Take off your blindfold. There’s an elephant in front of you.

Taylor Gedeon · | Applying Science | Learning Science | 9 commentsBy: Taylor Gedeon

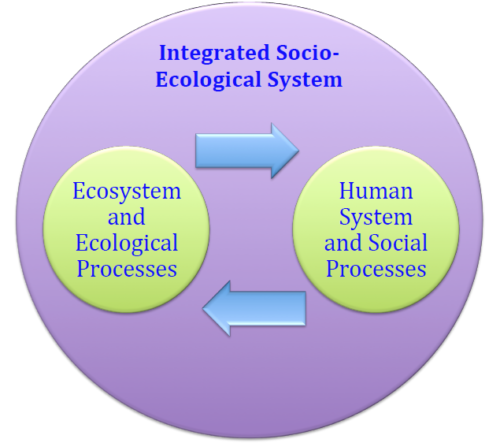

Last week, the Environment and Society class discussed the need for transdisciplinary research, which cuts across typically separate disciplines in order to solve the complex problems facing our world today. This week in class, we examined one example of such research, which is a conceptual model that attempts to link human and environmental dynamics – the socio-ecological system, or SES. This model was first introduced in 1998 by Fikret Berkes and Carl Folke in response to the typical way of presenting resilience as controlling for change, and engineering a system capable of reverting back to equilibrium. In this new way of thinking, called ecological resilience, there doesn’t need to be one stable state of a system. Instead, systems can shift back and forth between multiple desirable states and remain resilient. Thus, an SES model incorporates many different phases, adaptations, and disciplines. But how would you visualize such a complex model? To me, the SES model is an elephant. Let me explain.

There is an ancient Hindu parable about blind men and an elephant. In the story, a group of blind men who have never encountered an elephant are led to the animal and allowed to study it by touching one part of the creature. One man touches the trunk and decides it must be a snake. Another man touches the tusks and declares that they are spears. Another man feels the elephant’s ears and decides they are large fans. The men argue about the definition of the elephant because they have made a crucial mistake. They are not putting the pieces of the whole together. They are not seeing the elephant.1 When you narrow your scope, you miss the big picture.

The SES model is an elephant. An elephant is made up of many different parts – tusks, ears, a trunk, and more. The SES model also has many parts, incorporating all aspects of ecological and human environments. Elephants grow and change. So does the SES – it is a continuous, adaptive cycle.

Dr. Elizabeth R. Van Dolah, a post-doctoral researcher from the Department of Anthropology at UMD, joined our class this week to walk us through the SES model using two conceptual papers and one case study to showcase the SES approach at work. In the first paper, “Situating social change in socio-ecological systems (SES) research,” authors Muriel Cote and Andrea J. Nightingale highlight that the way ecological and human systems operate and respond to perturbations are often quite different. Ecological systems’ adaptive responses are mediated by physical shocks or perturbations. Social systems’ adaptive responses are instead mediated by politics, culture, and economics, and respond to power dynamics within the system.2

To elaborate, Dr. Van Dolah walked us through an example. Harmful algal blooms (HABs) result when there is an overabundance of nutrients in a body of water, often entering from nearby agriculture. Lake ecology responds to blooms with decreased oxygen in the water and the death of marine life. Farmers respond with concerns regarding possible increased regulations to limit the output of nutrients. Their response was not due to the harmful algal bloom itself, as they did not directly use the lake, but rather stemmed from their past experience with HABs and political, economic, and cultural concerns. In this scenario, the abstract model offered by SES over-simplifies key differences.

The SES approach is not perfect, and Dr. Van Dolah took the time to highlight some critiques. In the second reading, “Social-ecological systems, social diversity, and power insights from anthropology and political ecology” authors Michael Fabinyi, Louisa Evans, and Simon J. Foale first point out that SES assumes that people are primarily concerned with the environment. In this way, SES models have a tendency to greenwash human practices and institutions in ways that can misrepresent their social, political, or cultural function. Dr. Van Dolah pointed out the importance of considering knowledge, culture, and history in contextualizing socio-ecological dynamics. Fabinyi et al. also critiqued the SES model for oversimplifying and homogenizing social complexity, arguing that the model overemphasizes the role of institutions and social units. The authors also argue that SES resilience is too objective in defining what is a desirable state, with a tendency to overlook poverty and inequities inherent to SES. Exploitation can lead to different outcomes for different people across different scales; therefore, SES research should examine trade-offs more closely. Trade-offs include social versus ecological well-being, and well-being across temporal and spatial scales, like local versus regional, and current versus future.3

