Indian River Lagoon: Environmental Literacy

Bill Nuttle · | Environmental Literacy | Learning Science |The concept of environmental literacy derives from a series of programs that have established various literacy principles, for example, Ocean Literacy and Chesapeake Bay literacy. Literacy principles form the framework, but it is the richness of examples, stories and visual supporting materials that enliven the understanding of our environment.

The seven principles that an informed person needs to know about the Indian River Lagoon are:

- The Indian River Lagoon (IRL) lies between the mainland and the barrier islands along the middle one-third of Florida’s Atlantic coast.

- The IRL is ecologically diverse; over 3500 species can be found here including many that are iconic of Florida.

- The IRL straddles the boundary between the temperate and tropical climate zones.

- The health of the IRL ecosystem depends on the extent and condition of its seagrass beds and fringing wetlands.

- The physical characteristics of the IRL make it susceptible to developing conditions that allow blooms of phytoplankton to develop and persist.

- The IRL ecosystem is vulnerable to the impact of human activities in the lagoon and the watershed.

- Recent changes in the IRL ecosystem heighten concerns that the IRL ecosystem has been pushed to a tipping point.

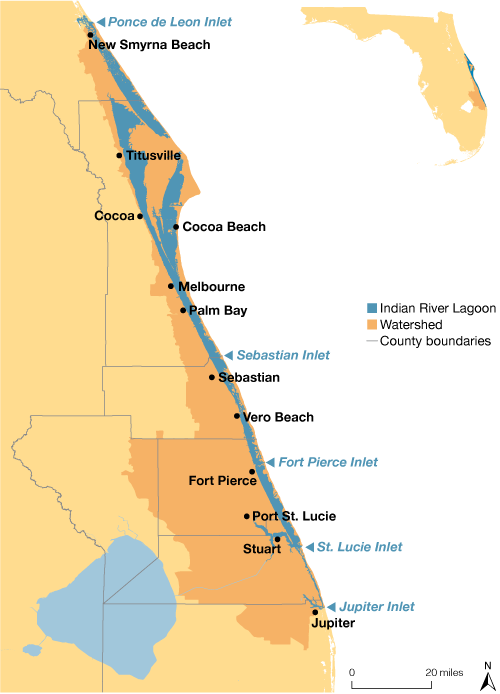

1. The Indian River Lagoon (IRL) lies between the mainland and the barrier islands along the middle one-third of Florida’s Atlantic coast. Stretching 156 miles, from Ponce de Leon inlet at its north end to Jupiter inlet in the south, the IRL is nearly as long as the main stem of the Chesapeake Bay. Its natural watershed occupies a narrow band mostly within 20 miles of the coast. Nearly one million people live and work near the IRL, but over 10 million people visit the region for recreation each year. The IRL supports a $300 million fishery industry and $300 million in boat and marine sales.

2. The IRL is ecologically diverse; over 3500 species can be found here including many that are iconic of Florida. The IRL is home to about a third of the nation’s manatee population, and it hosts a resident population of between 200 and 800 Bottlenose dolphins. The barrier islands provide nesting habitat for sea turtles, including 4 species on the endangered list. Visitors can see Wood storks, Brown pelicans, and Roseate spoonbills, and anglers can fish for Tarpon, Red Drum and Spotted sea-trout.

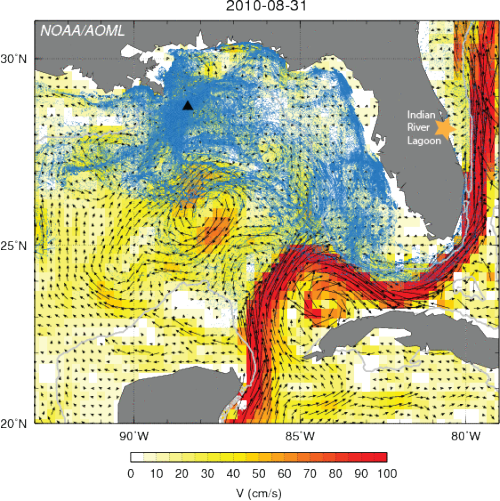

3. The IRL straddles the boundary between the temperate and tropical climate zones. This explains the vast diversity of species found here, and it makes the IRL a barometer for climate change. Many of the fish found in the lagoon migrate to the ocean to spawn, and the larvae return inshore to use productive seagrass beds as nursery habit. Larvae of tropical species are carried north into this area by the Gulf Stream, and the prevailing inshore coastal currents carry temperate species into the area from the north. As temperatures warm, more and more tropical species are able to survive in the IRL waters. Similarly, the tropical mangrove species have moved northward over the past 20 years, increasing the area of mangrove swamp wetland around the IRL.

