Solving "Wicked Problems" at the Chesapeake Studies Conference

Anna Calderón and Nick An ·This past week, on June 1st and 2nd, we had the pleasure of attending the Chesapeake Studies Conference put on by Salisbury University. Although the conference itself was small, with many of the speakers and attendees having known each other for quite some time, newcomers like us were met with open arms by this tight-knit Chesapeake scholar community. As we walked into the conference’s reception scene, we were met with the smell of delicious catered cuisine and the company of some of the region’s top experts on its ecology, culture, and history.

The front of the Patricia R. Guerrieri Academic Learning Commons Building, where the Chesapeake Studies Conference was held. Picture by Anna Calderón.

The keynote speech, given by Michael Lewis on behalf of Jerry Schubel, discussed two main themes on the Chesapeake Bay: change and continuity. He gave a brief overview of Chesapeake Bay programs and how although there has been a very slow increasing trend line, the future isn’t promising because change isn’t happening fast enough. There are many reasons why the programs have fallen short of their goals: scores of point sources, millions of non-point sources, and climate change that have all compounded together to create what is described as a “wicked problem.”

“Wicked problems,” such as climate change, are defined as seemingly unsolvable issues due to a combination of many factors such as evading clear definitions, being multi-causal, and requiring many different solutions at once. This problem requires a drastic shift from the current Chesapeake restoration paradigm, with older and current approaches no longer cutting it. The current approaches being taken within the Chesapeake Bay Program are causing a slow improvement…but this paradigm with the way it currently stands cannot be successful in helping remedy the issues it is targeting.

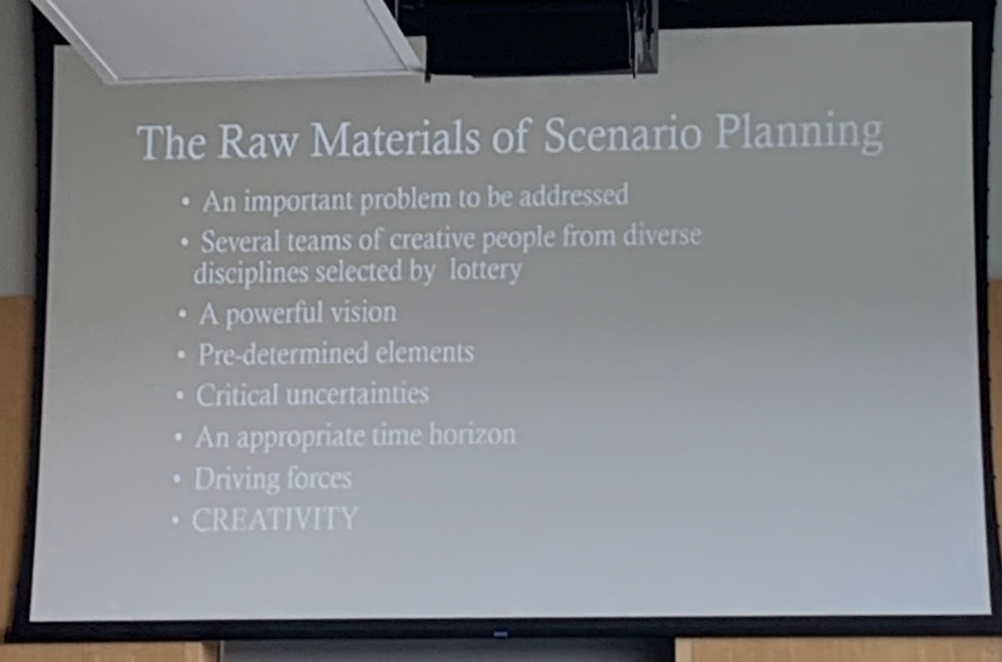

Instead, Jerry Schubel suggests embracing an uncertain future through tactics such as scenario planning. Each scenario is created in an innovative way as a story of how the future might turn out. This is not a prediction, but a method of decision-making that is informed by assumptions about the future. The goal of this approach as it applies to the Chesapeake Bay is to imagine new futures for the bay so as to form new models that can successfully tackle “wicked” problems, instead of being stuck in the past with restoration solutions that no longer apply to the scale of issues we are facing. This final message helped to set the tone for the rest of the conference with an emphasis on new ways of thinking to understand and inform solutions on solving the great challenges of the Chesapeake Bay.

