Scientists in Media: “Give me a microphone, and I shall waken the world”

Wenfei Ni, Martina Gonzalez Mateur, Stephanie Siemek · | Science Communication | 4 commentsWenfei Ni, Martina Gonzalez Mateu, Stephanie Siemek

Taking a last glance of the materials on the table, Rona Kobell from the Bay Journal adjusted her glasses, and asked clearly, “Why is anyone still fishing in the Anacostia River anyway if it is very polluted?

“It is because lots of urban families nearby just go fishing there for relaxation. And my research actually focuses on the algal bloom and nitrogen pollution there”, carefully answered Melanie Jackson from Horns Point Lab.

“What does the pollution in Anacostia have to do with the Chesapeake Bay?" Rona added.

“The Anacostia River travels through the urban area then goes into the Potomac River, and finally to the Chesapeake Bay ."

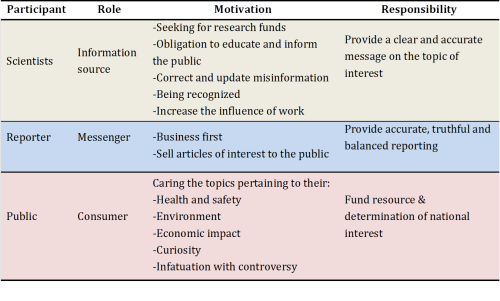

Of course, the conversation above will not appear on the headlines of Washington Post, but this is a vivid scene about how science is communicating with the media. In this process, the knowledge goes through a complete information chain from scientists to the public. The media acts as a messenger to convey the information and the public is the consumer. Each participant in this process has a unique identity and is driven by different motivations (Table 1, Herbert O. Funsten, 2003).

Scientists have always been imagined as a bunch of people trapped in a cold laboratory studying and seeking the answers to the questions that intrigue them. They are merely “learning for the sake of learning”. However, scientists started to realize that what they were studying was changing – not always in a better way. For environmental researchers in particular, they were often among the first to find the early signs when things were not what they were supposed to be. At some point, their focus of study might have switched from understanding the natural aspects of a species or physical phenomenon, to investigating changes that are a cause for concern. With that came a desire to voice their views about questions like, “what are the reasons for the unfortunate change?” or “what are the potential risks for human beings and are there any possible solutions?” The scientists found themselves reaching outside the laboratory to engage the public on environmental issues. They felt oblige to convey a clear message, providing accurate and balanced perspectives on their scientific findings. The stakeholders, such as the public and policy-makers, are alerted of the importance of the issue, and then are able to make informed decisions based on scientific evidence. In the case of the Chesapeake Bay, environmental problems, like water quality degradation and fishery production decline, are being well-studied by scientists, and thus public attention and awareness on these issues has been greatly raised. Communicating science is not only important to the outside world, but it can also improve the scientist’s stature and reputation among peers, and help with research funding and career development.

Media are always looking for stories of importance to readers, which connects to their lives and interests. Television, radio, and local/national newspapers are some of the most popular news media for communication. Each of them has its own merit and limitations. Since social media has been emerging as a new power owing to the fast development of the internet, the scientists play the roles of both information source and messenger. One merit of using social media like blogs, forums, or twitter to deliver scientific information, is being able to communicate with people in real-time and getting feedback from each other. It can involve both professional collaborations and communication with the public. The risk of messages being misinterpreted is lowered to the minimum in this way because scientists themselves can convey their messages without relying on journalists or reporters to interpret their ideas. More importantly, exhibiting the detail of research to the public, no matter the process or result, will make science easier to accept and strike a chord.

When considering traditional media, the main responsibility of a reporter is to obtain information from scientists and communicate it to the public. They should digest the message in a way that connects the scientists’ intention and the social concerns, then translate it from scientific/academic language to everyday language. However, usually the journalists or reporters are not experts in scientific fields. Sometimes it is hard for them to explain a complicated concept in a short time. In addition, reporters have a great desire to get the attractive story first to scoop the competition among peers. They might sacrifice the accuracy for expediency running contrary to the rigorous nature of science. The story may air without any valuable scientific message presented or with only very little information within the headline.

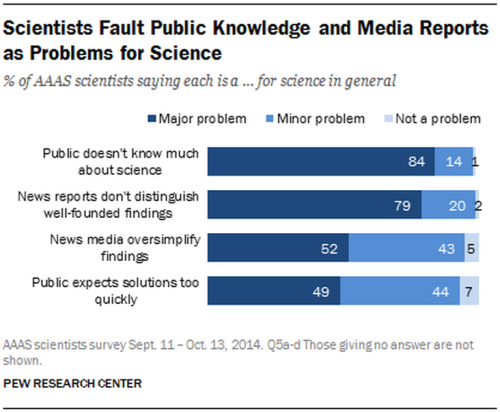

The public and policy makers believe that communication is an obligation for scientists, however, not everyone feels that scientists have done a good job in engaging with the media. Findings from a survey by the Pew Research Center in collaboration with the American Association for the Advancement of Science (AAAS), show that only 51% of AAAS members chose to talk to reporters.

