Science for science, for environment, or society?: The role of science in environmental management

Alterra Sanchez, Stephanie Barletta · | Science Communication | Applying Science | 10 commentsAlterra Sanchez and Stephanie Barletta

Environmental management is much more than using science to solve a problem, if only it were that easy! If a lake is becoming eutrophic because of nutrient input due to nearby farming, the answer would be to not allow the farmers to use as much fertilizer; easy, problem solved, right? Unfortunately, no. The farmers might already be using the minimum amount of fertilizer, or they might not care (or understand) and as an environmental manager you cannot order the farmers to change.

Environmental management is a complex conglomeration of science, politics, economics, sociology, and psychology. This is because by managing the environment, you are attempting to manage what people do in the environment. Then, environmental management is not exclusively a science, science is just one of the main tools used by managers. So, what is the role of science in environmental management? Are scientists merely the supplier of data or should they take part in the actual “managing?”

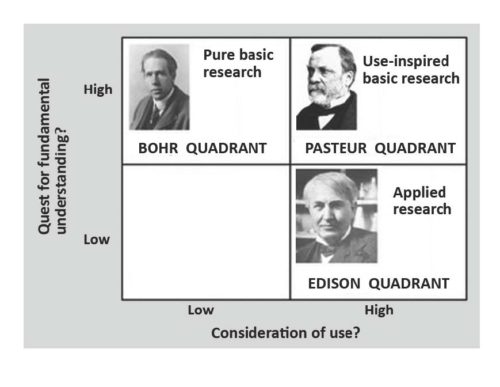

Before we can answer that question, I think we have to define what science is, or rather the point of science. Most people would agree that science can be useful (like helping to restore a lake), but whether the point of science is to be useful is a more contentious topic. According to Donald Stokes there are three types of research, which can be visualized by Pasteur’s Quadrant1. Research that is about discovery (or “a quest for fundamental understanding” about the universe) with little application is in Bohr’s Quadrant; named after the famous physicist Neils Bohr who studied quantum theory. Bohr's Quadrant research is also called ‘basic research’ or ‘pure science.’ Basic research that has some use or can eventually be applied for a use is in Pasteur’s Quadrant; named after Louis Pasteur who demonstrated that fermentation was caused by bacteria, which led to discoveries about vaccination. Finally, research that is not at all about unraveling the mysteries of the universe, but about using the information for a specific application is in Edison’s Quadrant; named after Thomas Edison who invented the electric light bulb and was more of a businessman-inventor than a scientist.

If science is done just for the sake of science (Bohr), then scientists have no place in management and are simply data-creators. If the research is designed, for example, to figure out how lake trout respond to eutrophication (Edison), than the scientists would need a place among management. They alone would have the knowledge/understanding of the system to adequately explain to farmers how and why the trout are being effected by nutrient runoff, and help decision-makers make new policies. However, it’s not always that simple, like with Pasteur, sometimes research creates unintended ‘useful’ information. Are researchers obligated to share these results with politicians and the public? Or is depositing this information into scholarly journals, where decision-makers could find the information if they needed, enough?

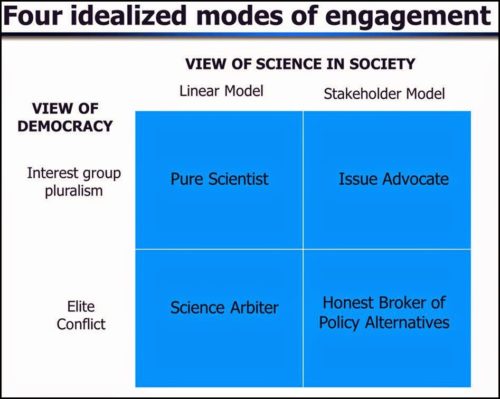

In everyday-practice, environmental management is not really about the science: it’s about being able to continue using a resource (that has value to someone), while also not interfering with anyone’s life/business/religious practices by managing this resource. The science, then, might not agree with a politician’s world view, or a community’s cultural practices, or they simply might not care. Should scientists try to explain why science is instrumental in helping the environment? Well, there are four ways of responding, and in everyday-practice they are not always distinct, but they are the Four Idealized Modes of Engagement.

Pure scientists are like Bohr, have no interest in the utility of their research and have no connection to politics2. A science arbiter is also not connected to policy and does not wish to become involved in creating policy, but understands that decision-makers might need clarification from experts2. The issue advocate, however, has an agenda and is trying to effect policy change through science; they are engaged in policy making2. Finally, there is the honest broker. Like the issue advocate they are active in the decision making process, however they are not trying to advance a particular stand on an issue2. The goal of the honest broker, instead, is to expand the number of options the decision-maker has of the science. An important distinction here is that though the honest broker does not have a specific agenda, they do want the decision-maker to have as much knowledge as possible, and to use scientific knowledge to create policy, regardless of the action taken.

