Science, communication, and story-telling for social change

Bill Nuttle · | Science Communication |Last weekend I attended a workshop that gave me a different perspective on communicating through story telling and on the stories that scientists tell among ourselves. The workshop was Building Skills for Change put on by the Institute for Change Leaders. Olivia Chow, who led the workshop, is well-known in Canada for her work in municipal and national politics. Currently, she is a professor in the School of Social Work at Ryerson University where the institute is located.

The first day of the workshop presented the basics of story-telling. I was already aware of the importance of story-telling in science communication, being a fan of Randy Olson’s work to improve the communication skills of scientists. Allowing for some change in emphasis, what I heard before the break could have come straight out of Olson’s latest book, Houston – We Have a Narrative. People communicate mainly through stories. A story comes alive when something out of the ordinary happens.

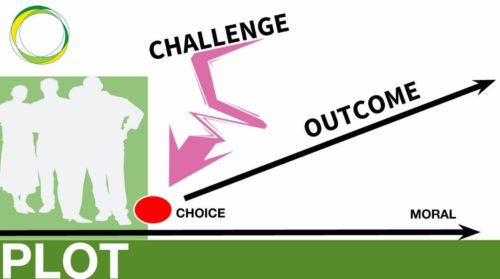

Story-telling is one of the main tools for leaders of social change movements. Leaders must learn how to craft a public narrative, a narrative that both describes what they are trying to do and recruits and motivates participants. The stories used by leaders of social change focus on people being confronted by a challenge, which requires them to make a choice, and on the consequences of making that choice.

After the break, the discussion turned to the subject of how to provide stories with emotional content. Leaders of social change use stories to organize and motivate people to take action by accessing their emotions. The approach presented for doing this follows the ideas developed by Marshall Ganz based on his experience working with Cesar Chavez to organize migrant farm workers in California in the 1960s . Ganz summarizes his ideas in this essay [pdf].

Talking about building emotional content into stories was thrilling, but it was also a little menacing. Stories have power. They sell Hollywood movies, and they can determine the outcome of elections. This power comes from their emotional content. I felt as if I was being given a glimpse into story-telling’s darkside, and my belief in the value of rational argument was shaken.

In science communications, we talk about using stories to get out of our heads and reach a wider audience through the emotional centers in the heart and the gut. But, the stories scientists tell tend to regard the world from an intellectual perspective. The And-But-Therefore narrative template derives from the classic structure of an academic discourse – thesis, but antithesis; therefore synthesis. Therefore, even when we succeed in reaching people through their heart or gut, our stories still speak to their rational mind.

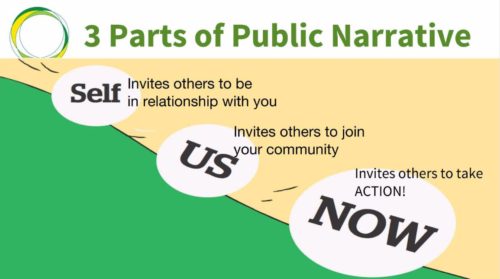

By contrast, the stories used by leaders of social change speak to people directly on an emotional level, and they also convey a lesson. Leaders use stories to rehearse people in the decisions they make intuitively, based on empathy and emotion and without conscious rational deliberation. Malcolm Gladwell calls this our instinctive intelligence, in his book “Blink.” The workshop taught us how to build the public narrative using three types of stories. The story of “Self” identifies values that motivate and guide one’s actions. The story of “Us” identifies values shared by the group. The story of “Now” identifies a threat to shared values of the group that demands action.

My first reaction was that science communication would never use the Self-Us-Now narrative framework. The subjective notions of “self” and “us” and unquantifiable humanist values are fundamentally opposed to science’s use of data and rational analysis to pursue objective truth. But, on second thought I am now willing to bet that scientists tell Self-Us-Now stories all the time.

Science is a social activity. And, like everyone else, scientists rely on our instinctive intelligence for most of the decisions we make every day. What distinguishes scientists from most other people is that the instinctive intelligence of scientists has been trained through education in science and practical experience conducting research. If we look at the way that scientists learn the values that define the scientific community and that motivate and guide the practice of science, then that’s where we will find scientists using stories of Self, Us and Now. Welcome to the dark arts.