Lessons learned from the Sunbelt Social Network Conference

Vanessa Vargas-Nguyen · | Applying Science | Learning Science |During the opening ceremony of the Sunbelt Social Network Conference that I attended last June (you can read my conference experience here), the article “Twenty years of Network Science” was mentioned. It emphasized the 20 years since Watts and Strogatz introduced the ‘small-world’ model of networks, which initially was viewed only as the explanation for the popular social network idea of Six degrees of Separation. Soon after, however, it became apparent that the dynamics of these “small-world” networks are actually reflected in real-world systems. Despite the almost 100 years of empirical studies using network methods in the social sciences, it was the 1998 paper of Watts and Strogatz that established network science as a multidisciplinary field. It became the basis for many studies, from the spreading of epidemics, information diffusion, understanding the structure of the world-wide web, and even how the brain network functions, among others. In the same way, the role of network typologies in solving complex environmental problems is starting to become an emerging field and is thus a powerful tool that can be applied in our work here at the Integration and Application Network (see my previous blogs here and here).

My initial interest in social network analysis started with stakeholder analysis and has now led me to this broader literature of transdisciplinary science, shared governance, and institutional fit or the idea that institutional arrangements should match “the defining features of the problems they address” (Young 2008:20). In this blog, I will add and expand on these aforementioned thoughts with lessons learned from the recent Sunbelt Conference, where I primarily attended the Network Approaches for Understanding Collaborative Environmental Governance session. The goal of the session was to feature strategies for understanding and improving the efficacy of collaborative environmental governance, which is characterized-- and often even hindered-- by complex and fragmented institutional arrangements. There were two main points that I took away from the talks in this session over four days.

First, the relationship between network structure and governance variables such as cooperation, collaboration, information sharing, social and ecological outcomes etc., like most things, is never straightforward. Depending on the system and environmental issue that is being addressed, governance networks can form and function differently. One of the most common research questions in this context is “why do people choose to collaborate with certain others to solve shared/common environmental problems?”. Orjan Bodin of the Stockholm Resilience Center hypothesized that people’s choice for collaborators can depend on three things: (1) basic social preference i.e. similarity; (2) desire to solve the common problem i.e. perceive effectiveness to achieve the goal; (3) perceived risk of collaboration or collaboration uncertainty. Understanding what drives (or impedes) collaboration can optimize relationships that can potentially lead to collective action and behavior change.

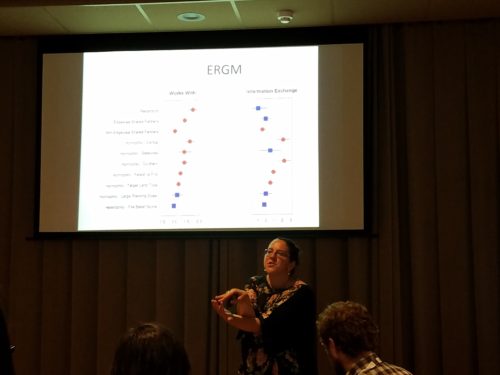

Another common issue is the mechanism of information sharing. As an example, Sara Dewachter of the University of Antwerp showed the difference between the theoretical and information sharing network in the Ugandan rural water service sector. They were able to identify the missing links and potential bottlenecks in the information flows and propose measures to improve the communication network which can ultimately lead to better rural water services provision. Other talks, such as that of Lorien Jasny and Jacob Hileman, centered on how network properties contribute to the social capital that can influence environmental problem solving. Tyler Scott presented how they compare different National Marine Sanctuary Policy Networks using the “Risk Hypothesis” (Berardo and Scholz) by analyzing the frequency of open network structure, mostly associated with learning and coordination, and closed network structures, mostly associated with cooperation problems.

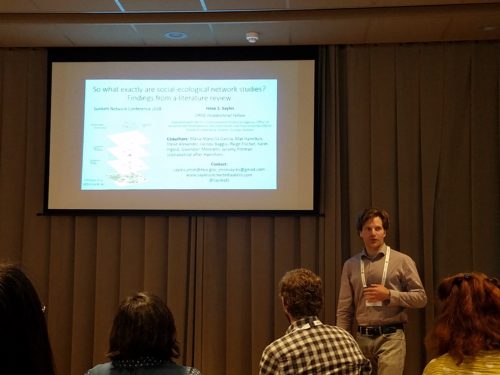

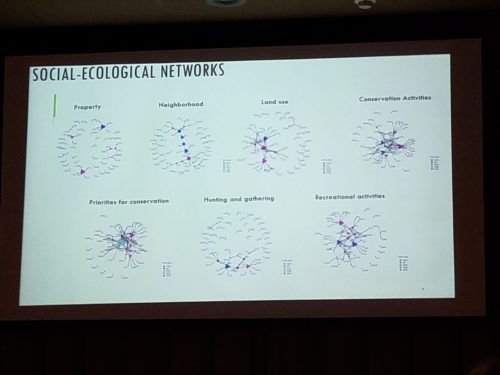

Second, it is important to understand how collaboration and other type of networks can improve governance of boundary spanning ecosystems. According to Epstein et al 2015, there are three general types of fit between institutions: (1) Ecological fit, or the fit between institutions and ecological problems; (2) Social fit, or the fit between institutions and social systems; and (3) Social–ecological system fit, or the fit between institutions and contexts that contributes to success. This social–ecological system fit is an emerging field of research and the subject of a number of presentations during the Sunbelt Conference, including mine. Jesse Sayles presented the preliminary results of their literature review of socio-ecological network studies, with the main goal of articulating how and why socio-ecological networks can help bridge the science-policy interface and link the strengths and limitations of these approaches to different kinds of environmental problems. Once published, this paper has the potential to guide and shape this emerging field. Another promising paper was on the socio-ecological network of the Payment for Hydrological Services (PHS) in Mexico presented by Adriana Aguilar-Rodríguez. Although the results were preliminary, they were able to show the importance of collaboration and information exchange networks in maintaining connectivity between upstream and downstream communities. They were also able to identify areas in which there is a mismatch between social-ecological connectivity and water provision. Similarly, with our work at IAN, being able to identify this mismatch can help in prioritizing problem areas that, when addressed timely, can lead to improving ecosystem conditions.

