Stumbling Into a New Approach

Heath Kelsey · | Science Communication |As we’ve pioneered new ways to develop ecosystem health assessments and report cards, we’ve learned a few lessons on what makes them successful and what does not. The most successful projects (those that continue on after our involvement, creating lasting impact) are those in which we’ve approached the process as a true partnership with colleagues from diverse backgrounds, areas of expertise, and perspectives.

But we didn’t just decide one day that this was the way to do it, it was a technique that we realized over time through practical experience and sometimes painfully learned lessons. To create report cards and health assessments successfully, we need to engage deeply with as many interested parties as we could. If we are seen to be representing only one sector, usually conservation or environmental causes, without concern for wider societal interests, our efforts could be met with indifference or even hostile resistance.

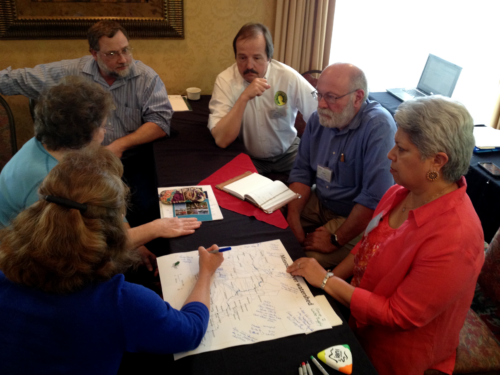

We began working with stakeholders and researchers from different types of organizations and diverse areas of expertise. Because of their varied backgrounds, they all had different perspectives and desired outcomes for the report cards. In order to work together, we had to learn each other’s respective technical languages, acronyms, and jargon. Only then could we develop a common vision for our product. Importantly, we also created a common understanding of how the system worked, and a common vision for what a healthy future system could be.

So by going through this process, we cobbled together some overarching principles that were common to the more successful projects:

- We need a balanced view of interests represented. If a project is focused narrowly (e.g., on the health of a natural system), it is less likely to be relevant to society as a whole, and less likely to be acted upon. Social, Economic, and Cultural concerns should be balanced equally with Environmental ones. For a project with real impact, this is essential.

- More diversity of opinion is good, as long as there is an understanding that 100% consensus is often impossible.

- Everyone’s opinion needs to be heard and respected. When someone’s view is acknowledged, we can often move on to consensus, but until that view is voiced, there will likely be resistance. An atmosphere of trust and respect is imperative.

- Transparency is king. If the process is unclear or opaque, it is less likely to be accepted within the group or to external audiences.

- The process should be organic. The results of the discussion within the group should form the design of the assessment, analysis methods, and important messages to be conveyed.

We used them to guide us as we formed new partnerships and did more assessments, but we felt a bit like we were operating without a net: We understood that there were some supporting principles from things like collective action or participatory appraisal [links to previous blogs], but we felt a bit like we were proposing some new and different approach, one that we kind of “made up” as we went along.

If we had only known to look up “transdisciplinary” in a literature search, we could have seen that our approach is not new, but that there are a growing number of articles that describe the process and provide direction for these types of projects. Transdisciplinary research is defined variously, but centers on the idea of multidisciplinary researchers partnering with non-scientists and stakeholders to co-design research projects, outputs and outcomes. This creates science that is relevant, credible, and legitimate (Cash et al., 2003), which in turn increases the likelihood that it is noticed and acted upon, thereby leading to measureable positive change.

We feel that the work we’re doing is well described by the transdisciplinary literature, but the perspective that we gain through reviewing this newly discovered body of work allows new insights and guidance as we go about our work. We’re happy that we’ve found an intellectual home. Discovering this allows us to benefit from the growing body of work that evaluates projects and processes (Belcher at al., 2016), and considers ways to make it more impactful (Lang et al., 2012; Roux et al., 2010). If people who are engaged in these projects know where to look, they may refine what they are doing with a bit less pain and suffering than we did.

Sources

Belcher, Brian M., Katherine E. Rasmussen, Matthew R. Kemshaw, and Deborah A. Zornes. 2016. Defining and assessing research quality in a transdisciplinary context. Research Evaluation 25(2016):1-7

Cash, David, William C. Clark, Frank Alcock, Nancy M. Dickson, Noelle Eckley, Jill Jäger. 2003. Salience, Credibility, Legitimacy and Boundaries: Linking Research, Assessment and Decision Making. John F. Kennedy School of Government Harvard UniversityFaculty Research Working Papers Series. doi:10.2139/ssrn.372280

Lang, Daniel J., Arnim Wieck, Matthias Bergman, Michael Stauffacher, Pim Martens, Peter Moll, Mark Swilling, and Christopher J. Thomas. 2012. Transdisciplinary research in sustainability science: practice, principles, and challenges. Sustainability Science (2012) 7 (Supplement 1):25-43.

Roux, Dirk J., Richard J. Stirzaker, Charles M. Breen, E.C. Lefroy, and Hamish P. Creswell. 2010. Framework for participative reflection in the accomplishment of transdisciplinary research programs. Environmental Science and Policy 13 (2010):733-741

About the author

Heath Kelsey

Heath Kelsey has been with IAN since 2009, as a Science Integrator, Program Manager, and as Director since 2019. His work focuses on helping communities become more engaged in socio-environmental decision making. He has over 15-years of experience in stakeholder engagement, environmental and public health assessment, indicator development, and science communication. He has led numerous ecosystem health and socio-environmental health report card projects globally, in Australia, India, the South Pacific, Africa, and throughout the US. Dr. Kelsey received his MSPH (2000) and PhD (2006) from The University of South Carolina Arnold School of Public Health. He is a graduate of St Mary’s College of Maryland (1988), and was a Peace Corps Volunteer in Papua New Guinea from 1995-1998.