In spite of these critiques, the SES framework is useful in emphasizing the need for transdisciplinary research. There is also a need for more social science research in this area. In a step to fill this gap, Dr. Van Dolah discussed our final assigned paper for this week, which she co-authored using an SES approach. The paper was called “Marsh Migration, Climate Change, and Coastal Wetland Resilience: Human Dimensions Considerations for a Fair Path Forward” by Elizabeth R. Van Dolah, Christine D. Miller Hesed, and Michael Paolisso. As sea-level rise occurs, crucial coastal wetlands are being threatened on the Eastern Shore of Maryland. Current research focuses on the ecological realm of management strategies to protect these wetlands and model their projected movement along marsh migration corridors. However, less attention is given to the human dimensions that must be considered in managing the marsh and promoting resilience for both nature and society. To answer this need, the authors selected churches to study potential improved connectivity between rural communities and government, as churches are trusted and common in these areas. 4

In one vignette, the authors highlight how protecting individual property rights is increasingly conflicting with wetland protection, as homeowners who add soil to areas of their property that are becoming inundated are actually breaking the law. Here, the priority appears to be on the protection of the natural landscape at the expense of the individual. While this promotes resilience for the marsh, it is not resilience for the community. The elephant trunk is not a snake. There are also crucial cultural, economic, and political reasons why these communities are not able to simply sell their homes and ‘retreat’ to a new area. For many people, this land is all they have. The community is focused first on their cultural and economic realities. One classmate pointed to a quote from the paper that reads, “The church grounds also importantly symbolize the community’s historic resilience in the face of racial adversities.” 4 While many of the problems in this community extend beyond the bounds of the ecological realm, most management approaches come out of a focus on the environment.

How do we solve these complex issues? Is there a management method that benefits both the environment and the people living there? Where do we even start? We should start by looking at the entire elephant. The SES framework is not perfect, but it provides a starting place for considering all of the stakeholders of an issue. We must continuously ask ourselves the question “resilience to what and for whom?” In this way, we see the whole picture, not just a piece. Let’s make this world a better place... we should all get the chance to see the elephants.

References:

1. The Blind Men and the Elephant.(n.d.). Peace Corps.

2. Cote, M., & Nightingale, A. J. (2012). Resilience thinking meets social theory: Situating social change in socio-ecological systems (SES) research. Progress in Human Geography, 36(4), 475-489.

3. Fabinyi, M., Evans, L., & Foale, S. J. (2014). Social-ecological systems, social diversity, and power insights from anthropology and political ecology. Ecology and Society, 19(4): 28.

4. Van Dolah, E. R., Miller Hesed, C. D., Paolisso, M. (2019). Marsh Migration, Climate Change, and Coastal Wetland Resilience: Human Dimensions Considerations for a Fair Path Forward. Manuscript under review.

About the author

Taylor Gedeon

Taylor Gedeon is a second year master’s student in the University of Maryland’s Marine Estuarine Environmental Sciences program, with a concentration in Environment and Society. She works with Dr. L Jen Shaffer to study the application of a socio-ecological framework to U.S. wildlife management, attempting to increase representative stakeholder engagement and support conservation measures. Taylor is also a member of a research team supported by the Maryland Department of Natural Resources that is examining beneficial use placement occurring in marshland on the Eastern Shore.

Next Post > Making connections to ensure a clean and healthy Chesapeake Bay

Comments

-

Megan Munkacsy 6 years ago

I love the proverb example of the elephant!! So cool, and more interesting than the forest through the trees typical choice. great job!

-

Alison Thieme 6 years ago

I agree with Megan and Enid, good choice of proverb. Inequity and poverty might be the tail of the elephant, even when you look at the whole elephant, you can only see one side at a time.

-

Enid Munoz Ruiz 6 years ago

I agree. Looking at a SES frameworks is looking at the sum of parts that form the bigger picture. Great job synthesizing what was discussed in class. I really enjoyed the Hindu proverb.

-

Isabel Sullivan 6 years ago

I love the elephant like everyone else and I think it really encompasses what SES is. I think it can even be taken a step further by saying that SES sees the elephant, but does not see every elephant. Since every area is slightly different, SES helps but cannot tell us everything. I really liked this blog! It provoked much thought!

-

Michael Paolisso 6 years ago

Very clearly written and accurate and raises many of the right questions. Well done! Maybe SES is the 800 pound gorilla instead of the elephant. What might that mean? How do these metaphors help? Any cautions? Enjoyed it.

Michael -

Amanda Rockler 6 years ago

This captured last weeks reading and lecture so well. Do the feedback loops unite the smaller pieces to create the big picture? Nicely done!

-

Kayle Krieg 6 years ago

Great creative blog! Tied in very nicely with last weeks transdisciplinary discussions.

"When you narrow your scope, you miss the big picture."- this can be applied to many approaches we have discussed this year, and keeping this in mind helps (me at least) to remember to step back and look around at each scenario with a short and long lens.

-

Andrea Maria Miralles-Barboza 6 years ago

"The elephant is not a snake", creative funny and accurate blog!

-

HAMANI WILSON 6 years ago

Excellent use of graphics and well written! I love the use of the ancient Hindu parable about blind men and an elephant too.