Let’s Learn Things We Never Knew, We Never Knew

Nicole Holmes ·I know, I know. The Disney film “Pocahontas” is definitely not the most accurate recounting of the colonization of the Powhatan Indians, but the message it relays is important: Take the time to get to know someone from the perspective of their daily life, and you may learn things you never knew might be their daily struggles and solutions. Plus, who could resist Meeko and Flit?

A major topic of discussion in our latest Environment and Society class period was the alternative (and sometimes unifying) perspectives that can be provided by indigenous/aboriginal groups, as portrayed in The Meaning of Water to Health by Veronica Strang, People into Places by Maurice Bloch, and Interest in Cattle by E. E. Evans-Pritchard. However, when non-indigenous people have reached out to various indigenous communities, does that mean our work is done? I think people placing more value on indigenous perspectives should be at the same level of priority and investment as being more environmentally friendly or more sustainable in living; our work, humanity’s work, will never be done, because we will always be able to do better.

These cattle are a part of the Nuer community, and are mourned as family members in their death. “Photo” by T U R K A I R O is licensed under CC BY 2.0.

In the last century, the United States has made an effort to right the wrongs of the colonization of Native American peoples. Some examples of this are the creation of the Bureau of Indian Affairs, dedicating reservation land so that recognized tribes can operate as sovereign nations, and allocating funds to assist with hardship.1 Though these are noble efforts in reparation to the traumas of the past, the United States continues to take advantage of our Native people in several ways. Some examples of this are the use of their native lands without permission from the tribal nation, limiting their efforts to be economically independent by denying their enterprising plans, and violating trust agreements.

The inspiration for this blog was a personal issue for me. I am a member of the Penobscot-Passamaquoddy tribe, a merged tribe who has recently felt the injustice of the state government of Maine. In order to become more economically independent, my tribe as well as the others have worked together and have gone through the legal hoops with the state of Maine to put casinos on THEIR (allocated) reserved land. This year, the Governor of Maine vetoed the bill that would allow all recognized tribes in Maine to do so, and offered little more than lip service to excuse it.2 Many tribes across the nation are affected by rulings such as this, and many of them also have struggling economies with little support from the governments that continue to “make-up” for the genocide that is this country’s history.

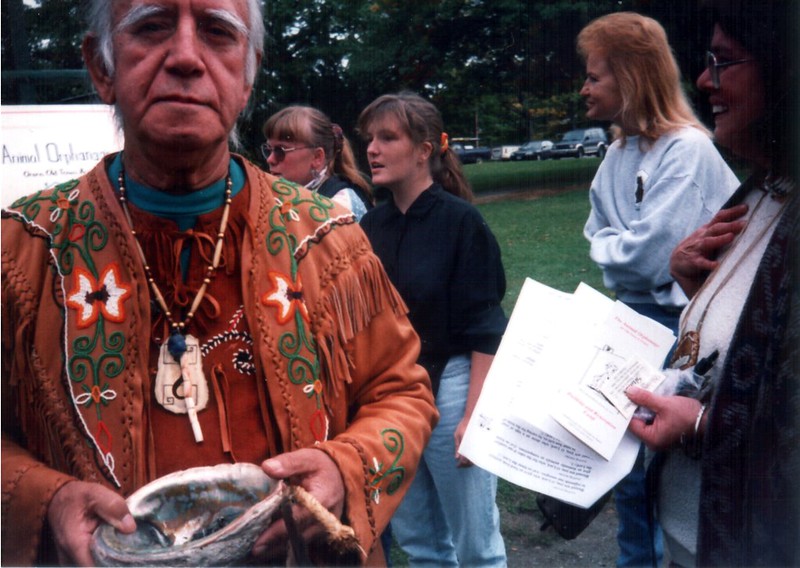

My Uncle Arnie, late Chief of the Penobscot Nation, giving the ceremonial blessing of the animals. “oct97-0012” by Terry Ross is licensed under CC BY-SA 2.0.