It might seem to some that an honest broker, and especially an issue advocate, isn’t doing science at that point, but playing politics. Even the honest broker, though they are offering “all of the facts,” still has to try to get the decision-maker (or the public) to care about science in general before they will listen. How do you get them to care? Usually through things that they are interested in, they care about, or will make them money. If you are trying to get someone to listen through their emotions or monetarily, is being an honest broker possible? Through the process of getting them to “care” about science, can you objectively present “all of the facts?” This where the concept of stealth issue advocacy comes in. A stealth issue advocate claims to be “only about the science,” but really has an agenda2. Sometimes, however, they might not even be aware that they are a stealth issue advocate as they seek to try and get decision-makers and the public to understand, and care, about the science involved with their issue.

Environmental management is a socio-economic problem, not just a scientific one. That, however, is the point: in reality science plays but one role in the management of natural systems, but it is vital. Science provides the data to make informed decisions. How and if the uninformed become informed, is, unfortunately, a question for the decision-maker and the scientist.

References:

1. Stokes, D. E. (1997). Pasteur's quadrant: Basic science and technological innovation. Brookings Institution Press.

2. Pielke Jr, R. A. (2007). The honest broker: making sense of science in policy and politics. Cambridge University Press.

Next Post > The Chesapeake Sentinels

Comments

-

Hadley McIntosh 9 years ago

Something else to consider is that scientists are at different times the four modes of engagement. Projects develop and new projects are started, while the interests of scientists, the community-at-large, and policy makers change. We, as scientists, just have to be aware of which way we are interacting with society or which "hat" we are wearing when discussing or presenting data on a socially relevant issue and understand how that will be perceived.

-

Juliet Nagel 9 years ago

Effective communication of science has always been a challenge. As Alterra said, should scientists present all the facts, or just those they deem important to a policy maker's decision? Policy makers typically don't have the time or inclination to read scientific papers, nor may they be interested in the nuances of the research. They want to know the main finding of a study and how it applies, but often research isn't that easy to distill. Getting people to "care about science" to me seems less of an issue than getting them to understand what the science means, and how it affects them.

-

Kavya Pradhan 9 years ago

I think the comment in the last paragraph about science's role in "making informed decisions" is a key point and as scientists engaged in environmental management I don't think we can shy away from some level of advocacy simply by virtue of what we study. Additionally, I wonder if there is something to be learned from scientists who clearly understand the science behind environmental issues, but do not take a stand or are not involved in environmentally inclined efforts. We often talk about making the public aware of the science behind environmental issues, but I know a few folks who would understand the science without a problem, but this does not lead them to action.

-

Annie Carew 9 years ago

I really enjoyed the breakdown of "types" of science. That's not something I've seen or heard a lot about, and I thought it was a helpful visualization, especially if readers of this blog are not necessarily science people.

I'd like to second Jake's comment about the ambiguity of "stealth issue advocacy." I don't think it's possible for scientists to be completely impartial, even if our data is unbiased.

-

Katie Martin 9 years ago

I like that you connected Pasteur's quadrant in the "Three Types of Scientific Research" to scientific data availability. Open access and better data management is a really important discussion. Databases from federally funded research are frequently not maintained and often research relevant to certain groups is only accessible those with academic subscriptions.

-

Stephanie 9 years ago

This is an excellent post that both highlights and exemplifies the various roles scientists can have in relation to management policy. It also does a great job of discussing the conflict between researcher and scientists on an issue. As beginner scientists ourselves, I think that communication by us and communication with stakeholders and policy makers will be one of the most influential aspects of our future. This post does a great job outlining and explaining the situations we may face or find ourselves caught up in.

-

Dylan Taillie 9 years ago

Thanks for the great blog and comprehensive summary of the content we looked at last week! I agree with Jake in the sense that a stealth issue advocate could just be someone who simply doesn't have enough experience in other fields to be a true issue advocate. We talked about our politicians not being 'career politicians' and having science backgrounds, and I wonder if scientists should do the same and not be 'career scientists' (if that parallel holds up). Should scientists possibly be trained more in the social sciences? Take more science for environmental management classes, perhaps?

-

Ana Sosa 9 years ago

Theoretically, everybody should be invested in environmental management, even if it's just for their own community or ecosystem. Everybody is a stakeholder inevitably, how can we as scientists communicate this and make everybody invested without sounding threatening or fatalistic?

-

Jake Shaner 9 years ago

Blog did an excellent job of concisely highlighting the main roles of scientists in management. The concept of the "stealth issue advocate" still bugs me a bit. I feel like Pielke and others make the concept sound very cut and dry but to me it seems like to a point we are all issue advocates at times, some more than others. Maybe it is due to the compartmentalization of science, i.e. someone who has studied a specific species or process is going to know more about it and possibly care more about it, but wouldn't be able to provide as much insight on other aspects (economic, health etc...) of an environmental issue to give a truly honest and comprehensive report to a politician or manager.

-

Ginni La Rosa 9 years ago

Both Pasteur's Quadrant and the Modes of Engagement diagrams offer enlightening insight into the various internal motives of scientists and perhaps of science itself. They show that there can even be conflicts among scientists regarding how information should be presented and/or shared. Another related topic for future discussion could be that of accessibility to scientific information through journals or other publications. Are scientists (or science in general) considered secretive or inaccessible due in part to the information being difficult to reach and/or translate to layman's terms? How can we as scientists ensure that information needed for management is available to stakeholders in a form that is both thorough and understandable?