79% of the AAAS scientists consider communication to be hampered because the news reporters don’t distinguish well-founded findings. And 52% thought the over-simplification of reports was a major problem for science. It indicates that media needs to develop an efficient way to overcome these queries from scientists; scientists, on the other side, need to take responsibility to share their research with the public through the media.

When looking at our mock interview, some simple yet quite practical tips could be summarized as inspiration.

“Why are there fewer farmers enrolling in the program?”

“What do you think are the economic factors that prevent them from signing up again?”

“What are the strategies to get more enrolments?”

For the media:

- Asking detailed and progressive questions like the ones above is always an effective way not only to guide the interviewee in organizing their points, but also to provide a frame to the audiences to figure out the key issue.

- Reporters should attempt to provide balance to the scientific story to ensure fairness to opposing sides. However, sometimes it is equally important to focus on the broad picture and find common ground when there are two differing points of view.

- Always be prepared with certain scientific background before an interview, and at least be familiar with the most relevant academic articles.

For the scientists:

- Answering the question “so what?” for the potential audience is the starting point. Package the research to resonate with specific segments of the public.

- Use a message box to organize the information and focus on the few key messages that are most relevant for the audience.

- Write a story, keep it simple and clear, especially for audiences with no scientific background.

- Make the message memorable, even though certain information may be lost. Use metaphors to convey complex ideas in an easy and understandable way, especially in the headline.

- Be concise. Do not use jargon, or long and complex phrases.

- Be enthusiastic. Project yourself enthusiastically during the interview, and when possible use your own life experience to make the reporter excited about both the message and the opportunity to interact with you.

- The story should not only discuss the science itself but also, its moral and ethical implications. The topic of climate change is a good example.

In short, it doesn't matter how right you are if nobody is listening to you. The most important thing is to choose to inform the audience outside your research arena, those who can make real changes happen, by the voice of media.

References:

- Nancy Baron, 2010. Escape from the ivory tower: A guide to making your science matter.

- Herbert O. Funsten, 2003. You and the media: A researcher’s guide for dealing successfully with the news media [pdf]

- Victoria Murphy, How can scientists better communicate with the public.

- Alison Bert,2014. How to use social media for science-3views.

Next Post > Developing a constitution for Chesapeake Bay

Comments

-

Whitney Hoot 11 years ago

The authors point out that strong, clear communication is not only important in terms of conveying science to the media and the general public, but also vital for obtaining funding in many cases, as the "broader impacts" of research are a significant aspect of many grant applications. If no one knows about your science, how broad can the impacts possibly be? It seems that science communication can put one grant application above the rest in a stack of qualified applicants. Scientists should be asking the "so what" question before, during, and after conducting research. Another good question to ask is HOW can we make the message memorable - as Wenfei said - and HOW can we deliver it? Multi-media productions, especially videos and podcasts, are a great way that scientists can produce and publish their findings to make them accessible to a general audience.

I was in Costa Rica over winter break for a graduate field ecology course that included a science communication workshop. One of our assignments was to create a 1-minute elevator speech to explain our research to the general public. We were challenged to avoid all jargon. Well, this turned out to be more difficult than I expected. After I recited what I thought was a concise, clear elevator speech, my professor said, "Nope. You can't say "plant community" - most people do not know what a community is in that context." Even common words - like community or the dreaded "uncertainty" - can mean something totally different to scientists and non-scientists. When preparing something aimed at a general audience - like a speech, presentation, or interview response - it's a great idea to practice your talk in front of a friend or family member who isn't connected to the scientific world. Otherwise, it's easy to miss nondescript jargon that can be misunderstood.

-

Rebeca Peters 11 years ago

I really liked the way to began the blog with an example of some the questions and answers we did in class with the mock interviews. Also the tips at the end of the blog are good. I think it is important for scientists to remember that they are speaking to the general public who may not understand complex scientific jargon so scientists need to work on begin able to explain their research in simpler ways.

-

Sabrina Klick 11 years ago

Wenfei did a really good job with the blog. It covers a lot of what we went over in class. I agree that the media can act as a "middle man" between scientists and the public to communicate science in a way that the public will understand. After the four interviews last class, I think interviewing and talking with the media about science is a skill that takes practice and time to develop. The unpredictability and journalist "traps" makes it more challenging when they ask about topics that we are not prepared to talk about. It is also challenging to remember to talk in quotable sentences. I agree with what Dr.Boesch said last class about having quick general explanations or definitions about topics such as climate change for those unexpected questions.

-

Michelle Lin 11 years ago

Great job! Wenfei Ni

I like your opening of the article that you visualize what was happening during the class. I think it's realy good. And, I agree that scientist have responsibilities to delivery the message out to broader audience, especially the environmental scientists . Through effective communication with general public, it helps us to re-think and re-shape our scientific questions and then engage more people to participate in environmental issues.