For those of you who have not heard of her, Elouise Cobell is a very memorable name in Native American politics. She began a long overdue and long-term class-action lawsuit against the government in the name of all Native Americans affected by the poor documentation and mismanaged accounts that the United States government held in the Individual Indian Money Trusts—trusts that were created so that the land stolen from natives could be seen as an investment for them. This was largely false, as a majority of beneficiaries never saw a dime. Instead, the U.S government used that money to pay down national debt, and destroyed important records that properly managed the ownership of the money. Elouise died just after the long-fought battle, from 1996–2011, was over; yet, she had won the battle and successfully forced the U.S. government to take responsibility for their actions.3 This is a situation that was resolved, yes. However, there are more negligent, government-derived situations like this happening every day. Right now, another group of natives is facing an injustice, and they don’t have somebody with the know-how to help them legally, not yet.

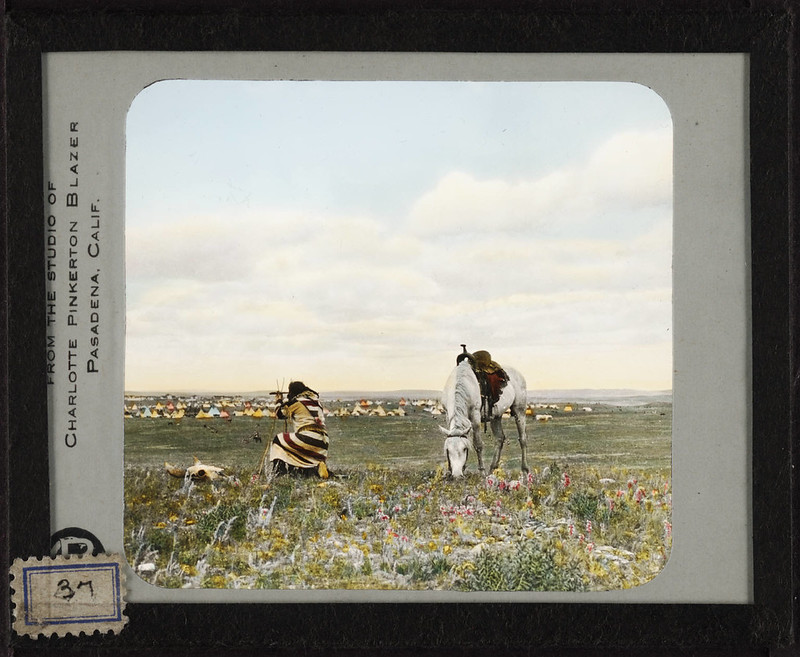

Elouise was a member of the Blackfeet Indian Tribe, and helped establish the first Native American bank there. “[Tribal camp of the Blackfeet Indians with Indian scout (Little Blackfeet?) in the foreground]. 37” by Beineke Library is licensed under CC BY 2.0.

As many of us have seen on the news in the recent past, the Dakota Access Pipeline has been met with much criticism from both native and non-native opposers. It has the potential to not only wreak havoc on the livelihoods of the Standing Rock Sioux, but also the environmental implications of introducing yet another way to continue our dependence on nonrenewable energy have ignited demonstration after protest. The pipeline threatened waterways that the Sioux depend on. If this pipeline were to be damaged or burst, it would render the waterways undrinkable and unusable to the surrounding community. Another issue was that the pipeline would run through historical native burial grounds, which is yet another reminder to the native people that the government does not keep its promises. During President Trump's term in office, it looked as if the treaties made with the Standing Rock Sioux would be broken by executive order. However, when President Biden was elected he eliminated that executive order, not only honoring the treaty with the Standing Rock Sioux but setting a precedent that Native Americans deserve more than the United States has given them for reparations in the past.4 This is the attitude we need in all of our lawmakers and government representatives. This is the example that we need to set for our future generations.

One of the many protests that occurred during this cultural and environmental crisis. “Pipeline protest” by Victoria Pickering is licensed under CC BY-NC-ND 2.0.

We often have so much interest in the injustices of our Native community (or any marginalized community for that matter) when there is a big story being covered, but this mistreatment is happening every day. Native People and Voices are important to our future, because they know this land: its intricacies and particularities. The more we support this land’s original people, the closer we will get to learning how to save the land they’ve cared for for thousands of years. We owe it to them as well, since colonizing the land has only brought environmental turmoil, sickness, cultural assimilation, genocide, and maltreatment.