A slide from Jerry Schubel’s keynote presentation on what is needed for successful scenario planning as a new approach to tackling the complex issues of the Chesapeake Bay. Picture by Anna Calderón. Picture by Anna Calderón.

Sociocultural anthropologist Emilia Guevara, a Doctoral Candidate with the University of Maryland Department of Anthropology, provided another perspective relating to the cultural rather than ecological aspects of the Chesapeake Bay. Researching how immigration alters identity and places migrant women in “precarious situations” with a lack of care, her work focuses on migrant women from Jacala de Ledezma, Mexico who work seasonally in Maryland crab houses on the Eastern Shore. Tying these two case sites together, she illustrates just how global ties to the Chesapeake Bay can be.

Illustrating her anthropological findings through the story of one of these women, Doña Lucia, Guevara unveils how deeply harmful worker visa crises and financial insecurity have been to the seasonal workers of Jacala de Ledezma, and how moments of uncertainty like this, particularly within trans-national seasonal work, lead to violence and trauma for these women. “Circuits of care”, the support networks that these women rely on amidst these uncertainties, have helped them withstand the heavy psychological cost of these uncertainties. These circuits also serve to aid these women in navigating the vast complexity and duality of their lives with this work. Emilia Guevara’s presentation brought attention to just how significant global ties to the Chesapeake Bay can be, and how important it is to platform the stories and needs of seasonal migrant workers within the area.

Emilia Guevara standing at the podium with the projector screen behind her. The slide being presented shows a picture of Doña Lucia standing in the center of her kitchen, with the slide title reading “Doña Lucia’s Story.” Picture by Anna Calderón.

William Luke Hamel, a Doctoral Candidate at the University of Virginia, advocated for a new way of analyzing rivers in the Chesapeake Bay. While the water from the rivers is a part of nature, Hamel uses urban political ecology works to describe how some of this sense of nature is lost as rivers are processed through human infrastructure systems. Therefore, rivers should be seen as connected to human systems and be viewed as malfunctioning or poorly designed human infrastructures that can be aided through preventative solutions. Rather than blaming urban issues of flooding on rivers themselves, this framework shift would place the responsibility on people. By doing so, rivers would be reshaped from a common neglected infrastructure to a precious stewarded one where people push for active solutions to fix the ailing infrastructure such as by reducing landscapes near rivers, implementing blue-green infrastructures, and limiting waterfront development.

As showcased by some of the many insightful talks at the Chesapeake Studies Conference, the solution to the “wicked problems” posited by Jerry Schubel in the conference’s keynote address seems to lie in transdisciplinary work between individuals from a vast range of backgrounds and specializations. Summits, focus groups, and other gatherings among these professionals to work on the complex issues of the Chesapeake Bay and their effects appear to be the only pathway towards real change. What do you think is the best pathway to change?

Blog written by: Anna Calderón and Nick An

Anna is a Global Sustainability Scholar and is working on the transnationally-focused COAST (Coastal Assessment for Sustainability and Transformation) project based at UMCES. Anna is passionate about addressing water scarcity, understanding hydrological systems in light of climate change, and participating in serendipitous community-based science. She is a senior at Wellesley College (Class of ‘23) majoring in Geoscience and Anthropology with a special interest in hydrogeology. Anna’s contact information is asofiacalderon5@gmail.com.

Nick An is a Global Sustainability Fellow and is working on the transnational Coastal Ocean Assessment for Sustainability and Transformation (COAST Card) project. Nick is a firm advocate for the One Health paradigm, the idea that the health of humans is intricately connected to the health of animals and the environment. Nick earned his B.S. in environmental science and anthropology from Emory University (Class of 2022). He is currently a MPH Candidate in environmental health at Emory University (Class of 2023). Nick’s contact information is nick.an@emory.edu.