New York Harbor water quality

Bill Dennison · | Applying Science | Learning Science | 2 commentsOn 12 January 2017, I visited Beau Ranheim, the Section Chief of Marine Sciences, New York City Department of Environmental Protection. Beau was a graduate student in the Ed Carpenter/Doug Capone laboratory at Stony Brook University when I was a postdoc in the same laboratory. After Beau finished his Master's program at Stony Brook, he has been working for the New York City Department of Environmental Protection. It is ironic to have someone named Beau who is originally from rural Louisiana with his southern drawl working in the Big Apple, surrounded by fast talking New Yorkers. Beau has been responsible for a water quality sampling program for New York Harbor, which was the reason for my visit. As part of the Billion Oyster Program - Curriculum and Enterprise for Restoration Science (BOP-CCERS) project that the

Beau's office is located at the Newtown Creek Wastewater Treatment Plant, which is the largest wastewater treatment facility in New York City, serving approximately one million people, including lower Manhattan. It is located in Brooklyn, adjacent to Newtown Creek, which extends from the East River for 3.5 miles into highly populated neighborhoods. The channelized Newtown Creek has been heavily industrialized since the nineteenth century. In fact, the first Vaseline refinery was in Newtown Creek, as well as a large Standard Oil refinery. Newtown Creek was designated as a Superfund site in 2010.

Over the years, I have visited many sewage treatment plants and I found the Newtown Wastewater Treatment to be quite surprising in several ways. First, there were no circular water tanks. Most sewage treatment plants I have visited have large circular tanks for both primary and secondary treatment. The Newtown facility is on a limited footprint, surrounded by intense residential and commercial development, so rectangular tanks allow more intensely spaced tanks. Second, I never saw the thousands of gallons of water coursing through the plant. All the tanks were covered, reducing the odors the emanate from sewage tainted water, and this plant was the least smelly facility I have ever visited. Third, the Newtown facility has created a public park, the quarter-mile Newtown Creek Waterfront Nature Walk with its unique architectural features, plantings and environmental sculpture, as well as stunning views of New York City and the nearby industrial landscape, encouraging people to visit the creek immediately adjacent to the facility. Most other plants are hidden away and people are not encouraged to come anywhere near the facility.

New York City began treating wastewater in the late 1880s and water quality monitoring began early in the twentieth century. Beau explained that the members of the Metropolitan Sewerage Commission used to collect samples at a limited number of sites using rowboats. The NYC DEP now operates a research vessel, the Osprey, to collect water quality samples throughout the waterways of New York Harbor. The Osprey is moored in Newtown Creek, and it was nice to see the vessel that is used to collect the data I am beginning to analyze.

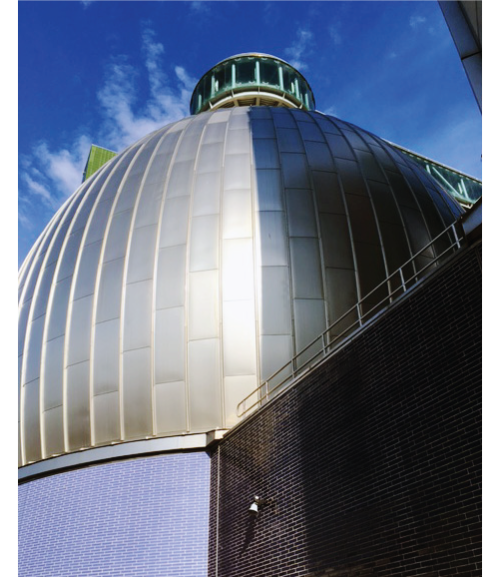

The Newtown Creek Sewage Treatment is a primary and secondary treatment facility, which means that the solids and floatables are removed in the primary tanks and then aerobic microbial degradation of organic matter occurs in the secondary tanks. The final step is chlorination before release into Newtown Creek. The sludge produced in the primary and secondary tanks is digested in giant silver egg-shaped digestion tanks, using anaerobic microbes. The digester tanks are very tall and at night illuminated with blue light, making them a local landmark. The large amount of methane produced in the digesters is used to generate power for the New York City power grid.

The big difference between New York City's sewage treatment and the sewage treatment for Chesapeake Bay is that most sewage treatment for Chesapeake has an additional, tertiary treatment process. This added treatment, known as enhanced nutrient removal (ENR), typically reduces the nutrient levels to < 3 mg/L total nitrogen and < 0.3 mg/L total phosphorus. Standard secondary treatment, also known as biological nutrient removal (BNR), results in discharge levels of 8-10 mg/L total nitrogen and 1-3 mg/L total phosphorus. New York City relies on BNR treatment and the tidal flushing to reduce the impact of discharged nutrients on water quality. The lack of tidal flushing in Chesapeake Bay makes the bay more susceptible to nutrient impacts and thus the ENR treatment.

While a sewage treatment plant is not a typical tourist destination for visitors to New York City, it was quite a unique experience and it was nice of Beau to show me this undiscovered part of the Big Apple.

About the author

Bill Dennison

Dr. Bill Dennison is a Professor of Marine Science and Vice President for Science Application at the University of Maryland Center for Environmental Science.

Next Post > Developing scientific stories for Chesapeake Bay submerged aquatic vegetation

Comments

-

envoi de MMS en nombre 9 years ago

Hi there, I wish for to subscribe for this blog to take most reecent updates,

thus where can i do it please assist. -

Suzanne Spitzer 9 years ago

If you are viewing a blog, along the left side of the page there is a blue word "subscribe" with a small envelope. Please click that to sign up!