Chesapeake Bay Program. (n.d.-b). https://www.chesapeakebay.net/what/programs/total-maximum-daily-load

- Watershed Implementation plans. Chesapeake Bay Program. (n.d.-p). https://www.chesapeakebay.net/what/programs/watershed-implementation-plans

- Chesapeake Bay Watershed Agreement. Chesapeake Bay Program. (n.d.-c). https://www.chesapeakebay.net/what/what-guides-us/watershed-agreement

- Chesapeake Executive Council. Chesapeake Bay Program. (n.d.-d). https://www.chesapeakebay.net/who/group/chesapeake-executive-council

- Governance and Management Framework for the Chesapeake Bay Program. Chesapeake Bay Program. (n.d.-e). https://www.chesapeakebay.net/files/documents/CBP-Governance-Document-Version-5.0_2023-06-14-134248_nimt.pdf

- How we’re organized. Chesapeake Bay Program. (n.d.-f). https://www.chesapeakebay.net/who/how-we-are-organized

- Principals’ staff committee. Chesapeake Bay Program. (n.d.-k). https://www.chesapeakebay.net/who/group/principals-staff-committee

- Management Board. Chesapeake Bay Program. (n.d.-h). https://www.chesapeakebay.net/who/group/management-board

- Local Government Advisory Committee. Chesapeake Bay Program. (n.d.-g). https://www.chesapeakebay.net/who/group/lgac

- Scientific and Technical Advisory Committee. Chesapeake Bay Program. (n.d.-l). https://www.chesapeakebay.net/who/group/stac

- Stakeholders’ advisory committee. Chesapeake Bay Program. (n.d.-n). https://www.chesapeakebay.net/who/group/stakeholders-advisory-committee

- Strategic engagement team. Chesapeake Bay Program. (n.d.-o). https://www.chesapeakebay.net/who/group/strategic-engagement-team

- Scientific, technical assessment and reporting (STAR). Chesapeake Bay Program. (n.d.-m). https://www.chesapeakebay.net/who/group/scientific-and-technical-analysis-and-reporting

About the author

Wyatt Palenchar

Wyatt Palenchar is a first-year master’s student in the Marine-Estuarine Environmental Sciences Program at the University of Maryland Eastern Shore. He received his bachelor’s degree from the University of Maryland, College Park in Environmental Science and Technology. He is currently studying the diets of coastal predatory fish using metabarcoding and next-generation sequencing.

Next Post > Climbing Down the Ivory Tower

Comments

-

Zhongshi He 11 months ago

This is a well-researched and well-organized overview of the Chesapeake Bay Program! You did a great job highlighting not only the history of key agreements, but also the evolving and inclusive nature of the partnership over time. I especially appreciate how you demonstrate the organizational structure, and it really helps convey the complexity and collaborative strength of the Program. The emphasis on adaptive management, transparency, and science-based policy is particularly inspiring and shows why the Chesapeake Bay Program is a model for large-scale environmental restoration efforts. Excellent work!

-

George Anim Addo 11 months ago

This is a well-researched and clearly written article that provides a solid understanding of the Chesapeake Bay Program. You've done a good job of explaining a complex organization and its history in an accessible way.

-

Sabine Malik 11 months ago

Hello! This is a great summary of the Chesapeake Bay Program. Before starting to work in environmental science in the area, I had no idea that the Bay Program was federally backed and EPA sanctioned. I think this is in part due to what we discussed in our class, which is that there are lots of Chesapeake Bay organizations that sound similar. It will be interesting to see how the 2025 goals that have not yet been met will be adapted and re-strategized moving forward.

-

Lina Goetz 11 months ago

Great Job on your blog post, your overview of the Chesapeake Bay Program was very informative and easy to follow.

-

Vanessa Mukendi 10 months ago

Wyatt, Great job on this blog post! I think you clearly outlined the agreements. It gave a good historical context of the program. I also think the structure definitions combined with the chart was helpful to see how the program stucture is laid out with a focus on diverse stakeholders.

-

George Anim Addo 10 months ago

This is a strong and accurate summary, it effectively conveys the history and complex organizational framework of the Chesapeake Bay Program. You've done a good job of extracting the key information and presenting it in a clear and organized way.

-

M.J. Parsons 10 months ago

You did a great job communicating the history and structure of this organization. It is incredible to see the reach of this program and can understand why they have had great success since their inception.

-

Wyatt Palenchar 9 months ago

Hello, please note that the offices of the Chesapeake Bay Program have since moved, and that the diagram of the structure of the Program provided is an earlier iteration and has been somewhat revised.