The Chesapeake Bay and the Baltic Sea: Adapting to Changing Climates in the New World and the Old

Katie Martin, Hadley McIntosh · | Science Communication | Applying Science | 4 commentsKatie Martin and Hadley McIntosh

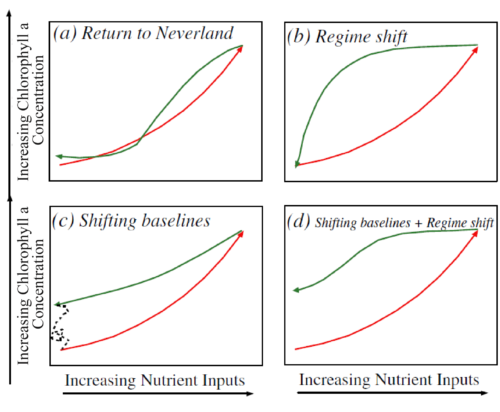

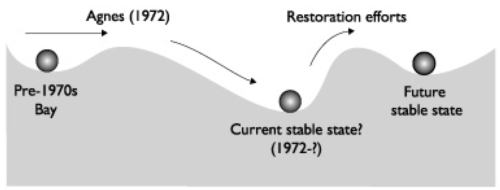

In J.M. Barrie's Peter Pan and Wendy, Neverland is a fantastical land—an escape from passing time and reality1. Is returning to the Chesapeake Bay of old with lower turbidity and nutrient levels and a seemingly unlimited oyster and crab harvest an equally unrealistic fantasy? The "Return to Neverland" scenario, coined by Duarte, Conley, Carstensen, and Sánchez-Camacho in "Return to Neverland: Shifting Baselines Affect Eutrophication Restoration Targets," is the return to a past reference state by the removal of sources of degradation—an ideal that often remains the basis for environmental legislation2. Duarte and colleagues argue that this is not possible. Environmental degradation cannot simply be reversed and this limitation must be acknowledged to set reasonable restoration expectations. They show the effects of nutrient reductions on four Northern European coastal ecosystems, including the Gulf of Riga in the Eastern Baltic Sea, demonstrating that even with nutrient reduction, chlorophyll-a does not return to previous levels. Instead the sites show evidence of "Shifting Baselines."

The failure to meet restoration goals for the Chesapeake Bay can also be considered a "Shifting Baselines" scenario. Restoration efforts have limited further degradation of the Chesapeake and have led to improvements in some of its tributaries, but there have not been large improvements in overall ecosystem health. Accumulating forcing factors have led to a resilient but more degraded state for the Chesapeake3.

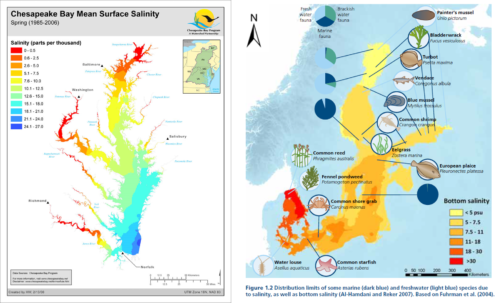

There are obvious factors that distinguish the Baltic and Chesapeake systems such as the differences in size, depth, and salinity gradient and the differences in industrial uses, including the production of crude oil, the extraction of mineral resources from the seafloor, extensive wind farms, and the elevated concentrations of radioactive material from Chernobyl fallout in the Baltic4. Yet the Baltic Sea shares many of the environmental challenges of the Chesapeake and its tributaries, including persistent organic pollutants, nutrient and sediment pollution, and unsustainable fisheries4. Both have long-term protection and restoration programs—HELCOM, founded in 1974 for the Baltic, and the Chesapeake Bay Program (CBP), founded in 19833,4.

HELCOM's operation and goals reflect the challenges of a program administered by various countries (contracting parties include Denmark, Estonia, the EU, Finland, Germany, Latvia, Lithuania, Poland, Russia and Sweden) versus the CBP's state and regional partners3,5. The CBP's ability to specifically outline outreach oriented goals such as citizen stewardship and environmental literacy likely stems from its partners all falling under the same federal government6. HELCOM, is an especially impressive example of cooperation for environmental management when considering the political climate under which it formed and the differences in economic power between the member countries.

HELCOM and the CBP both have had to adapt to survive so long with changing political, social, and economic climates. Although the CBP has not faced quite the changes HELCOM has, these changing climates still have vast impacts on management and the enforcement of policies relating to Bay health. Chesapeake environmental management in Maryland involves NGOs such as the Chesapeake Bay Foundation (CBF), government agencies like the Maryland Department of Natural Resources (DNR), scientific research organizations like the University of Maryland Center for Environmental Science (UMCES), and the watermen and public that use and depend on the Bay. With this comes a need to understand the agendas of all parties.

A decision in 2010 by former Governor of Maryland Martin O'Malley extended oyster sanctuaries to promote restoration; however, DNR recently proposed to shift the boundaries of oyster sanctuaries, decreasing the size of sanctuaries by 11% in response to pressure from current Governor Larry Hogan and dissatisfied watermen7. This same shift in political leadership also led to the recent firing of DNR's crab program manager, Brenda Davis, in response to watermen's complaints to Governor Hogan8. These decisions are in opposition to policies designed to allow species rebound and improve the health of the bay, but also highlight the difficulties of environmental management when directly related to a group's livelihood. These groups all need to be ready to work with who is in charge while also fostering better communication to avoid "us against them" mentalities.

