Israelis working with Palestinians for ecosystem restoration

Bill Dennison ·As we continue to watch the horrible news from the Middle East, I have been reflecting on my experiences with environmental restoration efforts that have served to unite, rather than divide people in the region. There is a story that I want to share that may provide some hope in this bleakest of times.

When I was based in Australia, we created the International RiverFoundation to champion integrated river basin management of the world’s rivers. I still serve on the Board of Directors for this foundation, and we convene the annual International RiverSymposium and award the prestigious Thiess International RiverPrize for excellence in river management. I enjoy these symposia and prizes because they focus on knowledge and wisdom sharing (as opposed to many scientific symposia in which the focus is on data and information sharing). These symposia always provide inspiration for me, especially the stories associated with the winners and finalists of the Thiess International RiverPrize.

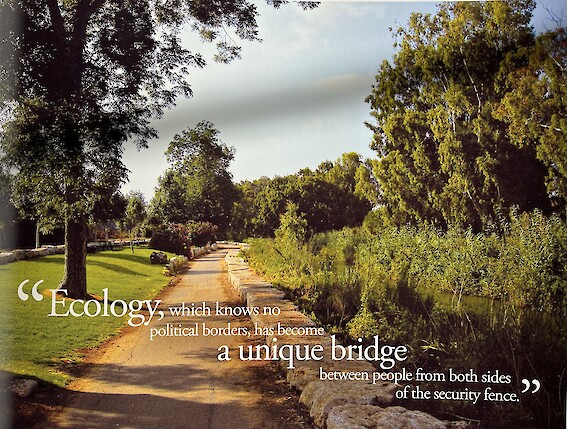

One of the most powerful restoration stories was that of the Alexander River (Nahar Alexander in Hebrew and Nahar Iskandar in Arabic). The Alexander River has its origins in the Palestinian territories of the West Bank from the Palestinian city Nablus and flows 45 km (28 miles) through Israel’s Emek Hefer Regional Council to the Mediterranean Sea. It was one of the most polluted rivers in the region, and it is the habitat of the giant African soft shell turtles.

The Alexander River effort was spearheaded by the Alexander River Restoration Administration, initiated in 1995, and it includes various Israeli government agencies, but importantly, includes the Palestinian district and town of Tul Karem. This joint environmental restoration effort included sewage treatment upgrades, riverbank restoration and the creation of recreational facilities along the restored stretches of the river. Some of the sewage upgrades were funded by German government, demonstrating the international nature of ecological restoration. Some of the riverbank restoration efforts needed giant cloth screens erected to protect the people from sniper fire. I also learned that no one would harass the people spraying for mosquitos – a common enemy of the residents. I often use this example when people in Chesapeake refer to the Civil War over a hundred and fifty years ago as an excuse for the lack of cooperation—if the Israeli and Palestinian people restoring the Alexander River can brave sniper fire, we most assuredly can look beyond our historic differences in Chesapeake region to work together.

When the delegation of Israelis and Palestinians came to Brisbane, Australia in 2003 to receive the Thiess International RiverPrize, I met an architect who was the chief planner of the Alexander River Restoration Project, Amos Brandeis. I would catch up with Amos when we returned to many subsequent RiverSymposiums, including the most recent one held in Vienna, Austria in December, 2022. He was one the first people I reached out to when I learned of the horrible events in the region, and fortunately Amos and his family were safe.

The lesson I take away from the Alexander River restoration is that ecosystem restoration can indeed unite people beyond their political differences. If we look forward to the global challenges that we face as a result of climate change and population pressures, we need to build on the experiences like the Alexander River to overcome our differences, and unite to address these challenges. Our new University of Maryland Center for Environmental Science’s initiative, the Chesapeake Global Collaboratory, will take this to heart and work to bring diverse people together to tackle the grand environmental challenges that we are facing.

About the author

Bill Dennison

Dr. Bill Dennison is a Professor of Marine Science and Vice President for Science Application at the University of Maryland Center for Environmental Science.