The Ohio River’s Split Personality

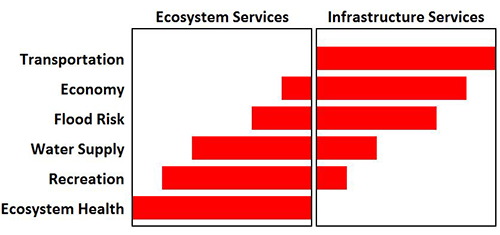

Bill Nuttle · | Science Communication |Report card goals relate to benefits provided by coexisting natural ecosystems and human-built infrastructure.

The problem is that the Ohio River is a working river. That thought occurred to me as I watched the barges glide past the window during the Ohio River report card workshop last December. A team of IAN science communicators spent two days on the banks of the Ohio River, across from Cincinnati, gathering information from experts on the Ohio and Tennessee River basins. The workshop is part of the work to develop a report card for the Mississippi River watershed. This report card will be different from others we have worked on that grade ecosystem health, like the Chesapeake Bay report card. For the Mississippi River report card, we have to figure out how to assign grades to some distinctly unnatural attributes of the river basin.

Transportation presents the biggest challenge. How does one grade a river basin on the transportation that it provides? It is easier to see how the other goals – water supply, flood risk reduction, recreation, ecosystem health, and support for the economy – each depend on the health of the ecosystem in the river basin. Watching the steady stream of barges moving past the built-up waterfront of Cincinnati brought home the fact that while transportation and the ecosystem are strongly related, the relationship is reversed. The flow of people and cargo has shaped this river just as surely as the flow of water it carries.

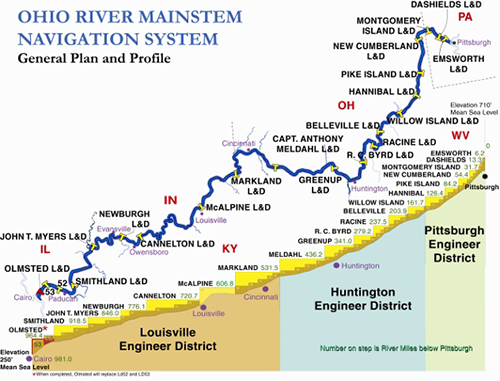

The Ohio River forms a natural transportation corridor linking the east coast and the central plains of North America, and efforts to re-engineer the river have a nearly 200-year history. That means that this river basin has been the focus of efforts to re-engineer it for a long time. Construction of the Cumberland Road, now US Route 40, began in 1811 to provide access through the Appalachian Mountains from the east-flowing Potomac River to the Ohio River. The Baltimore and Ohio Railroad (1828) and the Chesapeake and Ohio Canal (1831) were constructed for the same purpose. In 1824, Congress gave the US Army Corps of Engineers the task of altering the river channel to improve navigability. As a result, where in its natural state the Ohio River consisted of a series of pools and riffles at low flow, now an engineered system of locks and dams maintains a 9-foot deep channel for navigation at all times.

How to fit transportation into an environmental report card is related to the question of how we think people fit into the natural environment. Ecosystems include people. But, do ecosystems necessarily include everything that people do? Ecologists talk about salt marshes and seagrass beds as ecosystems, understanding that they are contained within the larger coastal ecosystem. But, does the coastal ecosystem also include cities? Likewise, does the Mississippi River ecosystem include the distinctly human habitats along its banks: the cities and the systems of flood control, water supply, and transportation infrastructure constructed to support them?

Ecosystems depend on transportation functions provided by natural processes, such as the movement of air, water, and organisms. Nutrients transported by freshwater inflow and detritus exported from coastal wetlands on the tides subsidize the productivity of coastal ecosystems. In aquatic ecosystems, many species of fish migrate long distances along rivers and streams as part of their life cycle. In the Florida Everglades, the annual cycle of wetting and drying regulates the food web by controlling the distribution of forage fish; wading birds depend on the concentration of fish as the wetlands dry down to feed newly hatched young birds. In terrestrial ecosystems, the ease with which animals can move between habitats that provide food and shelter affects what kinds and how many animals the ecosystem can support.

However, river transportation is not a benefit that the natural ecosystem provides to people; that is, transportation is not an ecosystem service. Ecologists and economists began talking about ecosystem services in the 1990s as a way to expand peoples’ awareness of the many different ways in which we rely on natural ecosystems. Services that ecosystems provide to people fall into three broad categories: provisioning services (food, fiber and other products obtained); regulating services (cleansing water and air, controlling disease and pests, etc.); and cultural services (enjoyment of nature, opportunities for recreation, etc.). There is a fourth category, supporting services that include functions ecosystems perform to maintain themselves. There is no place in these generally-recognized categories of ecosystem services for the transportation of materials carried by barges moving up and down the river.

Ecologists find it useful to draw the distinction between natural ecosystems and human-built infrastructure. Eugene Odum uses the term techno-ecosystem to refer to the human-dominated urban-industrial society (Odum 2001). The techno-ecosystem shares the defining characteristic of an ecosystem as being an interacting system of biotic and abiotic components linked together by flows of energy and materials. While the sun is the ultimate energy source for natural ecosystems, according to Odum, techno-ecosystems are distinguished by their reliance on energy from the burning of fossil fuels and nuclear power. Techno-ecosystem are also distinguished by the level of human control and by the use of materials not found in nature, materials such as concrete, steel, and plastic.

What does the split personality of the Ohio River basin mean for our report card project?

First, recognizing that natural ecosystems and techno-ecosystems are separate, interrelated systems motivates our effort to create an report card. The distinction draws attention to the ways the two systems depend on each other. In Odum’s view, the techno-ecosystem depends on the natural ecosystem as a parasite depends on its host. The relationship between parasite and host can be a sustainable one if it is also mutualistic. At a minimum, the parasite must not overburden the host. In some instances the parasite provides the host with reciprocal support. Odum argues that we need to move toward a more mutualistic relationship between our techno-ecosystem and natural ecosystems. The report card will improve knowledge of the overall status of ecosystems and infrastructure people depend on in the Mississippi River watershed.

Second, the insight that natural ecosystems coexist with techno-ecosystems in the watershed provides an answer to the question that’s been on my mind since the Ohio River workshop. Just as ecosystem services are a way of talking about the benefits people receive from natural ecosystems, we can use the term infrastructure services to refer to the benefits people receive from Odum's techno-ecosystem. Barge transportation depends almost entirely on the infrastructure installed for marine navigation; it is not an ecosystem service. The grade for navigation should reflect the condition and operation of the navigation infrastructure.

Likewise, the goal of maintaining ecosystem health refers to health of the natural ecosystems in the watershed. We should grade ecosystem health based on environmental conditions in the natural areas of the watershed. The remaining goals depend on services provided by both the natural ecosystems and human-built infrastructure to different degrees. The report card scores for these goals will combine information on the conditions in both.

Reference

Odum, E.P., 2001. The “techno-ecosystem.” Bulletin of the Ecological Society of America 82:137-138.