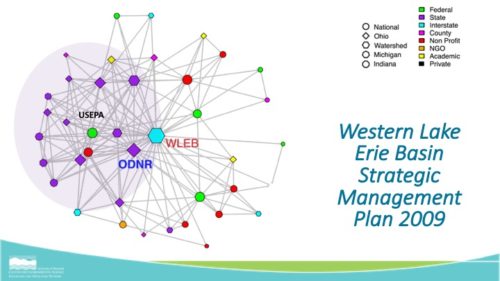

I presented the preliminary results of the SESYNC Graduate Student Pursuit project that I was a part of ("Moving beyond random acts of restoration to robust adaptive resilience: a case comparison between the U.S. and Canadian coasts of Lake Erie"). The aim of our research is to address the complex multi- and often mismatched-scales between governing institutions and ecological systems in Western Lake Erie. I will be writing a blog on the progress of our research and my experience in this student pursuit project in the future. As part of my presentation, I created a stakeholder network for the US side of Western Lake Erie Basin (WLEB) that can potentially help IAN in preparation for the upcoming Western Lake Erie Report Card project. This network map shows the primary stakeholders and their relationship based on the 2009 WLEB Strategic Management plan. The central stakeholder group is the Western Lake Erie partnership, but, as can be seen in the prevalence of purple nodes, state level stakeholders, including the state of Ohio, are also prominent. Other stakeholder groups, such as non-profits, academic institutions, and even federal agencies, are in the periphery.

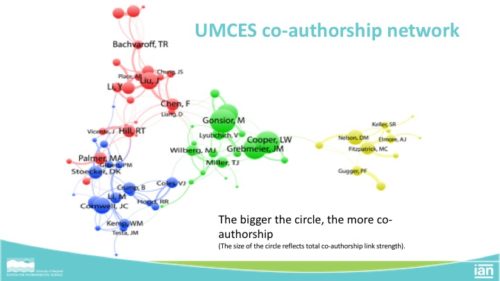

There were other sessions I attended during the Sunbelt Conference that I felt could help in other aspects of our work in IAN. Recently, IAN had started doing a report card on itself and is now in the process of developing an institutional assessment for the University of Maryland Center for Environmental Science. Social Networks Analysis is a popular tool in studying organization dynamics and even in institutional assessment and evaluation. In fact, a majority of the talks during the Sunbelt Conference was on organizational networks. The two sessions I focused on, however, were on scientific networks and on collaboration networks and knowledge diffusion. The talks were very interesting and ranged from investigating why scientists collaborate with each other, how social networks can help in getting grants, how institutional interdisciplinary collaboration can be evaluated, and even why scientists hide information from each other! One popular tool in understanding scientific collaboration is mapping scientific bibliographies. From these talks, I was inspired to create a partial UMCES co-authorship network from the Web of Science bibliographic records of the last 5 years using the basic search term of "University of Maryland Center for Environmental Science" under the organization category. Using this kind of analysis, it is possible to develop indicators for institutional assessment.

Other sessions that caught my interest were Words and Networks and Spatial Agent-Based Modelling. The session on Words and Networks was dedicated primarily to text analysis (including discourse analysis, content analysis, text mining, and natural language processing) using networks. For my dissertation, this is helpful in developing cognitive maps from interviews and survey data that can contribute to my analysis of socio-ecological system fit. Another potential application in IAN is studying communication networks and analyzing social media data. I have been interested in Spatial Agent-Based Modelling in the context of collective action and behavior change in socio-ecological systems. I also attended a short course on this topic last June, which I will be writing about in a future blog.

Indeed, Social Network Analysis and Socio-ecological Network Analysis are powerful tools that have the potential to be used not only in research but also in practice! As I have previously concluded in my previous blog, if people are connected to everyone by six degrees of separation (Stanley Milgram) and influence those up to three degrees (Christakis and Fowler), then tapping into the power of social networks can certainly make a difference!

About the author

Vanessa Vargas-Nguyen

Dr. Vanessa Vargas-Nguyen is a Science Integrator with the Integration and Application Network and an associate faculty of the Marine Estuarine and Environmental Science Graduate Program. Her current interest is in transdisciplinary approaches, socio-environmental assessments, socio-environmental justice, stakeholder engagement, and adaptive environmental governance. Vanessa is originally from the Philippines and has extensive experience in molecular biology and marine science, specializing in microbial communities and molecular processes associated with Harmful Algal Blooms and shrimp, corals, and human diseases. She has since shifted her focus on how science can benefit society and was conferred with the first Ph.D. under the new Environment and Society foundation of the MEES graduate program. Her dissertation used ethnographic approaches to investigate the role of socio-environmental report cards in transdisciplinary collaboration and adaptive governance for a sustainable future. She received academic training from the University of the Philippines (BSc; MSc) and the University of Maryland (MSc; PhD). She is involved in developing holistic socio-environmental assessments for complex systems such as the Mississippi River and Chesapeake Bay watersheds and is coordinating a multi-year international transdisciplinary research consortium involving the US, Norway, Philippines, Japan, and India.