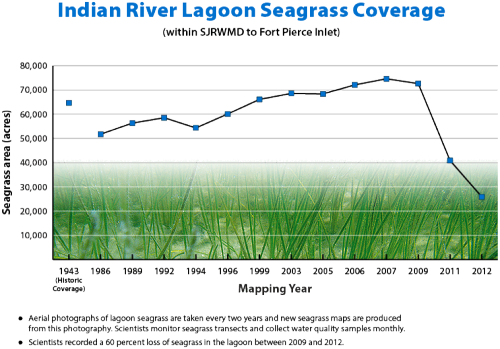

4. The health of the IRL ecosystem depends on the extent and condition of its seagrass beds and fringing wetlands. Seagrasses form the base of the food chain, and they serve as essential nursery habitat for fish and shellfish. The wetlands surrounding the lagoon stabilize the shoreline and help maintain water clarity by regulating the inflow of sediment and nutrients. Nutrients have a negative impact on the seagrass beds by stimulating the growth of phytoplankton in the water column. High concentrations of phytoplankton and suspended sediment decrease the amount of light that reaches the bottom, and this can cause a loss of seagrass. However, it is possible that plankton blooms leading to the occasional loss of seagrass have always occurred naturally in the IRL.

5. The physical characteristics of the IRL make it susceptible to developing conditions that allow blooms of phytoplankton to develop and persist. The IRL is shallow and poorly flushed, averaging only about 4 feet deep. Over a year is needed for tides and wind-driven circulation to flush areas in the northern section of the IRL. Wind-driven circulation and storms are important. Flushing times for the central and southern portions vary from months to weeks. Well-flushed conditions occur locally, near the few tidal inlets that cut through the barrier islands.

The IRL receives little inflow of freshwater from the watershed, with the exception of the St. Lucie River, and the effect of inflow on flushing is localized. Hypersaline conditions can develop in the north during periods when evaporation exceeds total freshwater inflow. Flow in the St. Lucie River is affected by managed discharges of water from Lake Okeechobee. Extremely high inflows of freshwater occur that are damaging to populations of estuarine species in the lagoon. However, most of the inflow exits through the St. Lucie inlet during high rates of inflow, and impacts on the ecology of the lagoon are limited to the vicinity of the river mouth.

![St. Lucie Inlet Near Shore Reef: Before and During Discharges. Credit: Florida Oceanographic Society [pdf]. St. Lucie Inlet Near Shore Reef: Before and After Discharges](/site/assets/files/2508/discharges-500x273.png)

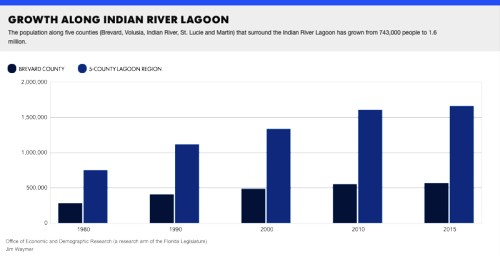

6. The IRL ecosystem is vulnerable to the impact of human activities in the lagoon and the watershed. Development around the lagoon has replaced wetlands with seawalls and other types of hardened shoreline structures and created networks of canals that are hotspots for pollution. Regional water management activities have altered the lagoon’s hydrology by introducing large inflows of water from Lake Okeechobee and parts of the St. Johns River watershed, effectively increasing the size of the IRL watershed. The number of people living around the IRL doubled in the period 1980 to 2015, and growth is expected to continue. Accompanying changes in land use, such as the conversion of wetlands for agriculture and urban development, have increased the flow of nutrients and sediment into the lagoon.

![The Indian River Lagoon Watershed had increased over the years. Credit: The Indian River Lagoon Comprehensive Conservation and Management Plan [pdf]. The Indian River Lagoon Watershed had increased over the years.](/site/assets/files/2508/screen-shot-2016-02-10-at-1_10_17-pm-500x702-1.png)

7. Recent changes in the IRL ecosystem heighten concerns that the IRL ecosystem has been pushed to a tipping point. Actions taken in 1990 to reduce the impact of human activities on the lagoon seemed to be working. Seagrass beds expanded in coverage to the extent last seen in the 1940s. But, signs of ecological distress appeared in 2011, when a “superbloom” of phytoplankton caused a dramatic loss of seagrass. The blooms have persisted since then. Then, in 2012 and 2013, large numbers of manatees, dolphins and pelicans were found dead. So far, investigations have failed to uncover a single cause for this crisis. Many fear that the ecosystem has been pushed to a tipping point. Widespread concern motivates increased efforts to reduce the impacts of human activities on the lagoon and restore its natural functioning.