References

- Bureau of Indian Affairs. (2021). Bureau of Indian Affairs (BIA) | Indian Affairs. U.S. Department of the Interior. https://www.bia.gov/bia

- Sharon, S., Gratz, Irwin. (2021, July 1). Maine’s Tribal Leaders Criticize Gov. Mills After She Vetoes Casino Bill. . Maine Public. https://www.mainepublic.org/politics/2021-07-01/maines-tribal-leaders-criticize-gov-mills-after-she-vetoes-casino-bill

- Gingold, D. M., Pearl, A. (2015, June). Tribute to Elouise Cobell. Public Land & Resources Law Review. https://cobellscholar.org/wp-content/uploads/2015/11/In-Memoriam_A-Tribute-to-Elouise-Cobell.pdf

- Native Knowledge 360º. (2018). Standing Rock Sioux and Dakota Access Pipeline | Teacher Resource. National Museum of the American Indian https://americanindian.si.edu/nk360/plains-treaties/dapl

About the author

Nicole Holmes

Nicole is a first year master’s student in the Environment & Society Foundation of the MEES program. Her research will focus on the evaluation of Environmental Restoration Projects with a focus on their longevity, efficacy, and impact on surrounding stakeholders. She enjoys relaxing outside in her hammock, reading graphic novels, and recreational mounted archery with her horse, Faith.

Next Post > Facilitating a Great Barrier Reef partnership workshop in Brisbane

Comments

-

Bill Dennison 4 years ago

Nicole,

Your blog about native Americans is personal, passionate and interesting. I recently read a book "Killers of the Flower Moon: The Osage Murders and the Birth of the FBI" which chronicles the horrific story of the Osage native Americans in Oklahoma because they uniquely maintained their mineral rights beneath their reservation--thus making them targets of greedy people once oil was discovered. The Keystone pipeline controversy that you highlighted is yet another conflict between native peoples and oil. It seems that we have some chronic issues regarding native Americans and the insatiable quest for fossil fuels. I always like the use of cultural references (in your case, a Disney film), and the images you selected are quite powerful. Interesting title, reminiscent of Donald Rumsfeld's "Unknown unknowns". Bill -

Nicholas Dawson 4 years ago

Nicole,

I thoroughly enjoyed your blog. I liked how you drew from your own personal life to write about a topic that your clearly passionate about. Truthfully, the Dakota Access Pipeline is more or less of my modern knowledge in regards to the marginalization of native american tribes here in America. So, reading your blog has made me want to do more in depth research on this topic. I enjoyed learning about Elouise Cobell and her quest to right the wrongs the American government has created. This blog gave insight on how american modern society is still lacking on understanding and acknowledging perspectives of the individuals who lived on this land long before they colonized it. Though it seems, we are starting make strides in the right direction, I believe we as whole have some work to do. -

Yanyu Wang 4 years ago

Nicole, thanks for your great blog! You provided multiple examples and also your personal experience regarding the injustice that native communities are encountering currently. I agree with the point that the general public might be interested in a big story uncovered by media or news, and gradually forget and fade out from their lives if they "feel" things have nothing to do with themselves. It is important to help establish the emotional connection for people with native communities and feel their losses in various ways to understand the holistic perspective we should view as humans and the environment. Even though we also see progress are occurring in acknowledging the rights of indigenous people own in resources and land aspects, this trend still needs to be expanded to more areas globally. At the same time, some regulations need more strict enforcement.

-

Jana Kopelent-Rehak 4 years ago

Nicole, you reminded me of many other cases known from history and anthropology. When I was in Graduate school I took a course in Politics of Archeology where we discussed the repatriation act and related trials. When visiting British Columbia Museum in Vancouver, there I found an interesting new display of the Ritual masks and artifacts. First Nation people had to sell their family objects for very little at some point when needing money for basic needs. Now, BC Anthropology Museum lets the family (mask belongs to) display, along with each mask, photographs, and the story about having let go of this secret object. I found this exhibit and its meaning to be a powerful form of repatriation and reminder. It made it alive and dynamic history rather than a dead archive. Your blog made me think about The incident in Oglala - the story about John Peltier who was sentenced to the prisoner for the incident with FBI agent on the reservation - so many of these stories, in addition to boarding schools for children to re-educate and make them be " proper " citizens resulted in alienation from home or illness and death. Sherman Alexy, writer, and comedian who wrote the script for the film Smoke Signal, expressed so well what it means to grow up on the reservation and travel between. Also, you may be interested to read Vine Deloria - classic work about Native American History. Then political internal fragmentation within tribal members is difficult to discuss as well, just like conflicted ways of being when Pueblo people had to work in uranium mining in New Mexico. Sad stories about suffering.