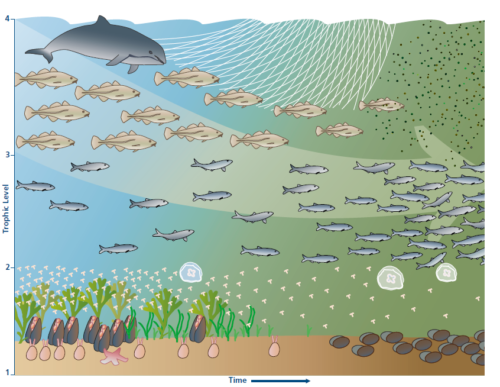

Managing inter-group conflicts and maintaining the reputation of scientists, government agencies, and NGOs depend on policy aimed at improving Bay health and limiting degradation while also setting reasonable goals for Chesapeake recovery. With long-term shifts in food web structures, increasing population, a warming climate, and high rates of relative sea-level rise in the region, returning to the Chesapeake Bay of the past is likely Neverland. Creating policies around this outlook could decrease public confidence in environmental management or could lead to the abandonment of important restoration efforts with the view that if the Bay is "unrecoverable," increasing degradation is inevitable. However, is setting goals based on past baselines and failing to reach them worse in terms of public confidence in scientists and environmental agencies?

Maybe the answer as scientists to adapt to these changing climates, literally and figuratively, is not just storytelling, but also marketing. Both HELCOM and the CBP have faced issues with budgets for monitoring3,4. Scientific marketing can address issues such as this by putting the small fraction of a budget needed for monitoring in perspective of the overall project budget or by highlighting costs saved by assuring implementations work before wasting funds on ineffective measures. Through marketing, scientists can better communicate the future benefits of current restoration even if a true return to a past state is impossible9.

References:

1. Barrie, J.M. (1911). Peter Pan and Wendy. London.

2. Duarte, C.M., D.J. Conley, J. Carstensen, and M. Sánchez-Camacho. (2009). Return to Neverland: Shifting baselines affect eutrophication restoration targets. Estuaries and Coasts 32: 29-36.

3. Boesch, D.F., and E.B. Goldman. (2009). Chesapeake Bay: USA. In Ecosystem-based management for the oceans, eds. K. McLeod, H. Leslie. Washington, D.C.: Island Press.

4. HELCOM. (2010). Ecosystem Health of the Baltic Sea 2003-2007: HELCOM Initial Holistic Assessment. Baltic Sea Environmental Proceedings 122. Helsinki: HELCOM. 64 p.

5. HELCOM. (2017). Contracting Parties. http://www.helcom.fi/about-us/contracting-parties. Accessed 27 February 2017.

6. Chesapeake Bay Program. (2014). Chesapeake Bay Watershed Agreement. http://www.chesapeakebay.net/chesapeakebaywatershedagreement. Accessed 27 February 2017.

7. Wheeler, Timothy B. "MD DNR drafts plan that would shrink state's oyster sanctuaries," Bay Journal. February, 2017. http://www.bayjournal.com/article/md_dnr_drafts_plan_that_would_shrink_states_oyster_sanctuaries

8. Kobell, Rona. "Maryland's veteran crab manager fired after watermen complain to Hogan," Bay Journal. February, 2017. http://www.bayjournal.com/article/marylands_veteran_crab_manager_fired_after_watermen_complain_to_hogan

9. Costanza, R. et al. (2014). Changes in the global value of ecosystem services. Global Environmental Change 26: 152-158.

Next Post > Ecodrought on the east side of the Pacific Northwest

Comments

-

Ginni La Rosa 9 years ago

Very well written article! We as scientists for the most part have come to terms with the concept of shifting baselines and the fact that a return to an ideal past state is impossible. But from a communication standpoint, I would find it difficult to explain this to members of the public without coming across as having an air of doom and gloom. Nevertheless there are certainly other scientific communicators who are able to do so; it will be an important skill moving forward. In regards to environmental marketing, perhaps scientists could inform the public more widely about recent estimated dollar values of ecosystem services. When it comes to bridging the language gap between science and society, money could serve as a common dialect.

-

Kavya Pradhan 9 years ago

This is really well written and does a great job of summarizing all the major points of both the discussion and our readings. I definitely agree with the need for shifting our expectations of what is possible while ensuring that we don't compromise ecosystem health. Regarding the marketing, I think we could always benefit from learning how people take in information in order to present science in the most effective way.

-

Alterra Sanchez 9 years ago

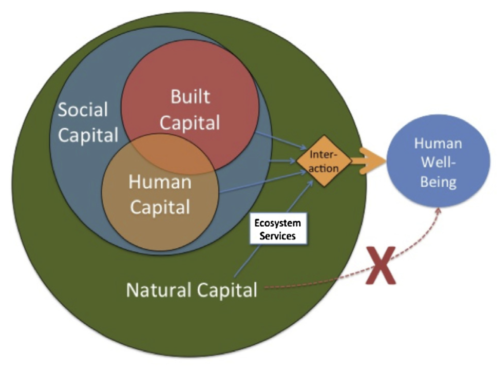

Good job Katie and Hadley! This blog wonderfully synthesizes a very complex topic and concisely describes the problems of the Chesapeake, and managing ecosystems in general in this ever warming planet, and changing economy. I especially like the last graphic, but am a little confused about why there is an X from natural capital to human well being. Is the diagram saying that we enjoy the benefits of ecosystem services indirectly, and therefore people have a harder time understanding the "connectedness" of those goods and service and our actions?

-

Jake Shaner 9 years ago

Very nice succinct comparison between the issues facing the Chesapeake and the Baltic. I'm glad you included the point made in class about scientists embracing marketing. I never considered this before and am interested to see the possible effects this might have on environmental management.