-

Shuyu Jin 4 years ago

Hi Nicole, I liked how you started the blog, starting with "Pocahontas", which quickly caught this blog's tone and theme for many readers. Besides, it is an excellent complement to last week's reading, whether the Zafimaniry community, living in the highlands of Madagascar; the Nuer, dancing with the cattle. I think these stories focus more or less on the crisis that indigenous peoples are going through right now. These crises are the natural survival crisis of their own ethnic and tribal reproduction and the conflict of interests with exterior communities. How to fight? I think respect for each other is essential.

-

Barry Bowman 4 years ago

Nicole, your experiences with this topic provides a strong, personal foundation for your argument for the inclusion of Native Voices in management, policy, as well as the environment. While I see plenty of depictions of Native Americans in sports and other entertainment media, I very rarely see depictions of Native Americans as morally just environmental stewards (even less so are names of specific nations used). I like how your blog presented your experiences in the context of the readings. Many parallels can be drawn between the cultural knowledge of the Maasai people in Tanzania and the Native American nations in North America. I agree that the Native Peoples should have a greater, sovereign Voice in their lives and in the relationships between humans and the environment. Your personal experience with this topic, combined with your description of recent events resulted in a very interesting perspective!

(plus I didn’t know you practice archery too!)

-

Matthew Kusche 4 years ago

Nicole,

I really love your overall topic and how you tie in your personal experiences into it. I believe strongly with your sentiments that we should put more of emphasis on this subject. I really loved how you referenced the Dakota access pipeline as within reading your first few sentences, my mind had already shot to thinking of this matter. Overall, I think you did a really great job of catching the readers attention and really backing up your position with some great information!

-

Imani Black 4 years ago

Wow. I really loved this and learning about you & your family. Indigenous/aboriginal groups and their culture are not well honored or represented the way that they should have been or need to be. In elementary school for Thanksgiving we would have "settlers and Indians day" to show us our harmonizes that time was and I loved Pocahontas so much when I was little but it wasn't until I was much older that I learned the real story of those accounts. Truly heartbreaking how we are miseducated about communities that have been historically destroyed and still are facing many obstacles. Thank you for shedding light on the correct history and honoring your tribe and many people within that heritage.

-

Jana Kopelent-Rehak 4 years ago

Nicole, I saw this short history on Archeology's Facebook page and so I am sharing it with you and the class. I have some visual materials as well. My Archeology friend, Katharine Fernstrom from Towson U. has some direct contacts with local indig. groups if you are interested.

The Chesapeake Bay gains its name from the Chesepiuc chiefdom which lived at its southern entrance. Their main town of Skicoac was on the Elizabeth River. Their other towns, Apasus and Chesepiuc, were along the Lynnhaven River. A group of Roanoke Colonists stayed with the Chesepiuc at Skicoac over the winter of 1585-1586. Relations were friendly and their chief extended an offer for the entire Colony to resettle in his territory. The Colonists politely declined and headed back to Roanoke. In a 1590 map by John White the bay is labelled as “Chesapiooc Sinus” – or “Chesepiuc Gulf”. It was used again in John Smith’s maps and the name has stuck since.

The Chesepiuc were enemies of the Powhatan Chiefom. Around 1607, Powhatan warriors attacked the Chesepiuc and killed “all the inhabitants, the weroance and his subjects”. John Smith visited the area in 1608 and reported finding Skicoac intact but deserted. The land was then resettled by tribes loyal to Powhatan who would in turn be pushed out by English Colonists.

Many speculate that when the “Lost Colony” disappeared, they had left to live with the Chesepiuc. Jamestown Colonists assumed at the time that Powhatan had exterminated the Chesepiuc because Roanoke colonists had been living with them.

In April of 1997, the remains of 64 people were discovered at the former town site of Chesepiuc. They were ceremonially reburied by the Nansemond Tribe in the nearby First Landing State Park where they can be respectfully visited today.